Chancellor of the Great War

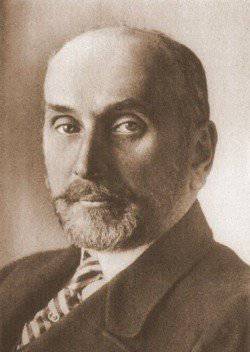

In the historiography of Russian diplomacy, strangely enough, the iron hierarchy has not developed. Who should be considered the lights of our foreign policy? Stayed in historical in memory of the people of Bestuzhev, Gorchakov, Chicherin, Gromyko ... During the First World War, at the time of making major decisions, the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia was occupied by an experienced diplomat Sergei Dmitrievich Sazonov.

In the historiography of Russian diplomacy, strangely enough, the iron hierarchy has not developed. Who should be considered the lights of our foreign policy? Stayed in historical in memory of the people of Bestuzhev, Gorchakov, Chicherin, Gromyko ... During the First World War, at the time of making major decisions, the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia was occupied by an experienced diplomat Sergei Dmitrievich Sazonov.By that time, his track record includes thirty years of diplomatic service. He did not belong to the number of ambitious chancellors who saw themselves as conductors of all Russian politics, the first among equals in the government. Such a giant was in the early years of the Seven Years' War Bestuzhev-Ryumin. Sazonov was more modest - and many considered him to be an independent protégé of P.A. Stolypin, then an agent of British influence in Eastern Europe. Kinship with Stolypin really helped Sazonov get a ministerial portfolio. Their wives were sisters. Spouse Stolypin - in maiden name Olga Borisovna Neidgardt, wife of Sazonov - Anna Borisovna Neidgardt. They are representatives of the Austrian family who have served Russia since the time of Peter the Great. In the court elite, discontent with the growth of Stolypin’s influence was growing, but even after the death of Prime Minister Sazonov remained at the head of Russian foreign policy. Sergei Dmitrievich worked with the new head of the government, Vladimir Kokovtsov, although he criticized him for not wanting to listen to the advice of professionals in their field.

In the pre-ministerial years, being in the diplomatic service, he visited both England and Italy (he worked in the Vatican for several years), and also in the new empire of the new type, the United States.

In the years of the First World Overseas Power will speak about itself in a new way. Washington will teach the lessons of political and economic expansion, will demonstrate agreement between the oligarchy and the state - and this rafting weakened European states will not be able to oppose anything. In the prewar years in the States, Sazonov discovered new rhythms of economic development far from the Old World. This experience was useful to him. Still, his appointment as minister to the diplomats of the old school was perceived not without skepticism. It was believed that Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin - the head of the government - simply “pushed” the candidacy of his relative.

In the summer of 1914, there was not a trace of Sazonov's former indecision. There were no significant fluctuations in his pre-war tactics: since the winter of 1913-14, the minister considered a big war to be inevitable and demonstrated a firm hand policy.

He seemed to be trying to prove that even without Stolypin he was able to maintain and even increase his influence. This behavior of the Minister of Foreign Affairs is also explained by trusting relations with the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich, and the respect that the Emperor had for his Minister. But you can not miss the British motive. Britain and France more than others were interested in Russia taking part in the war with all its forces, so that the German and Austrian armies would pull back the attack. Of course, it was a risky game for all participants. And Russia's breakthrough to the straits — quite real at a certain turn in the course of the war — would be a sensitive defeat for London. The British took into account such a danger, but they still dragged Russia into the war. At the same time, Sazonov, who no longer doubted the imminent outbreak of hostilities, was pushing the British towards a speedy entry into the war, towards mobilization.

In the summer of 1914, Sazonov became one of the ideologues of the mobilization that teased Germany. He convinced Nicholas II of the aggressiveness of German intentions and literally insisted on half-hidden, half-demonstrative mobilization. In fact, this was a declaration of war.

Of course, Russia entered the war not out of philanthropic considerations of the Slavic brotherhood, although outwardly it was convenient to present the situation that way. Much obliged alliance with France. And Paris with Berlin was crowded on one continent.

The second good reason is Sazonov’s old dream of the straits, a dream shared by many. Sazonov has long led secret talks on this topic with the leaders of the great and small powers.

The Slavic question remained in the third place, although it was useful in the game against Austria-Hungary and Turkey.

Negotiations with the German ambassador Pourtales became, perhaps, the most intense in Sazonov’s biography. Diplomats have almost friendly relations. More recently, Sazonov was reproached, even depending on the more experienced German. But in the summer of 1914, the Russian minister presented impracticable demands to Friedrich von Pourtales: “If Austria, realizing that the Austro-Serbian conflict has acquired a European character, will declare its readiness to exclude items that violate the sovereign rights of Serbia from its ultimatum, Russia will cease its military preparations ". Only on such conditions Russia was ready to back up. Germany could not go on this. Purtales sought to dissociate himself from the actions of Austria, and Sazonov had no doubt that Vienna was the satellite of Berlin, and nothing more.

The determined minister showed cunning and self-control, forcing the Germans to take the first aggressive step, although the pressure on Austria against Serbia was already perceived in Russia as an expression of German aggression.

