Appetite wakes up in battle

Who better ate in the trenches of the First World War

Which soldier fights better - fed or hungry? The First World War did not give a definite answer to this important question. On the one hand, indeed, the soldiers of Germany, who eventually lost, were fed much more modest than the armies of most opponents. At the same time, during the war, it was the German troops that repeatedly inflicted crushing defeats on armies that ate better and even elegantly.

Patriotism and calories

History knows many examples when hungry and haggard people, mobilizing the strength of the spirit, defeated a well-fed and well-equipped enemy, but without passion. A soldier who understands what he is fighting for, why it is not a pity to give his life for it, can fight without a kitchen with hot meals ... Day, two, a week, even a month. But when the war drags on for years, one cannot be fed up with passion alone - forever the physiology cannot be deceived. The most ardent patriot will simply die of hunger and cold. Therefore, the governments of most war-preparing countries usually approach the issue in the same way: a soldier must be fed, and fed well, at the level of a worker engaged in heavy physical labor. What were the soldiers rations of different armies during the First World War?

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the ordinary soldier of the Russian army was given such a daily ration: 700 grams of rye bread crumbs or a kilogram of rye bread, 100 grams of cereals (in the harsh conditions of Siberia - even 200 grams), 400 grams of fresh meat or 300 grams of canned meat (marines). thus, it was necessary to deliver at least one steer, and a whole herd a year to hundreds of cattle), 20 grams of butter or lard, 17 grams of wheat flour, 6,4 grams of tea, 20 grams of sugar, 0,7 grams of pepper. Also on the day, the soldier was given about 250 grams of fresh or about 20 grams of dried vegetables (a mixture of dried cabbage, carrots, beets, turnips, onions, celery, and parsley), which were mostly in soup. Potatoes, unlike our days, even 100 years ago in Russia was not so common, although when it came to the front, it was also used to make soups.

During religious posts, meat in the Russian army was usually replaced with fish (mostly not marine, like today, but river, often in the form of dried smelt) or mushrooms (in soup), and butter - with vegetable. Grains in the ration in large volumes were added to the first courses, in particular, to soup or potato soup, of which cooked porridge. In the Russian army 100-year-old was used polbennaya, oatmeal, buckwheat, barley, millet groats. Rees, as a "fastening" product, the commissaries distributed only under the most critical conditions.

The total weight of all the food eaten by a soldier per day was close to two kilograms, the caloric content was more than 4300 kcal. That, by the way, was more satisfying than the diet of the Red and Soviet Army fighters (20 grams more for squirrels and 10 grams for fats). And for tea - so the Soviet soldier received four times less at all - just 1,5 grams per day, which was clearly not enough for three glasses of normal tea leaves, familiar to the “royal” soldier.

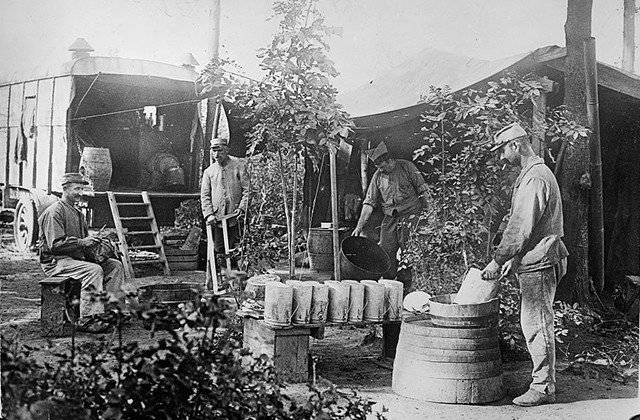

Crackers, corned beef and canned food

Under the conditions of the outbreak of war, the rations of soldiers at first were even more increased (in particular, for meat - to 615 grams per day), but a little later, as it went into a protracted phase and resources dried up, even in then still agrarian Russia, they were reduced again, and fresh meat was increasingly replaced by corned beef. Although, in general, up to the revolutionary chaos of 1917, the Russian government somehow managed to maintain the nutritional standards of the soldiers, only food quality deteriorated.

