Captain decent people. How Tomas Sankara Built a Fair Society in Burkina Faso

From the Upper Volta colony to the “Homeland of Decent People”

4 and 5 August - in stories Burkina Faso special days. First, 5 August 1960, the former French colony of Upper Volta (as it used to be called this West African country) officially gained independence. Secondly, 4 August 1983, as a result of a military coup, Thomas Sankara came to power. Thirdly, 4 August 1984, the Upper Volta received a new name - Burkina Faso, under which the state currently exists. Perhaps the Sankara rule is the most remarkable page in the modern history of this small West African country.

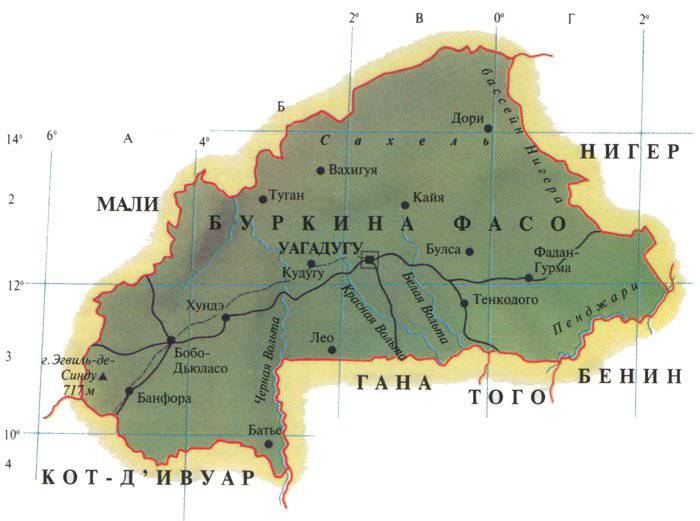

By the time of gaining state sovereignty (5 in August 1960), Upper Volta was one of the least developed economically and culturally colonies of France in West Africa. This is a typical country of the Sahel, pre-Saharan plains, with all the ensuing consequences: a dry climate, desertification of land, lack of drinking water. In addition, Upper Volta has no access to the sea - from all sides this state borders with other countries: in the north - with Mali, in the northeast and east - with Niger, in the southeast - with Benin, in the south - with Togo and Ghana, in the southwest - with Côte d'Ivoire.

The economic and strategic importance of the Upper Volta for the French colonial empire was insignificant, which influenced the size of the funds and forces invested by France in the development of this distant territory.

However, at the end of the 19th century, France, colonizing West Africa, inflicted a military defeat on the Yatenga kingdom that existed on this territory, and in 1895 it recognized French domination. Two years later, the state of Fada-Gourmet became a protectorate of France. The feudal kingdoms created by the Mosi people living here were retained by the French colonial authorities as a cover for implementing their own policies. Over the 65 years of the earth, named for the Upper Volta River originating the Volta River, belonged to France.

The liberation from colonial rule did not bring Upper Volta either economic prosperity or political stability. The country's first president, Maurice Yameogo, the former minister of agriculture, interior and prime minister of colonial autonomy, managed to rule six years - from 1960 to 1966. Nothing remarkable, except as a ban on all political parties with the exception of the only ruling, his presidency was not noted. The economy did not develop, the people were impoverished, discontent grew with the policy of the president, who was in no hurry to turn Upper Volta into a truly independent state.

Then came the era of military coups. Maurice Yameogo was overthrown by the colonel (later - brigadier general) Sangule Lamizana - the creator of the armed forces of the independent Upper Volta. His presidency lasted much longer - 14 years, from 1966 to 1980. However, the general failed to restore order in the country's economy. Serious droughts fell on his reign with the subsequent crop failure and the impoverishment of the agricultural population of Upper Volta. In 1980, the military intelligence chief, General Saie Zerbo, overthrew President Lamizanu. He abolished the country's constitution and transferred the full authority of the Military Council. However, the dictatorship of the former colonial rifleman, the French paratrooper and the voltaic officer did not last long - after two years, the military doctor captain Jean Baptiste Oedraogo headed the next putsch of the voltaic officers and overthrew Zerbo. The reign of Ouedraogo continued even less - just a year, until 4 August 1983, he was overthrown by his own prime minister, captain of paratroopers Thomas Sankar.

