"Black Dutch": African arrows in the Indonesian jungle

Dutch East Indies

Despite the fact that by the XIX century the military and political power of the Netherlands was largely lost, the “country of tulips” continued its expansionist policy in Africa and especially in Asia. Since the XVI century, the attention of the Dutch navigators attracted the island of the Malay Archipelago, where the expedition went for spices, valued in gold in Europe of those times. The first Dutch expedition to Indonesia arrived in 1596 year. Gradually, Dutch trading posts were formed on the islands of the archipelago and on the Malay peninsula, from which the Netherlands began to colonize the territory of modern Indonesia.

Along the way, with the military and commercial advancement into Indonesia, the Dutch pushed the Portuguese off the islands of the Malay Archipelago, whose influence had previously included Indonesian lands. The weakened Portugal, which by this time was one of the most economically backward European countries, could not withstand the onslaught of the Netherlands, which had much greater material resources, and was eventually forced to cede most of its Indonesian colonies, leaving only East Timor behind. already in 1975, it was annexed by Indonesia, and only after more than twenty years it gained long-awaited independence.

The most active Dutch colonialists launched from 1800 year. Until this time, the Dutch East India Company carried out military and trade operations in Indonesia, but its capabilities and resources were not enough to completely conquer the archipelago, therefore the power of the Dutch colonial administration was asserted in the conquered areas of the islands of Indonesia. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French were short-lived in the control of the Dutch East Indies, then the British, who, however, chose to give it back to the Dutch in exchange for African territories colonized by the Netherlands and the Malacca peninsula.

The conquest of the Malay Archipelago by the Netherlands met with desperate resistance from the locals. First of all, by the time of the Dutch colonization, a significant part of the territory of present Indonesia already had its own state traditions, enshrined by Islam spread on the islands of the archipelago. Religion gave ideological coloring to the anti-colonial speeches of Indonesians, which were painted in the color of the holy war of Muslims against the infidel colonizers. Islam was also a rallying factor that unites numerous peoples and ethnic groups of Indonesia to resist the Dutch. Therefore, it is not surprising that in addition to local feudal lords, the Muslim clergy and religious preachers, who played a very important role in mobilizing the masses of the people against the colonialists, actively participated in the struggle against the Dutch colonization of Indonesia.

Java war

The most active resistance to the Dutch colonialists unfolded just in the most developed and with their own state tradition of the regions of Indonesia. In particular, in the west of the island of Sumatra in 1820's - 1830's. The Dutch faced the “Padri movement” under the leadership of Imam Banjol Tuanku (aka Muhammad Sahab), who shared not only anti-colonialist slogans, but also ideas of a return to “pure Islam”. 1825 to 1830 The bloody Javanese war lasted, in which the Dutch, who tried to finally conquer Java, the cradle of Indonesian statehood, were opposed by the Prince of Yogyakarta Diponegoro.

This cult hero of the Indonesian anti-colonial resistance was a representative of the side branch of the Yogyakarta Sultan dynasty and therefore could not claim the throne of the Sultan. However, among the population of Java, he enjoyed "frenzied" popularity and managed to mobilize tens of thousands of Javanese to participate in the guerrilla war against the colonialists.

As a result, the Dutch army and Indonesian soldiers employed by the Dutch authorities, primarily Ambonians, who were considered more loyal to the colonial authorities as Christians, suffered enormous losses during clashes with the partisans of Diponegoro.

The rebellious prince was defeated only with the help of betrayal and chance - the Dutch knew the route of moving the leader of the rebellious Javanese, after which it was a matter of technique to seize him. However, Diponegoro was not executed - the Dutch preferred to save his life and permanently exile to Sulawesi, rather than turn him into a martyr hero for the broad masses of the Javanese and Indonesian people. After the capture of Diponegoro by the Dutch troops under the command of General de Kok, it was possible to finally crush the actions of the rebel detachments, deprived of a single command.

During the suppression of the uprisings in Java, the Dutch colonial troops acted with particular cruelty, burning entire villages and destroying civilians in thousands. The details of the colonial policy of the Netherlands in Indonesia are quite well described in the novel “Max Havelaar” by the Dutch author Edward Decker, who wrote under the pseudonym “Multatuli”. Thanks largely to this work, the whole of Europe learned about the brutal truth of Dutch colonial politics in the second half of the 19th century.

