Kosovo field experiments

Banned Albanian language, King Zog I and Milosevic's speech on the Kosovo field, the “Russian Planet” reminds of one of the longest ethnic conflicts in Europe

The events in Ukraine have been repeatedly compared with the 1990 conflict in Yugoslavia. This was most clearly manifested in the situation around the Crimea, it was directly compared with Kosovo. This was done by President Vladimir Putin and activists, both in Russia and in Ukraine.

From the end of the 12th century until the battle of Kosovo in 1389, the region was the center of Serbian culture and politics. The churches and monasteries that have survived since then do not cease to be part of the national stories a period of higher cultural development, after which centuries-old stagnation came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Although ethnic Albanians also suffered from the oppression of Istanbul, their language was not taught in schools, unlike Serbian. And the Serbian church had sufficient autonomy. But otherwise, Albanians were more comfortable living in an Islamic state. As an ethnic minority since the time the Balkans occupied the Slavic tribes, Albanians slowly converted to Islam, freeing themselves from taxes and gaining access to public service.

The final spread of Sunni Islam among the Albanians falls on the 17th century, although among the Albanians there were even families of crypto-Catholics who called themselves Muslims. As repeatedly emphasized by the cultural heroes of the Albanian ethnos, the conflict never had any religious content and was originally ethnic.

“Albanian Renaissance” is the common name among the Albanians for the cultural ascent of the second half of the 19th century, and the accompanying struggle for independence was stimulated by weakening the position of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and strengthening the position of the Orthodox states, alien to the living environment for Muslim Albanians, whose main claim to the Ottoman regime was a language policy. There was a choice - either to become a minority in the state of the Serbs, or to create their own national state. At the same time, Kosovo as a region of residence for ethnic Albanians was historically important for the Serbs. In the year 1912, after independence was gained by Albania, the issue of borders was not yet fully resolved. While representatives of the Albanian diasporas in the territories of Serbia and Montenegro were convincing diplomats of the great powers in London, the Serbian authorities enthusiastically cleaned Kosovo from ethnic Albanians. Under the terms of the London World 1913, half of the ethnic Albanians in the somehow overlapped Balkans found themselves beyond the borders of the nation state.

During the First World War, Kosovo was occupied by Austrian and Bulgarian troops, the Albanians were on both sides of the conflict, but the Serbs considered them to cooperate with the occupiers.

Kosovo became part of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (since 1929, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), and for the new authorities it was necessary to raise the percentage ratio of Serbs to Albanians. Land was confiscated from them, and the Serbs who were resettled were given privileges. Regarding the language, Yugoslavia continued the policy of the Turkish authorities: schools with Serbian language were provided for Albanians. By the beginning of the 1930s, there were no Albanian schools or print publications in Albanian in the country. The government of Yugoslavia believed that Albanians as an ethnic minority did not exist - they were simply Albanian-speaking Serbs who were not subject to international agreement on the protection of minority rights.

At the same time, the conflict between Albanians and Serb migrants became so large that the deportation of 200 thousands of Kosovo Albanians to Turkey was discussed.

The situation in Kosovo filed with the League of Nations claimed that during the 1919 – 1921 period, Serbian forces killed 12 370 people, put 22 110 people behind bars, and burned more than six thousand houses of ethnic Albanians. Gradually, the uprising was crushed, and Ahmed Zogolli, who became an Albanian monarch named Zog I in 1928, helped the Yugoslav authorities with his leadership - the Kosovo National Defense Committee, located in Albania.

In 1941, German troops entered Kosovo and the region was transferred to the Great Albania, controlled by fascist Italy. For the first time in the history, Albanian language became the official language of public service and education in Kosovo, and all Albanians became citizens of a single national state, even if it was a conditional one. Until the end of the war, tens of thousands of Orthodox Serb families were killed or expelled from Kosovo. Under the new Fascist leadership, the task was to create an ethnically pure Kosovo. In the cleansing took part as the local population, armed with Italian weapons, as well as the "black-peaked" parts, created earlier in the puppet Albania in the Italian style. Since at that time the national sovereignty of the Albanians was lost, the purpose of such cleansings could only be revenge.