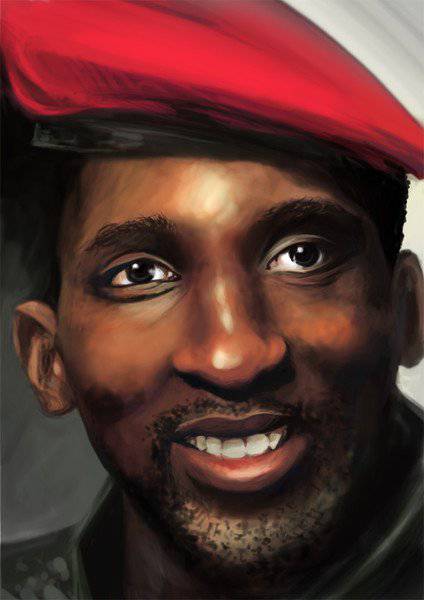

Captain with guitar

Thomas Sankara was unusually popular in the army, and then among the majority of the population of Upper Volta. He was born December 21 1949 of the year and did not belong to the traditional elite of the Voltaic society due to its mixed origins. Thomas Sambo's father Joseph Sankara (1919-2006) by nationality was Mosi - a representative of the dominant ethnic group of the country, but the mother, Margarita Sankara, came from the Fulbe people. Thus, by the fact of birth, Thomas Sankara became “silmi-mosi” - an inferior mosi, metis. Nevertheless, he managed to get an education and make a military career. The reason for this is the biography of his father. Sambo Joseph Sankara was a soldier of the French colonial troops and gendarmerie and even participated in the Second World War.

Father and mother insisted that Thomas become a Catholic priest - this way seemed more acceptable and respected to parents than military or police service. However, Sankara decided to follow in the footsteps of his father, and at the age of 19 years, in 1968, he entered military service. A guy with a good school education and obvious abilities was noticed and sent to study in Madagascar in 1969 year. There, in the city of Antsirabe, there was an officer school, which Sankara finished three years later - in 1972. It was during his studies in Madagascar that a young Voltai soldier became interested in revolutionary and socialist ideas, including Marxism and the concepts of “African socialism” that were common at that time. Returning to his homeland, Sankara began service in the elite part of the paratroopers. In 1974, he took part in the border war with Mali, and in 1976, the capable officer was entrusted to lead the training center of the Volta special forces in the city of Pau.

By the way, during the years of military service, the lieutenant, and then captain Sankara, was known among the army as not only a man of left political views, but also an "advanced" guy, a connoisseur of modern culture. He drove a motorcycle through the night capital of Ouagadougou and even played guitar in the jazz band Tout-à-Coup Jazz. During the army service in the parachute units, Sankara met several young officers who also held radical views and wanted changes in the political and economic life of their home country. These were Henri Zongo, Blaise Compaore, and Jean-Baptiste Boukari Lingani. Together with them, Sankara created the first revolutionary organization, the Group of Communist Officers.

Although Sankara was extremely dissatisfied with the regime of General Zerbo, he was still appointed Secretary of State for information in 1981. True, he soon resigned, but the military doctor Jean-Baptiste Oedraogo, who overthrew Zerbo, appointed Sankara, who had gained popularity not only among officers and soldiers, but also in the country as a whole, as Prime Minister of Upper Volta. It would seem that the young and revolutionary captain paratrooper received excellent opportunities to realize his socialist aspirations, but ... in 1983, the son of French President Mitterrand, Jean-Christophe, who served as adviser to the President of France on African affairs, visited Upper Volta. It was he who frightened Uedraogo with the possible consequences of the appointment of Sankara's “leftist” as the head of the Voltai government. Frightened Oedraogo, who was essentially an ordinary pro-Western liberal, immediately took action - not only dismissed Sankara from his post as prime minister, but also arrested him and his closest associates, Henri Zongo and Boukari Lingani.

August 4 revolution

The arrest of Sankara caused ferment in military circles. Many junior officers and soldiers of the Voltai army, already dissatisfied with the policies of President Ouedray, expressed readiness to free their idol and overthrow the Ouedray regime. Ultimately, a detachment of military personnel under the command of Captain Blaise Compaore, the fourth member of the “Group of Communist Officers” who remained at large, freed Sankara and overthrew the Ouedroyi government. 4 August 1983 was a thirty-four year old captain Sankara who came to power in Upper Volta and was proclaimed chairman of the National Revolution Council.