Aceh war

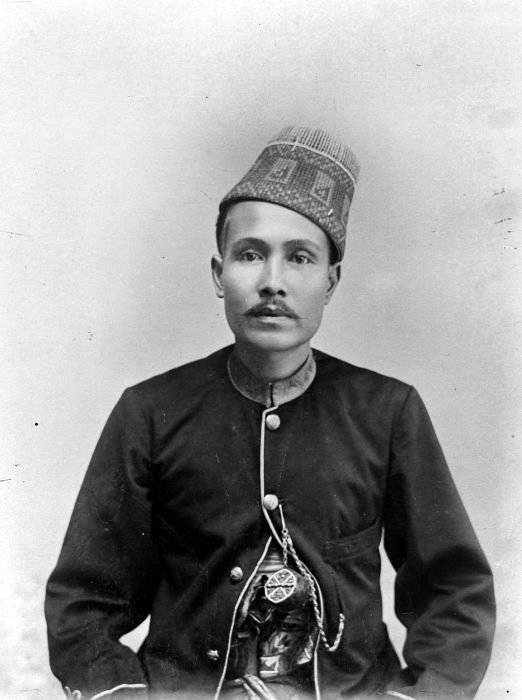

For more than thirty years, from 1873 to 1904, the residents of the Aceh Sultanate in the far west of Sumatra waged a real war against the Dutch colonialists. Due to its geographical position, Aceh has long served as a bridge between Indonesia and the Arab world. Back in 1496, a sultanate was created here, which played an important role not only in the development of the tradition of statehood on the Sumatra Peninsula, but also in the formation of Indonesian Islamic culture. Merchant ships from Arab countries arrived here, there was always a significant stratum of the Arab population, and it was from here that Islam began to spread throughout Indonesia. By the time of the Dutch conquest of Indonesia, the Sultanate of Aceh was the center of Indonesian Islam - there were many religious schools, religious education was conducted for young people.

Naturally, the population of Aceh, the most Islamized, extremely negatively related to the very fact of the colonization of the archipelago by the “infidels” and their establishment of the colonial order contrary to the laws of Islam. Moreover, Aceh had a long tradition of existence of his own state, his feudal nobility, who did not want to part with his political influence, as well as numerous Muslim preachers and scholars for whom the Dutch were nothing more than "infidel" conquerors.

Sultan Aceh Muhammad III Daud Shah, who led the anti-Holland resistance, throughout the thirty-year Aceh war sought to use any chance that could influence the policy of the Netherlands in Indonesia and force Amsterdam to abandon plans to conquer Aceh. In particular, he tried to enlist the support of the Ottoman Empire, a longtime trading partner of the Aceh Sultanate, but Great Britain and France, who had an influence on the Istanbul throne, prevented Turkey from providing military and material assistance to co-religionists from distant Indonesia. It is also known that the sultan appealed to the Russian emperor with a request to include Aceh into Russia, but this appeal did not meet with the approval of the tsarist government and Russia never acquired a protectorate in distant Sumatra.

The Aceh war continued for thirty-one years, but after the formal subjugation of Aceh in 1904, the local population carried out partisan attacks against the Dutch colonial administration and the colonial forces. It can be said that the resistance of the Acehis to the Dutch colonialists did not actually stop until the 1945 year - until the independence of Indonesia was declared. The fighting against the Dutch killed from 70 to 100 thousands of residents of the Aceh Sultanate.

The Dutch troops, occupying the territory of the state, brutally cracked down on any attempts by Acehis to fight for their independence. Thus, in response to the guerrilla actions of Achechs, the Dutch burned entire villages, near which attacks on colonial military units and transports took place. The inability to overcome the Acheh resistance led the Dutch to build up a military group of more than 50 thousand people on the territory of the sultanate, largely consisting not only of the Dutch proper - soldiers and officers, but also of mercenaries recruited by colonial troops in various countries.

As for the deepest territories of Indonesia — the islands of Borneo, Sulawesi, the West Papua region — their inclusion in the Dutch East Indies took place only in the early twentieth century, and even then the Dutch authorities practically did not control the internal territories that were difficult to reach and inhabited by warlike tribes. These territories actually lived according to their own laws, submitting to the colonial administration only formally. However, the last Dutch territories in Indonesia were also the most difficult to access. In particular, up to 1969, the Dutch controlled the province of West Papua, from where Indonesian troops were able to knock them out only twenty-five years after the independence of the country was declared.

Mercenaries from Elmina

Solving the problem of the conquest of Indonesia required the Netherlands to increase attention to the military sphere. First of all, it became obvious that the Dutch troops, recruited in the metropolis, are not able to fully perform the functions of colonizing Indonesia and maintaining colonial order on the islands. This was due both to factors of unfamiliar climate, terrain, obstructing movements and actions of the Dutch troops, and personnel shortages - an eternal companion of armies serving in overseas colonies with an unusual climate for a European and many dangers and opportunities to be killed.

The Dutch troops, who had been recruited by contract service, did not abound in those who wished to go to service in faraway Indonesia, where they could easily die and remain forever in the jungle. The Dutch East India Company has recruited mercenaries all over the world. By the way, in Indonesia at one time he served the famous French poet Arthur Rimbaud, in whose biography there is such a moment as contractual entry into the Dutch colonial troops (however, upon arrival in Java, Rimbaud successfully deserted from the colonial troops, but this is already completely different story).