Even in the conditions of the organization of resistance to the Italian occupation, hostility towards the Serbs played a decisive role: the Albanian partisans-nationalists from the Bally Kombetar organization insisted on the unification of Kosovo and Albania. Therefore, from the proclamation of the struggle against the German and Italian invaders, they quickly turned to collaborationism, right up to open clashes with the Yugoslav communist guerrillas and actions directed against the Serbian population of Kosovo.

If, after the first wave of purges, by the end of 1941, not a single Serb village populated during the “colonization” period remained in Kosovo, the second wave of violence was already directed against the indigenous Serb population, to which the majority of Albanians were traditionally tolerant.

The outcome of the war did not significantly affect the conflict in Kosovo: Tito, his Yugoslav liberation army, with the assistance of the already liberated and communist Albania, severely suppressed the last Albanian guerrilla organizations in the province. After the break in Tito’s relationship with the ruler of Albania, Enver Hoxhoi, in 1948, Kosovo’s Albanians became “traitors” in the eyes of the Serbs. In addition, the region was faced with an economic crisis, first the remaining Serbs left Kosovo, then the Albanians.

The Tito government called Albanians living in Yugoslavia "Turks" in official documents. By agreement with Ankara, about a hundred thousand people left Kosovo to Turkey for the period from the end of the war to the 1960-s. The figure seems too high, but in Yugoslavia the Albanian minority was the leader in terms of fertility, thanks to its special clan organization and traditional family values.

A short period of fragile peace in the region began during the period of the new constitutions of Yugoslavia. Under the basic law of 1963, Kosovo received the status of an autonomous region with some independence. And according to the 1974 constitution, Kosovo Albanians were able to have representatives in the federal government, parliament and nominate candidates for presidential elections. However, only after the death of Tito, as for the same constitution, he was approved by the president for life. Thanks to the 60 – 70 reforms, Kosovo received Albanian civil servants in key posts, Albanian police and the University of Pristina, where Albanian was taught. Accents have shifted, it would seem, now the local Serbs would have to feel deprived of their rights.

With the death of Tito in 1980, the conflict broke out with a new force. The removal of censorship restrictions has caused an unprecedented flow of diverse information on both sides: each side presented itself as affected. Kosovo still did not have the status of a republic, and the Albanians were considered a minority in Yugoslavia, despite the fact that they constituted about 85% of the population in the province. The level of education in such a short time was virtually impossible to raise by a single university, therefore the low level of training caused outrage among Albanians, including the students themselves, who found it difficult to find work. A third of jobs in Kosovo were taken by the Serbian minority, while unemployment was growing among the Albanians. In response, the Kosovo authorities did everything to protect the ethnic Albanians, which was viewed by the Yugoslav Communist Party as an excess of power and a desire for separatism. The question has already been raised about protecting the rights of the oppressed Serb minority in Kosovo.

The region, even without the status of a republic within a federation, was in fact regarded as a special territorial entity. Slobodan Milosevic, in his speeches on the 24 – 25 Kosovo field on April 1987, also condemned nationalism and called for unity and the desire for coexistence. But he addressed first of all to the Serbs: expressing hope for the return of the Serbs to autonomy, he referred to the fact that Kosovo is the same historical homeland of the Serbs as the Albanians. Two years later, on the 600 anniversary of the battle on the Kosovo field, becoming president of Yugoslavia, Milosevic again recalled the historical significance of the region, but this time stressed that for Serbia Kosovo is not just one of the values, but the main center of culture and historical memory. Milosevic put an equal sign between the Serbs of 1389 of the year, opposing the Turkish threat, and the modern Serbs, who were striving for the national unity of the country. It was this passage, and not the praise of European tolerance and ethnic equality, that caused the greatest enthusiasm among the listeners. The words of Milosevic acquired an unequivocal interpretation in further quotations and comments, becoming the manifesto of Serbian restrained pride. Even the painful topic of the conflicts between the Serb communists and the Serb nationalists during World War II fell into shadow against the backdrop of the grandiose 600-year struggle for the Serbian national idea.