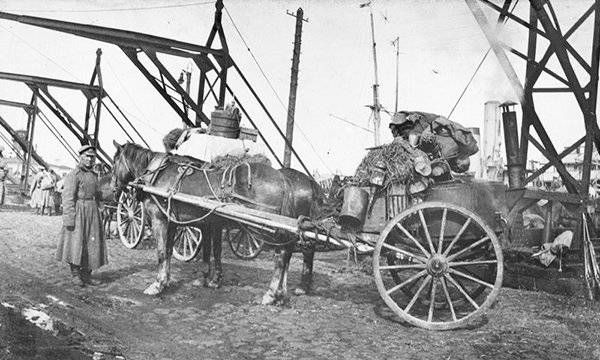

The point here was not so much the ruin of the village and the food crisis (the same Germany suffered from it many times more), as in the eternal Russian misfortune - an undeveloped network of roads along which the quartermaster had to drive bulls to the front and bring hundreds of thousands of tons to potholes flour, vegetables and canned food. In addition, the refrigeration industry was in its infancy then (cows ’carcasses, vegetables and grain had to somehow be saved from spoilage, stored and transported in colossal quantities). Therefore, situations like bringing rotten meat to the Potemkin battleship were a frequent phenomenon, and not always only because of malicious intent and theft of commissaries.

It was not easy even with soldier's bread, although in those years it was baked without eggs and butter, from only flour, salt and yeast. But in peacetime it was prepared in bakeries (in fact - in ordinary Russian ovens), located in the places of constant deployment of parts. When the troops moved to the front, it turned out that to give the soldier a kilogram loaf in the barracks was one thing, and in the open field it was quite another. The modest field kitchens could not bake a large number of loaves, remained at best (if the rear services were not “lost” at all on the way) handing out rusks to the soldiers.

The soldier rusk of the early twentieth century is not the golden rusk for tea we are used to, but, roughly speaking, dried pieces of the same simple loaf. If for a long time to eat only them - people began to get sick with vitamin deficiency and a serious disorder of the gastrointestinal system.

The harsh “rusk” life in the field conditions was somewhat brightened up with canned food. For the needs of the army, the then Russian industry has already produced several varieties in cylindrical "tin cans": "roast beef", "beef stew", "soup with meat", "peas with meat". Moreover, the quality of the “royal” stew differed to the advantageous side from the Soviet, and even more so, the current canned food - 100 years ago, only high-grade meat from the back of the carcass and shoulder blade was used for making. Also, when cooking canned food in the years of the First World, the meat was pre-fried, not extinguished (that is, it was placed in cans raw and boiled together with a can, like today).

Culinary recipe of the First World War: soldier's soup.

A bucket of water is poured into the boiler, about two kilograms of meat are thrown there, a quarter of a sauerkraut bucket. Groats (oatmeal, buckwheat or barley) are added to taste “for density”, for the same purpose, one and a half cups of flour are poured, salt, onions, pepper and bay leaf are to taste. Brewed for about three hours.

Vladimir Armeev, "Brother"

French cuisine

Despite the outflow of many workers from agriculture and food industry, developed agrarian-industrial France during the First World War managed to avoid hunger. Only some “colonial goods” were missing, and these interruptions were not systematic. A well-developed road network and the positional nature of the fighting allowed us to quickly deliver products to the front.

However, as historian Mikhail Kozhemyakin writes, “the quality of the French military food at different stages of the First World War differed significantly. In 1914 - the beginning of 1915, it clearly did not meet modern standards, but then French quartermasters caught up and even overtook foreign colleagues. Probably not a single soldier during the Great War — not even the American — ate as well as the French.

The main role here was played by the long tradition of French democracy. It was because of her, paradoxically, that France entered the war with an army that did not have centralized kitchens: it was thought that it was not good to force thousands of soldiers to do the same, to impose a military chef on them. Therefore, each platoon was handed out their sets of kitchen utensils - they said that soldiers love to eat more, what they cook from the set of products and packages from the house (they had cheeses, sausages, canned sardines, fruits, jam, sweets, biscuit). And every soldier is his own cook.

As a rule, ratatouille or another type of vegetable stew, bean soup with meat and the like were prepared as main dishes. However, the natives of each region of France sought to introduce into the field of cooking something specific of the richest recipes of their province.

But such a democratic "initiative" - romantic bonfires in the night, kettles boiling on them - turned out to be fatal in terms of positional warfare. German snipers and artillery gunners immediately began to orient themselves towards the lights of the French field kitchens, and the French army suffered at first unjustified losses because of this. The military suppliers, reluctantly, had to unify the process and also introduce mobile field kitchens and braziers, cooks, food peddlers from the near rear to the front, standard rations.