From the very beginning, Sankara’s activity as a de facto head of state differed from the behavior of other African military leaders who came to power in a similar way. Thomas Sankara did not arrogate to himself the rank of general, hung with orders, run his hand into the state treasury and add to key positions of relatives or tribesmen. From the first days of government, he made it clear that he was an idealist, for whom social justice and the development of his own country are values of the highest order. Stories about the poorest president have been repeatedly retold in a wide variety of media, so it hardly makes sense to bring them here in its entirety. It suffices to mention that Sankara, unlike the overwhelming majority of heads of state, did not make a fortune at all. Even as head of state, he refused the presidential salary, transferring it to the fund to help orphans, and he lived on a modest salary, put to him as a captain of the armed forces. An old Peugeot, bicycles, three guitars and a fridge with a broken freezer — these are all the belongings of a typical “guy-guitarist” from Ouagadougou, having been the fate of the West African state for several years.

Sankara's asceticism, his unpretentiousness in everyday life were not fake. Indeed, this smiling African was a disinterested and altruist. It is possible that during several years of his revolutionary leadership he made certain mistakes, excesses, but no one could ever reproach him with this - that he was guided by the interests of his own advantage or a thirst for power. Demanding of himself, Sankara demanded a lot from people employed in public service.

In particular, immediately after coming to power, he transplanted all government officials from Mercedes cars to cheap Renault, canceled personal driver posts for all officials. Negligent civil servants were sent for a couple of months for re-education on agricultural plantations. Even the World Bank, an organization suspicious of which only a madman can sympathize with ideas of social justice, admitted that in three years of leadership of Upper Volta, Sankara managed to virtually eliminate corruption in the country. For the African state it was a fantastic success, almost nonsense. Indeed, at this very time, the rulers of the neighboring countries plundered the national wealth of their homeland, organized the genocide of foreign tribesmen, bought luxury villas in the United States and Europe.

4 August 1984, the anniversary of the revolution, on the initiative of Sankara Upper Volta received a new name - Burkina Faso. This phrase encompasses the two most common languages in the country - moor (mosi) and diola. In the language of the sea, “Burkina” means “Honest People” (or “Worthy People”), in the language of the dioule “Faso” - “Motherland”. Thus, the former French colony, named for the Volta River, became the homeland of decent people. On the emblem of Burkina Faso, a hoe and a Kalashnikov assault rifle, symbols of agricultural labor and the defense of their country, crossed. Under the hoe and machine gun there was an inscription "Homeland or death, we will win."

Sankara set about reforming the very foundations of the social and political structure of Burkinian society. In the first place, on the model of Cuba, whose experience Sankara admired, the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution were organized. It seemed that these committees would assume the functions of not only the political organization of the Burkini people and lower administrative units, but also the general arming of the people.

While pursuing a revolutionary and essentially socialist policy, Thomas Sankara, at the same time, did not try to blindly copy the external attributes of the Soviet political system, which many African leaders sinned of "socialist orientation." One can hardly call him a Marxist-Leninist in the sense that the word was invested in the Soviet Union. Rather, the young officer from Burkina Faso was a supporter of the original political concept, adapting socialist ideals to the African folk traditions of social organization, economic and cultural living conditions on the African continent and specifically to Burkina Faso.

The concept of endogenous development - self-reliance

Thomas Sankara was inspired by the concept of endogenous development, that is, social, economic, political and sociocultural modernization of society based on its internal potential, its own resources and historical experience. One of the developers of this concept was the Burkinian professor-historian and philosopher Joseph Ki Zerbo. Within the framework of the concept of endogenous development, the role of the “creator of history” was assigned to the people. People were called to become active participants and authors of transformations. However, the concept of self-reliance did not mean isolationism in the spirit of the Juche idea. On the contrary, Sankara was ready to learn any positive experience of other societies, provided it adapted to the conditions of life in Burkina Faso.