In 1989, the formal consolidation of a new domestic political course followed: at gunpoint tanks The Kosovo Assembly approved amendments to the Serbian constitution, which transferred control over the Kosovo courts and the police, and also provided the Serbian parliament with issues of social policy, education and language in Kosovo. The autonomy that was used by Kosovo in the time of Tito was abolished. Despite the rhetoric of a “common historical homeland”, Albanians were forced to seek work and housing outside of Kosovo, and family planning policies were also directed against the traditional Albanian family life.

At first, the resistance of the local population was peaceful: Albanians went on demonstration with Yugoslav flags, portraits of Tito and slogans in defense of the 1974 constitution of the year. But the centrifugal tendencies increased, in July 1990, the Albanian deputies announced Kosovo’s right to self-determination, but first there was talk of creating a republic within Yugoslavia. In 1991, the collapse of the country began, accompanied by war in Croatia, and the people of Kosovo have demanded independence. In the fall of 1991, a referendum with a 87% turnout and 99% approval of independence was held in the region. At the same time, the question of reunification with Albania was not even raised, the most closed and poor European country had just begun de-Stalinization. Recognized only by Albania, the self-proclaimed republic formed some parallel Yugoslav institutions in the areas of health care, education and taxes.

In 1997, a political crisis erupted in neighboring Albania, and in the summer of next year, the activities of the Kosovo Liberation Army, a dubious organization with foreign leadership, intensified. KLA units sometimes acted in a manner similar to their black-shirt counterparts a half century ago: the violence was directed not only at the Serbs and the Yugoslav authorities, but also at other ethnic minorities, such as the Roma. The cycle of revenge was repeated, but now the violence was simultaneous on both sides.

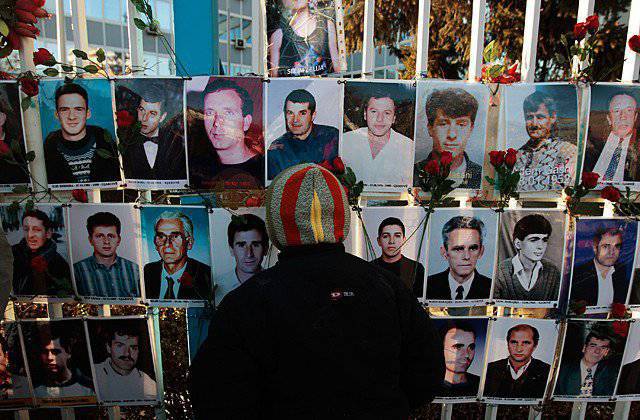

Actions from the Serbian and Kosovo sides, especially after the 15 January 1999 incident in Racak, require a separate comprehensive assessment already as a military conflict and a series of war crimes: as usual, in defending "their truth" both sides did not disdain anything. The “Racak Incident” became a pretext for NATO intervention, and the alliance eventually used military force against Belgrade. Albanians claimed that Serbian police units had shot civilians. In turn, representatives of Belgrade talked about an armed clash with KLA militants.

The subtotal was achieved by 1999, when hostilities ceased in Kosovo and the region came under the control of the UN transitional administration. The conflict, however, was never resolved: the provisional authorities failed to end the oppression and violence against the Serbs. The clashes continued until 2001, and flared again in 2004, when several thousand Serbs fled from Kosovo, and several dozen churches and hundreds of houses were damaged or destroyed.

In 2008, the last to date independence of Kosovo from Serbia took place. Despite Kosovo’s formal recognition of 108 by countries and its joining various international associations in February, the country is still not a single centralized authority: north of the Ibar River, where the 90% of the Serb minority resides, does not recognize the power of Pristina. The conflict continues, and today there is a danger of the next phase: contrary to the UN Security Council resolution banning any armed forces in Kosovo, except for international KFOR (“Forces for Kosovo”), Pristina expressed its intention to create a Kosovo army. It should be expected that in such an army there will be no Serbs, and this can only mean a complication of an already insurmountable conflict.

The centuries-old feud of two neighbors, each of whom regards Kosovo as their historical homeland, continues to this day.

Information