The ration of French soldiers from 1915 was of three categories: normal, reinforced (during battles) and dry (in extreme situations). The usual consisted of 750 grams of bread (or 650 grams of rusk biscuits), 400 grams of fresh beef or pork (or 300 grams of canned meat, 210 grams of corned beef, smoked meat), 30 grams of fat or fat, 50 grams of dried meat, smoked meat, 60 grams of fat or fat, 24 grams of dried meat, smoked meat, 34 grams of fat or fat, 50 grams of dried meat, smoked meat, 40 grams of fat or fat, 16 grams of dried meat, smoked meat, 12 grams of fat or fat, XNUMX grams of dried meat, smoked meat, XNUMX grams of fat or fat, XNUMX grams of dried meat, smoked meat grams of rice or dried vegetables (usually beans, peas, lentils, potato or beetroot sublimate), XNUMX grams of salt, XNUMX grams of sugar. Reinforced provided an "increase" more XNUMX grams of fresh meat, XNUMX grams of rice, XNUMX grams of sugar, XNUMX grams of coffee.

All this, in general, resembled a Russian ration, the differences consisted of coffee instead of tea (24 grams per day) and alcoholic beverages. In Russia, a half-cooker (a little more than 70 grams) of alcohol was relied upon by soldiers before the war only on holidays (10 once a year), and with the start of the war, a dry law was introduced. The French soldier, meanwhile, drank from the heart: at first, he was supposed to have 250 grams of wine a day, and by the year 1915 - a half-liter bottle (or liter of beer, cider). By the middle of the war, the rate of alcohol was increased by another one and a half times - to 750 grams of wine, so that the soldiers radiate optimism and fearlessness as much as possible. Those who wish were also not forbidden to buy wine with their own money, which is why in the trenches by the evening there were soldiers who did not bite the bast. Also in the daily ration of the French warrior was tobacco (15-20 grams), while in Russia, donators donated donations for tobacco to soldiers.

It is noteworthy that the reinforced wine ration was relied only on the French: for example, the fighters from the Russian brigade who fought on the Western front in the camp of La Curtin were given out only 250 grams of wine. And the Muslim soldiers of the French colonial troops replaced the wine with additional portions of coffee and sugar. Moreover, as the war tightened, coffee became increasingly scarce and began to be replaced by barley and chicory substitutes. Front-line soldiers compared their taste and smell with “dried goat shit”.

The rations of the French soldier consisted of 200-500 grams of biscuits, 300 grams of canned meat (they were taken from Madagascar, where they made whole production), 160 grams of rice or dried vegetables, no less than 50 grams of concentrated soup (usually chicken with macaroni or beef with vegetables or rice - two briquettes 25 grams), 48 grams of salt, 80 grams of sugar (packaged in two portions in sachets), 36 grams of coffee in compressed tablets and 125 grams of chocolate. Sukhpay was also diluted with alcohol - a half-liter bottle of rum, which the sergeant was in charge of, was given to each compartment.

French writer Henri Barbusse, who fought on World War I, described food on the front line in this way: “The main food of every day, which was to be called“ soup, ”consisted of meat with either spaghetti pasta, or rice, or beans, more or less less boiled, or with potatoes, more or less peeled, swimming in brown slush, covered with spots of hardened fat. There was no hope of getting either fresh vegetables or vitamins. ”

On the calmer sections of the front, the soldiers were more likely satisfied with the food. In February, 1916, Corporal of the 151 Line Infantry Regiment, Christian Bordechien wrote in a letter to his relatives: “During the week we twice had pea soup with corned beef, twice - sweet rice milk soup, once - beef soup with rice, once - green beans and once - vegetable stew. All this is quite edible and even tasty, but we scold the cooks so that they do not relax. ”

Instead of meat, fish could be given out, which usually caused extreme displeasure not only to mobilized Parisian gourmets - even soldiers recruited from simple peasants complained that after a salted herring they were thirsty, but it was not easy to get water at the front. After all, the surrounding area was plowed up with shells, littered with feces from a long stay at one point of whole divisions and the uncleared bodies of the dead, from which corpse poison was dripping. All this smelled of trench water, which had to filter through gauze, boil and then filter again. In order to fill the soldier's flasks with clean and fresh water, military engineers even carried out pipelines to the front, into which water was supplied by means of sea pumps. But German artillery often destroyed them too.

Army swede and galette

Against the background of the triumph of French military gastronomy and even Russian, simple but nourishing catering, and the German soldier ate more sadly and poorly. A relatively small Germany fighting on two fronts was doomed to malnutrition in a protracted war. Neither the food purchases in the neighboring neutral countries, nor the robbery of the occupied territories, nor the state monopoly on grain purchases saved.