The following key principles formed the basis of the policy of Thomas Sankar: self-reliance; mass participation of citizens in political life; the emancipation of women and their inclusion in the political process; transformation of the state into an instrument of social and economic transformations. The first national development plan, from October 1984 to December 1985, was adopted through the participation of residents of all localities in the country, with the financing of the plan for 100% from public funds - from 1985 to 1988. Burkina Faso did not receive any financial assistance from either France or the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund.

Sankara sharply criticized international financial organizations and rejected any form of cooperation with them, rightly regarding the activities of the World Bank and the IMF on the African continent as neo-colonialist, contributing to the economic enslavement and preservation of the backwardness of the sovereign states of Africa. By the way, Sankara was extremely negative about the idea of humanitarian assistance to developing countries, arguing that the latter only reinforces their further backwardness and teaches the parasitic existence of “professional beggars”, beneficial to the West, which seeks to continue the colonial policy of impeding the true development of sovereign states.

Thomas Sankara believed that the scientific, technological and economic possibilities of modern humanity can significantly facilitate the lives of billions of disadvantaged people on Earth. However, the predatory appetites of the world financial elite, the leaders of the major powers of the world, impede genuine social progress. Vincent Ouattara in an article on Thomas Sankar, stresses that he rejected any possibility of compromise with the neo-colonialist elites of the West, including he refused to participate in the Franco-African summit. (Ouattara V. Thomas Sankara: the revolutionary vision of Africa. Original: "Thomas Sankara: le révolutionnaire visionnaire de l'Afrique" de Vincent Ouattara.

During the year, 85% of assigned tasks were implemented, including the construction of 250 reservoirs and the drilling of 3000 wells. Solving the problem of water supply to Burkinian villages became one of the priority tasks, since Burkina Faso experienced more and more inconveniences every year due to the gradual onset of the Sahara. Desertification is a headache for the Sahel countries. In Burkina Faso, this was accompanied by a lack of access to the sea and the possibility of using desalinated water, as well as the drying up of river beds during the dry season. As a result, the country's agriculture suffered greatly, which led to crop failure, famine, and the mass exodus of peasants from villages to cities, with the subsequent formation of a large stratum of lumpen settled in urban slums. Therefore, the national project “Construction of wells” occupied such an important place in the modernization strategy of Sankara. It is indicative that, thanks to the efforts of the Sankaristic leadership, the water supply to Burkini villages and the increase in agricultural productivity have been greatly improved.

Burkina Faso achieved significant success during the years of Sankara’s rule and in the field of health care. The “Battle for Health” campaign was announced, as a result of which 2,5 of a million children were vaccinated against infectious diseases. The first among African leaders, Thomas Sankara, acknowledged the presence of AIDS and the need for its prevention. The infant mortality rates for several years of Sankara's rule have dropped from 280 children to 1000 (the world's highest rates) to 145 to 1000. Serious assistance in reforming the health care system in Burkina Faso was provided by Cuban doctors and medical assistants.

At the same time, Sankara proceeded to reform the education system. The course was taken to eradicate illiteracy, which was a serious problem in Burkina Faso. In accordance with the universal school education program, schoolchildren were trained in nine national languages used by peoples living in Burkina Faso.

Finding your own path of development has always been relevant for countries that do not belong to Western European civilization. Most of them were imposed on modernization models that completely ignored the civilizational specifics of the same African continent and were unsuitable for this reason for practical implementation in African states. At the same time, reliance on domestic resources also meant a preferential refusal of foreign lending and the dominance of imported goods in the domestic market. “Imported rice, maize and millet are imperialism,” said Sankara. As a result of the goal of self-sufficiency in the country with food, Sankara managed to significantly modernize the Burkini agricultural sector in a relatively short time, primarily through the redistribution of land, assistance in land reclamation and supply of fertilizers to peasant farms.

The emancipation of women, previously oppressed and deprived of the practical possibility of participating in the social and political life of Burkina’s society, has also become one of the priority tasks of the social revolution in the country. As in the period of the Stalinist industrialization of the USSR, under the conditions of solving the problems of the rapid economic development of Burkina Faso, it would be impermissible folly to preserve the alienation of women from public life, thereby reducing the number of human resources involved in revolutionary politics. Moreover, in Burkina Faso, as in many other countries in West Africa, which were experiencing strong Islamic influence, women occupied a degraded position in society. Sankara prohibited the formerly common practice of female circumcision, forced early marriage, polygamy, and also tried in every way to attract women to work and even to military service. In the armed forces of Burkina Faso, a special women's battalion was even created during the years of Sankara’s rule.