In his memoirs, Sazonov insistently writes about the unpreparedness for war, but in 1914 it did not bother him ...

Almost two years Sazonov lasted at his post in the war years - until July 1916, when the decree of resignation found him on holiday in Finland. Two years full of events like a lifetime. Evaluated his activities, as usual, in every way. Radicals of all stripes Sazonov did not like: for Orthodox monarchists, he was known as a Westerner, a freemason, who fell into dependence from Germany, then from England. They wanted Russia's voice in the international choir to sound menacing and stately, and Sazonov maneuvered. Nor were he convinced liberals, not to mention socialists: after all, the minister remained a supporter of autocracy.

He becomes the most energetic of the opponents of the Minister of War Sukhomlinov, who turned almost into a general scarecrow. “At the beginning of 1915, I gave the Sovereign my view on the harmful inactivity of General Sukhomlinov in some detail. I hoped that a frankly spoken word by a person who was far from the military department and did not have any personal accounts with Sukhomlinov would induce His Majesty to be less trusting in the unfair optimism with which the reports of the minister were infused, often based on false data. Although my first attempt was unsuccessful and impressed the Tsar rather unfavorably to me, I resumed it at the first opportunity impressed by the information received from members of the State Duma, who transmitted to me about the growing indignation of the Duma commissions against Sukhomlinov. This time, the Sovereign, who loved his cheerful mood in Sukhomlinov, replied to me that he had long known that the general had many enemies and especially in the main apartment, but that he would look at all their accusations as unfounded until he saw “ black on white "proof of their justice."

Sazonov and his like-minded people, in the end, managed to overcome Sukhomlinov, but perhaps it turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory. Together with the resignation of the Minister of War began a large purge of government ranks, out of place in the war years.

Sazonov was an active opponent of the idea of the emperor becoming a commander in chief. He persuaded the emperor not to leave the capital for a long time - and, as time showed, showed political insight.

Warned about the danger of "inner turmoil." According to Sazonov’s impressions, it was on those audiences that he lost the sovereign’s trust. In those months, Sergei Dmitrievich was nurturing plans for a “government of national trust,” which would have supported the royal power. How reasonable was this idea in the critical year of the war? The question is insoluble. You can enumerate arguments for and against. Perhaps such a government would only exacerbate revolutionary sentiments, and the Cadet party, which would become an influential force, could take the path of radicalization. And - all the same February, and after him - and October.

In February 1916, speaking in the State Duma, he angrily threw into the hall: “This war is the greatest crime against humanity ever committed. Those who are guilty of it bear a terrible responsibility and are now exposed enough ”.

Later he himself was very proud of this speech, but she looked like mustard after dinner. In the “fatal moments,” Sazonov did not prevent the military flywheel from spinning, and in the winter of 1916, “hawkish” speeches lost popularity - and the minister adjusted to public opinion.

After the death of Ambassador A.K. Benkendorf British King George V asked the Russian emperor to appoint Sazonov as envoy to London. February almost caught him in London - the Petrograd events were hardly taken aback by the knowledgeable Tsarist ambassador, but he was not a participant in the conspiracy either. He did not have time to go to London: the revolution prevented. The new Minister Milyukov seemed to confirm Sazonov’s authority, but the diplomat was in no hurry to go to Britain. By the February transformation, he treated with restrained approval, quickly turned into anxiety. If in March 1917, the burden of the decision fell on his shoulders, Sazonov would hardly have considered the renunciation of the Romanovs as his goal. The next "temporary" Chancellor - "Minister-Capitalist" Tereshchenko sends Sazonov to resign. By the time he was completely disappointed in the revolution.

In the summer of 1917, the former foreign minister considered it a mistake to dismiss the Romanovs, which the generals decided on in a revolutionary storm.

The growth of radical sentiment was not just anxious, but with fury. October was perceived as an infernal evil, which he began to fight immediately. Well, already the first decrees of the new government brought to nothing the whole foreign policy of Sazonov. What are the dreams of the straits here ...

What's next? The White movement, an attempt to organize the Russian government in exile, which could become a subject of international law. Sazonov used his authority to achieve this goal, but achieved only local, temporary success. So, in 1919, he managed to obtain the authority of the Minister of Foreign Affairs from Kolchak.

Admittedly, Sazonov sincerely defended the interests of a ghostly Russia, in whose revival he believed. He flatly refused to yield to Finland, was offended when he was treated with no due respect.

And the allies did not allow anyone from the Russian politicians to divide Europe, although by that time the stability of the Soviet state was not obvious. If one imagines White's victory in 1920 or, let's fantasize, in 1922, it is unlikely that they would be treated at the level of “victorious powers”. Neither the efforts nor the old connections of Sazonov helped. When it comes to direct material gain, diplomats forget about friendship and become adamant.

Personally, Sazonov did not live in misery, although he did not make stone chambers in European capitals. I managed to write and publish memoirs in Berlin — quite ceremonious for those times. Emigration read this book not without interest - and Sergey Dmitrievich died shortly after the publication of the memoirs. In a foreign land, in Nice, when Europe was halfway from the First World to the Second ...

Information