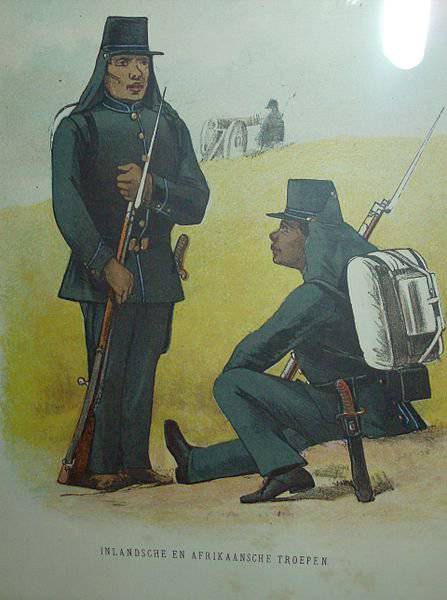

Accordingly, before the Netherlands, as well as before other European colonial powers, there was only one prospect - the creation of colonial troops, which would be staffed by cheaper in terms of funding and logistics and more accustomed to a tropical and equatorial climate hired soldiers. The Dutch command used not only the Dutch, but also the representatives of the native population, primarily people from the Molluk Islands, among whom were many Christians, and, accordingly, were considered more or less reliable soldiers as privates and corporals of the colonial troops. However, it was not possible to equip the colonial troops with Ambonians alone, especially the Dutch authorities at first did not trust the Indonesians. Therefore, it was decided to begin the formation of military units, recruited from African mercenaries recruited in the Netherlands possessions in West Africa.

Note that from 1637 to 1871. The Netherlands belonged to the so-called. Dutch Guinea, or the Dutch Gold Coast - lands on the West African coast, on the territory of modern Ghana, with its capital in Elmina (the Portuguese name is São Jorge da Mina). The Dutch were able to win this colony from the Portuguese, who formerly owned the Gold Coast, and used as one of the centers the export of slaves to the West Indies - to Dutch-owned Curaçao and the Netherlands Guiana (now Suriname). For a long time, the Dutch, along with the Portuguese, were most active in organizing the slave trade between West Africa and the islands of the West Indies, and it was Elmina who was considered the outpost of the Dutch slave trade in West Africa.

When the question arose of recruiting colonial troops capable of fighting in the equatorial climate of Indonesia, the Dutch military command recalled the aborigines of the Dutch Guinea, among whom they decided to recruit recruits to be sent to the Malay Archipelago. When embarking on the use of African soldiers, the Dutch generals believed that the latter would be more resistant to the equatorial climate and the common diseases in Indonesia, which mowed down thousands of European soldiers and officers. It was also assumed that the use of African mercenaries would reduce the casualties of the Dutch soldiers themselves.

In 1832, the first squad of 150 soldiers recruited in Elmin, including among the Afro-Dutch mulattoes, arrived in Indonesia and was stationed in South Sumatra. Contrary to the hopes of the Dutch officers on the increased adaptability of African soldiers to the local climate, black mercenaries were not resistant to Indonesian diseases and were no less sick than European soldiers. Moreover, the specific diseases of the Malay Archipelago "mowed down" even more than Europeans.

Thus, most of the African soldiers who served in Indonesia did not die on the battlefield, but died in hospitals. At the same time, it was not possible to abandon the recruitment of African soldiers, at least because of the considerable advances paid, and also because the sea route from Dutch Guinea to Indonesia was in any case shorter and cheaper than the sea route from the Netherlands to Indonesia. . Secondly, the tall growth and the unusual appearance of the Negroids for the Indonesians did their job - rumors of “black Dutch” spread across Sumatra. Thus, the corps of the colonial troops, which was called the “Black Dutch”, was born in Malay - Orang Blanda Itam.

Soldiers to serve in the African units in Indonesia, it was decided to recruit with the help of the Ashanti king who inhabited modern Ghana and then Dutch Guinea. In 1836, Major General I. Verveer, who was sent to King Ashanti’s court, concluded an agreement with the latter on the use of his subjects as soldiers, but King Ashanti singled out slaves and prisoners of war, suitable for age and physical characteristics, to the Dutch. Simultaneously with the slaves and prisoners of war, several scions of the royal house of the Ashanti were sent to the Netherlands for military education.