It is noteworthy that an important place in the modernization strategy of Sankara was occupied by the issues of solving environmental problems facing Burkina Faso. Unlike the leaders of many other African countries, for whom nature and natural resources were only means of obtaining profit, mercilessly exploited and completely unprotected, Sankara carried out truly revolutionary measures in the field of environmental protection. First of all, a massive planting of trees was organized - the groves and forests were supposed to become a “living barrier” against the Sahara, to prevent desertification of land and the ensuing impoverishment of the peasant masses of the Sahel. All the layers and ages of the Burkini population were mobilized for planting trees, in fact planting trees was timed to virtually every significant event.

According to researcher Moussa Dembele, Sankara’s policy was the clearest attempt at democratization and social liberation on the African continent after decolonization. Sankara, according to Dembele, acted as the author of a genuine development paradigm for African societies, ahead of his time and entering history as the creator of an amazing experiment (Moussa Dembele. Thomas Sankara: an endogenous approach to development, 4 report of August 2013 on the 30th anniversary of the rise to power of Thomas Sankara Original: Demba Moussa Dembélé. Thomas Sankara: An Endogenous Approach to Development (Pambazuka News, 2013-10-23, Issue 651).

Sankara, Castro, Gaddafi

In foreign policy, Thomas Sankara, as it should have been supposed, adhered to a clear anti-imperialistic line. He was guided by the development of relations with the countries of socialist orientation. In particular, in 1987, Burkina Faso was visited by Fidel Castro himself - the legendary leader of the Cuban revolution. Cuba has greatly helped Burkina Faso in reforming the health care system and organizing the fight against serious infections, which before Sankara came to power, were a real threat to the life of the country's population. On the other hand, Sankara himself admired the Cuban revolution, the personalities of Castro and Che Guevara, clearly sympathizing with him more than the Soviet regime.

However, Thomas Sankara visited the Soviet Union. But, not refusing to cooperate with the Soviet state, unlike many other African leaders, he did not declare himself a Marxist-Leninist Soviet position and preferred to keep somewhat autonomous, with "self-reliance."

But the closest relations were connected by the Burkinian leader with the head of neighboring Ghana, Jerry Rawlings. Rawlings, like Sankara, was a young officer, not just a paratrooper, but a pilot who came to power as a result of the overthrow of the rotten regime of corrupt generals. In addition, he was distinguished by unpretentiousness and underlined simplicity in everyday life - he even lived separately from his family in the barracks, emphasizing his status as a soldier.

Rawlings and Sankara shared similar ideas for the future of the African continent - like hot patriots of their countries, they saw them free from the influence of foreign capital and democratically organized. Democracy was not the European-American parliamentarism, imposed on former colonies from Washington, Paris or London, but “democracy”, which consists in increasing the real participation of the masses in managing state and public life through popular committees, revolutionary committees and other structures of self-organization of the population.

The difficult question is the relationship of Thomas Sankara with the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. It is known that Gaddafi supported many revolutionary and anti-imperialist movements throughout the world - starting with the Irish Republican Army and ending with the Palestinian resistance movement. The leader of the Libyan Jamahiriya paid special attention to African revolutionaries.

The story of the relationship between Thomas Sankara and Muammar Gaddafi - the much more famous revolutionary, the “third way” theorist and pan-Africanist - began in 1981, when Sankara was appointed secretary of state for information under the ruling regime of Colonel Sei Zerbo. It was then that Libya opened its embassy in Ouagadougou, and after Sankara was appointed prime minister in 1983, after Jean Battista Oedraogo came to power, the relations of the two states only got stronger. Not without the support of Gaddafi and Ghanaian leader Jerry Rawlings, Sankara managed power in his own hands. Gaddafi’s visit to Ouagadougou in October 1985 caused a sharply negative reaction from the Western powers, who saw this as an encroachment on their own interests in West Africa.