In the first two years of the war, agricultural production in Germany was almost halved, which had a catastrophic effect on the supply of not only the civilian population (hungry “turnip” winters, the death of 760 thousands of people from malnutrition), but also the army. If before the war, the food ration in Germany averaged 3500 calories per day, in 1916-1917 it did not exceed 1500-1600 calories. This real humanitarian catastrophe was man-made - not only because of the mobilization of a large part of the German peasants into the army, but also because of the slaughter of pigs in the first year of the war as "devourers of scarce potatoes." As a result, in the 1916 year, the potatoes did not make it because of bad weather, and there was already a catastrophic lack of meat and fat.

Surrogates became widespread: rutabaga replaced potatoes, margarine - butter, saccharin - sugar, and barley or rye grains - coffee. The Germans, who happened to compare the famine in 1945 to the famine of 1917, then recalled that the First World War was harder than on the days of the collapse of the Third Reich.

Even on paper, according to standards that were observed only in the first year of the war, the daily ration of the German soldier was less than in the armies of the Entente countries: 750 grams of bread or pastry, 500 grams of lamb (or 400 grams of pork, or 375 grams of beef or 200 grams canned meat). Also, 600 grams of potatoes or other vegetables, or 60 grams of dried vegetables, 25 grams of coffee or 3 grams of tea, 20 grams of sugar, 65 grams of fat or 125 grams of cheese, pate or jam, tobacco of choice (from snuff to two cigars per day) .

German rations consisted of 250 grams of biscuits, 200 grams of meat or 170 grams of bacon, 150 grams of canned vegetables, 25 grams of coffee.

At the discretion of the commander, alcohol was also given out - a bottle of beer or a glass of wine, a large glass of brandy. In practice, commanders usually did not allow the soldiers to attach themselves to alcohol on the march, but, like the French, allowed to moderately get drunk in the trenches.

However, by the end of 1915, all the norms even of this ration existed only on paper. The soldiers were not given even bread, which was baked with the addition of swede and cellulose (ground wood). The rutabagum replaced almost all the vegetables in the ration, and in June 1916 of the year, meat began to be given out irregularly. Like the French, the Germans complained about the disgusting - dirty and poisoned with corpse poison - water near the front line. The filtered water was often not enough for people (the flask contained just 0,8 liters, and the body required up to two liters of water per day) and especially for horses, and therefore the strictest ban on drinking unboiled water was not always respected. From this were new, completely ridiculous diseases and death.

The British soldiers, who had to carry food by sea (and there were German submarines operating there) or fed food on the spot, in those countries where military operations took place (and there even the allies didn’t like to sell it themselves) were poorly fed. In total, over the years of the war, the British were able to transport to their units fighting in France and Belgium more than 3,2 million tons of food, which, despite a startling figure, was not enough.

The ration of the British soldier consisted of bread or biscuits all from 283 grams of canned meat and 170 grams of vegetables. In 1916, the norm for meat was also reduced to 170 grams (in practice, this meant that the soldier did not receive meat every day, parts put in reserve - and only on every third day and the calorie intake in 3574 calories per day ).

Like the Germans, the British also began to use supplements from turnips and turnips when baking bread - they lacked flour. Horsemeat was often used as meat (horses killed on the battlefield), and the famous English tea increasingly resembled the "taste of vegetables." True, so that the soldiers would not hurt, the British thought to indulge them with a daily portion of lemon or lime juice, and add peas in the pea soup and other semi-edible weeds growing near the front. Also, the British soldier was supposed to give out a pack of cigarettes or an ounce of tobacco per day.

Briton Harry Patch is the last veteran of the First World War who died in 2009 at the age of 111 years, so he recalled the trench life: “Once we were spoiled with plum and apple jam for tea, but the biscuits for him were doggy.” The cookie tasted so hard that we threw it away. And then it is unknown where two dogs came running from, whose owners killed the shells, began to squabble at our cookies. They fought for life and death. I thought to myself: “Well, I don’t know ... Here are two animals, they fight for their lives. And we, two highly civilized nations. What are we fighting here?”

Culinary recipe of the First World: potato soup.

A bucket of water is poured into the pot, two kilograms of meat and about half a bucket of potatoes, 100 grams of fat (about half a pack of butter) are put. For the density - half a cup of flour, 10 glasses of oatmeal or pearl barley. Parsley, celery and parsnip roots are added to taste.

Information