Despite the fact that the recruitment of soldiers on the Gold Coast provoked discontent of the British, who also claimed ownership of this territory, sending Africans to serve in the Dutch troops in Indonesia lasted until the last years of the existence of Dutch Guinea. Only from the middle of the 1850-ies was taken into account the voluntary nature of enrollment in the colonial units of the “Black Dutch”. The reason for this was the negative reaction of the British to the use of slaves by the Dutch, since the UK had banned slavery in its colonies by this time and began to fight the slave trade. Accordingly, the British had a lot of questions caused by the Dutch recruiting mercenary soldiers from King Ashanti, which was in fact the purchase of slaves. Great Britain put pressure on the Netherlands and from 1842 to 1855. recruitment of soldiers from the Dutch Guinea was not carried out. In 1855, the recruitment of African shooters began again - on a voluntary basis.

African soldiers took an active part in the Aceh war, demonstrating high combat skills in the jungle. In 1873, two African companies were moved to Aceh. Their tasks included, among other things, the defense of those Achekh villages that showed loyalty to the colonialists, supplied the latter with people, and therefore had every chance of being destroyed if they were captured by the fighters for independence. Also, African soldiers were responsible for finding and destroying or capturing the rebels in the impenetrable jungles of Sumatra.

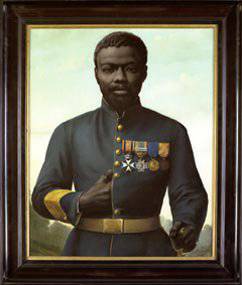

As in the colonial forces of other European states, in the units of the “Black Dutch” officers from other countries occupied the officer posts of the Netherlands and other Europeans, while Africans were filled with positions of private soldiers, corporals and sergeants. The total number of African mercenaries in the Aceh war was never great and was in other periods of military campaigns to 200 people. However, the Africans coped well with the tasks assigned to them. Thus, a number of military personnel were awarded the highest military awards of the Netherlands precisely for conducting military operations against the Aceh rebels. Jan Kooi, in particular, was awarded the highest award of the Netherlands - the Military Order of Wilhelm.

Through the participation in hostilities in the north and west of Sumatra, as well as in other regions of Indonesia, several thousand natives of West Africa passed. Moreover, if the soldiers were initially recruited among the inhabitants of Dutch Guinea - the key colony of the Netherlands on the African continent, then the situation changed. 20 April 1872 from Elmina to Java left the last ship with soldiers from the Dutch Guinea. This was due to the fact that in 1871, the Netherlands ceded the fort to Elmina and the territory of Dutch Guinea to Great Britain in exchange for recognizing their dominance in Indonesia, including in Aceh. However, since the black servicemen remembered many people in Sumatra and terrified Indonesians who were not familiar with the Negroid type, the Dutch military command tried to recruit several more parties of African soldiers.

So, in 1876-1879. Thirty African Americans recruited in the United States arrived in Indonesia. In the 1890 year, 189 natives of Liberia were also hired for military service and then sent to Indonesia. However, already in 1892, the Liberians returned to their homeland, because they were not satisfied with the conditions of service and the non-observance by the Dutch command of agreements on military labor. On the other hand, the colonial command did not feel much enthusiasm for the Liberian soldiers.

The victory of the Netherlands in the Aceh war and the further conquest of Indonesia did not mean that the use of West African soldiers in the service in the colonial troops was discontinued. Both the soldiers themselves and their descendants formed a fairly well-known Indo-African diaspora, people from whom, until the proclamation of independence of Indonesia, served in various units of the Dutch colonial army.

V.M. Van Kessel, the author of a work on the history of the “Belanda Hitam” - “Black Dutch”, describes three main stages in the functioning of the “Belanda Hitam” troops in Indonesia: the first period was a test dispatch of African troops to Sumatra in 1831-1836; the second period - the influx of the most numerous contingent from the Dutch Guinea in 1837-1841; the third period is the low level of recruitment of Africans after the 1855 year. During the third stage of the history of the “black Dutch”, their numbers steadily declined, but in the colonial troops, soldiers of African descent were still present, which is associated with the transfer of the military profession from father to son in families created by veterans “Belanda Hitam” who remained after the end of the contract the territory of Indonesia.

The proclamation of independence of Indonesia entailed the mass emigration of former African soldiers of the colonial troops and their descendants from Indo-African marriages to the Netherlands. The Africans who settled after military service in Indonesian cities and married local girls, their children and grandchildren, in 1945, realized that in sovereign Indonesia, they would most likely be attacked for their service in the colonial forces and preferred to leave the country. However, small in number Indo-African communities remain in Indonesia to the present.

Thus, in Pervoregio, where the Dutch authorities allocated land for settlement and management to veterans of the African divisions of the colonial troops, the community of Indonesian-African mestizos, whose ancestors served in the colonial troops, still remain. The descendants of African soldiers who emigrated to the Netherlands remain alien to the Dutch racially and culturally alien people, typical "migrants", and the fact that their ancestors for several generations faithfully served the interests of Amsterdam in distant Indonesia, in this case plays no role .

Information