However, in addition to revolutionary solidarity, Gaddafi pursued far more pragmatic interests of strengthening Libyan influence in West Africa, including economic. Perhaps it was Sankara’s awareness of this fact that led to a gradual deterioration in the relations between the two leaders and prompted Gaddafi to support Sankara’s political rivals. It is likely that Muammar and humanly felt jealous of the young and worthy leader of Burkina Faso, gaining popularity not only in his own country, but also abroad. Over time, Sankara became the favorite of the masses of the whole West Africa, and this could not but alarm Gaddafi, who wanted to see himself as a revolutionary leader and idol of African peoples.

Aguser war

A serious drawback of Sankara’s policy was the conflict with neighboring Mali that followed in 1985. The reason for the conflict was the controversy around the mineral-rich Agashersky strip on the border of both states. Mali has long claimed this territory. Actually, the first combat experience of the Voltai army created on November 21 of 1961, November 1974, is connected with it. Back in 1983, there was a brief conflict with Mali, in which lieutenants Thomas Sankara and Jean Baptiste Lingani, future leaders of the XNUMX revolution, participated as officers. This short-term conflict with Mali was averted by the intervention of the presidents of Guinea and Togo, Ahmad Sekou Toure and Gnassingbe Eyadema, as mediators. However, the fighting gave the opportunity to advance and gain prestige in the army and society a number of junior officers of the Voltai army, who distinguished themselves during battles with their superior enemy.

Re-conflict broke out in the 1985 year. When a population census was conducted in Burkina Faso, Burkina census takers accidentally crossed the Malian border and entered the nomad-Fulbe camp. In response, Mali accused Burkina Faso of violating its territorial integrity. 25 December 1985 of the Year of the Agusher War began, which lasted five days. During this time, the Malian troops managed to push back the Burkinian army and occupy the territory of several villages. At the same time about three hundred people died. The war stirred up the countries of West and North Africa. Libya and Nigeria intervened, trying to take on the role of intermediaries, but they did not manage to stop the bloodshed. More successful were the efforts of Côte d'Ivoire’s President, Félix Houphouet-Boigny. 30 December, the parties ceased hostilities.

The war with Mali revealed significant shortcomings in Sankara’s military policy. The president of decent people, conducting his social reforms, underestimated the processes taking place in the country's armed forces. Colonel Charles Ouattara Lona wrote an article entitled “The Need for Military Reform”, in which, as a soldier and historian, he assessed the policy of Sankara in the military sphere (C. Ouattara Lona. The need for military reform. Original: Colonel Ouattara Lona Charles. De la nécessité de réformer l'armée L'Observateur Lundi, 03 Septembre 2012).

Thomas Sankara sought to revolutionize the country's defense system, relying on the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. Considering that “a soldier without political education is a potential criminal,” Sankara sought to democratize the control system of the armed forces and at the same time to political enlightenment of soldiers, non-commissioned officers and officers. The committees for the defense of the revolution were to organize the general arming of the people, and the people's militia, the People’s National Service (SERNAPO), should supplement the army, gradually replacing it with itself. During the struggle for power, Sankara eliminated many high-ranking and experienced officers of the old Voltaic army, who held “right-wing” and pro-Western views. Part of the survivors of repression, but not agree with the policy of Sankara, was forced to emigrate. The weakening of the armed forces significantly complicated the situation of Burkina Faso during the next border conflict with Mali in 1985.

The killing of Sankara and the return of neo-colonialism

At the same time, Sankara’s social policy caused considerable discontent among a part of the country's officer corps. Many officers, who began serving before Sankara came to power, were not pleased with the minimization of the cost of maintaining civil servants and the attempt to transfer the defense and security functions to the revolutionary committees. Dissatisfaction with Sankara's course penetrated his inner circle as well. But the main role in the formation of antisankrist sentiments was played by the policies of a number of foreign states.

First of all, the Sankara regime was extremely dissatisfied with Western countries, especially the former metropolis - France and the United States of America, who were also concerned about the success of the "self-reliance" policy and the refusal of the imposed help of US-controlled credit organizations. Under the patronage of France, there was even a conference of countries that were neighbors of Burkina Faso, which adopted an appeal to Sankara demanding an end to social policy. On the other hand, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, influential in West Africa, was increasingly cool towards Sankara’s policy. The latter, like the countries of the West, was not satisfied with the excessive independence of the Burkini leader, his course toward "own strength" and opposition to attempts to subordinate the country's economy to foreign influence.

Muammar Gaddafi began to pay more and more attention to Sankara's closest associate since his participation in the “Group of Communist Officers” - captain Blaise Compaore. In the government of Sankara, Compaore served as Minister of Justice. Although this man also began as a patriot and revolutionary, he seemed more compliant and compliant. In other words, it was always possible to agree with him. Compaore and satisfied the West, including France. Ultimately, Blaise Compaore led the conspiracy to overthrow the “captain of decent people.”

One of the advisers to Compaore on the issue of organizing an armed rebellion was the Liberian warlord Charles Taylor. Subsequently, this man as a result of the civil war in Liberia managed to come to power and establish a bloody dictatorship, but today he is a prisoner of the Hague international prison. At the Taylor trial, his closest associate, Prince Johnson, confirmed that it was Taylor who was the author of the plan to overthrow Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso.

By the way, the Liberian Taylor and the Minister of Justice of Burkina Faso Compaore were introduced to none other than the Libyan Jamahiriya leader Muammar Gaddafi. In an effort to extend his influence over Liberia and Sierra Leone with their diamond mines, Gaddafi relied on Charles Taylor, but the latter needed the support of other West African countries in the event of the start of a full-scale civil war in Liberia. Blaise Compaore promised to give such support, but for this it was necessary to ensure his coming to power in Burkina Faso. Thomas Sankara, who did not initially object to helping Taylor, spoke out against the training of Liberian militants in Burkina Faso. Accordingly, Taylor had strong motives for complicity in the overthrow of Sankara and the seizure of power by Blaise Compaore.

Bruno Joffre in his article “What do we know about the murder of Sankar?” Does not deny the likely involvement of not only Compaor and Taylor with the support of Gaddafi, but also of the West, primarily French and American special services. In the end, Taylor himself began a political career with the help of the CIA, and the United States could not arrange the policy of Sankara by definition (Joffre B. What do we know about Sankara's murder? Original: "Que sait-on sur l'assassinat de Sankara?" de Bruno Jaffré).

October 15 1987, Thomas Sankara arrived at the meeting of the National Revolutionary Council for a meeting with his supporters. At that moment they were attacked by armed men. These were the Burkinian special forces, commanded by Gilbert Diedendere, who headed the special forces training center in the city of Pau - the very one who was once headed by Sankara himself.

The thirty-eight-year-old captain Thomas Sankara and twelve of his comrades were shot and buried in a mass grave. The wife and two children of the murdered revolutionary leader of Burkina Faso were forced to flee the country. There is information that at the last moment his friend, the leader of Ghana and a no less worthy revolutionary, Jerry Rawlings, learned about the conspiracy being prepared against Thomas Sankara. The plane was already ready for departure with Ghanaian special forces who were ready to fly to Ouagadougou to defend the “captain of decent people,” but it turned out too late ...

Blaise Compaore came to power - a man who committed one of the greatest sins: betrayal and killing a friend. Naturally, the first thing Compaore, who verbally declared himself the heir to the revolutionary course, began to wind down all the achievements of the four-year rule of Thomas Sankara. First of all, the nationalization of the country's enterprises was abolished, access to foreign capital was opened.

Compaore also proceeded to the return of privileges and high salaries to officials, senior officers of the army and police, on which he planned to rely on his board. With funds that Sankara collected for a special fund for the improvement of the slums of the capital of Ouagadougou, the new president bought himself a private jet. The reaction of the West was not long in coming. France and the United States gladly acknowledged the new president of Burkina Faso, fully satisfying their interests in West Africa.

Burkina Faso was granted an IMF loan of 67 million dollars, although Sankara at one time categorically denied the need to use loans from foreign financial institutions. Gradually, all the gains of the social experiment undertaken by Sankara are a thing of the past, and Burkina Faso has become a typical African country with total poverty of the population, lack of social programs, completely subordinated to foreign companies by the economy. By the way, Blaise Compaore remains the president of the country for the last 27 years, but such a long period of being in power does not bother his French and American friends - "defenders of democracy."

Information