Danube campaign of the Eastern War

18 May 1854, the Danube army commanded by Ivan Fyodorovich Paskevich began the siege of Silistra. However, the siege was conducted extremely indecisively, since the Russian command was afraid of the entry of Austria into the war, which took an extremely hostile position towards Russia. As a result, the Russian siege was lifted in June, although everything was ready for a decisive assault, and retreated beyond the Danube. In general, the Danube campaign of the Eastern (Crimean) War for the Russian Empire ended ingloriously, albeit without serious defeats.

Prehistory 1853 Campaign

1 June 1853, St. Petersburg announced a memorandum on breaking off diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire. After that, Emperor Nicholas I ordered the Russian army (80 thousand soldiers) to take the Danube princedoms Moldavia and Wallachia subordinate to Turkey "as a pledge until Turkey satisfies the just demands of Russia." 21 June (3 July) 1853. Russian troops entered the Danubian principalities. The Ottoman Sultan did not accept the demands of Russia regarding the right to protect Orthodox in Turkey and nominal control over the holy places in Palestine. Hoping for the support of the Western powers - the British ambassador in Istanbul Stratford-Redcliffe promised in the event of war the support of England, the Ottoman Sultan Abdul-Mejid I on September 27 (October 9) demanded the cleansing of the Danube principalities from the Russian troops in two weeks. Russia did not fulfill this ultimatum. 4 (16) October 1853. Turkey declared war on Russia. October 20 (November 1) Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The Eastern (Crimean War) began.

It should be noted that Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich, who until then had rather successfully led the foreign policy of the Russian Empire, made a strategic mistake in this case. He thought that the war would be short-lived and small, ending with the complete defeat of the Ottoman Empire, which was not ready for war, and which would not be able to withstand the Russian troops in the Balkans and the Caucasus, and the Russian the fleet in the Black Sea. Then Petersburg will dictate the terms of the world and take whatever it wants. Of particular interest to St. Petersburg was the control over the Bosphorus and Dardanelles.

All this would have happened if not for the intervention of the Western powers. Sovereign Nicholas I was mistaken in assessing the interests of the great Western powers. In his opinion, England should have been left behind, he even offered to participate in the section of the “Turkish heritage”, believing that London would be satisfied with Egypt and some islands in the Mediterranean. However, in reality, London did not want to give Russia anything from the inheritance of the “sick man of Europe” (Turkey). After all, the strengthening of Russia's positions in the Balkans, in the Transcaucasus, and control over the straits dramatically changed the strategic position not only in several regions, but also in the world. Russia could completely block access to the Black Sea, making it a “Russian lake”; to expand possessions in the Transcaucasus and to be in dangerous (for the British) proximity to the Persian Gulf and India; to control the Balkans by dramatically changing the balance of power in Central Europe and the Mediterranean. Therefore, part of the British elite frankly worked to show St. Petersburg its neutrality, drawing Russia into the “Turkish trap” and at the same time setting France and Austria against the Russian Empire.

The French emperor Napoleon III during this period was looking for an opportunity to conduct a foreign policy adventure, which would return to France its former splendor, and create an image of a great ruler for him. The conflict with Russia, and even with the full support of England, seemed to him a tempting affair, although the two powers had no fundamental contradictions.

For a long time the Austrian empire was an ally of Russia and was obliged to Russian for the coffin of life, after the Russian army, under the command of Ivan Paskevich, in 1849, defeated the Hungarian rebels. From Vienna’s side in St. Petersburg they didn’t expect a dirty trick. However, Vienna also did not want to strengthen Russia at the expense of the Ottoman Empire. The sharp strengthening of Russia's position on the Balkan Peninsula made Austria dependent on the Russian country. Vienna was frightened by the prospect of the appearance in the Balkans of a new, Slavic state, which would all be indebted to Russians.

As a result, Nicholas I, with the "assistance" of the Foreign Ministry, led by the Englishman Karl Nesselrode, miscalculated in everything. There was a union of England and France, in which he did not believe. And Austria and Prussia, on whose support Nikolai Pavlovich counted, took a neutral hostile position. Austria began to exert pressure on Russia, actually playing on the side of the anti-Russian coalition.

Nicholas's confidence in the surrender of Turkey in the most negative way played on the combat capability of the Danube army. Her determined and successful offensive could thwart many of the plans of the enemy. Thus, Austria, with the victorious offensive of the Russian army in the Balkans, where it was supported by the Bulgarians and Serbs, would have been careful not to put pressure on St. Petersburg. But England and France simply did not have time to transfer troops to the Danube front by that time. The Turkish army on the Danube front half consisted of the militia (Redif), which had almost no military training and was poorly armed. Decisive strikes of the Russian army could lead Turkey to the brink of a military-political catastrophe.

However, the Russian corps, which, under the command of Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov, crossed the Prut in the summer, did not launch a decisive offensive. The command did not decide on such an offensive. Petersburg expected Turkey was about to throw out the white flag. As a result, the army began to decompose gradually. The theft was so widespread that it interfered with the conduct of hostilities. The combat officers were strongly annoyed by the ugly rampant predatory of the commissariat and the military engineering unit. Especially annoying meaningless buildings, which ended before the start of the retreat. Soldiers and officers began to realize that banal theft was taking place. In the middle of the white day, the treasury was plundered - no one will check what was built and what was not built, and how they built fortifications in the place left for good. The officers and soldiers quickly felt that the high command itself did not exactly know why it had brought Russian troops here. Instead of a decisive offensive, the corps were idle. This most negatively affected the combat effectiveness of the troops.

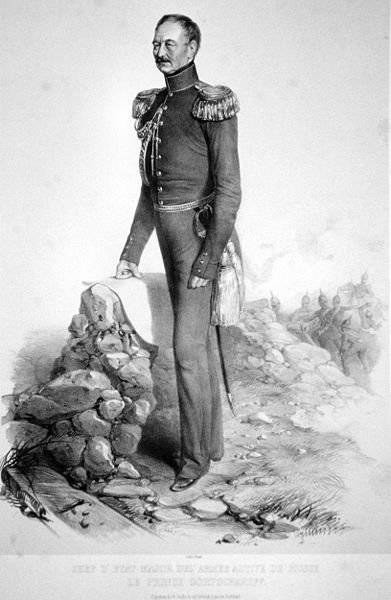

It should be noted that in the prewar period, Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich advocated a bold dash through the Balkan Mountains to Constantinople. The advancing army was supposed to support the landing, which was planned to land in Varna. This plan, if successful, promised a quick victory and a solution to the problem of a possible breakthrough of the European squadron from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea. However, Field Marshal Ivan Fyodorovich Paskevich spoke against such a plan. Field Marshal did not believe in the success of such an offensive. Paskevich did not want war at all, anticipating a great danger at its beginning.

Paskevich held a special position in Nikolai’s entourage. After the death of Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich Paskevich, in fact, he remained the only person whom the emperor fully trusted, as a man who was absolutely honest and loyal. Nikolai addressed Paskevich in the most important cases. Paskevich was the commander of the Guards Division, in which, being the Grand Duke, served as Nikolay, and, becoming sovereign, Nikolai Pavlovich continued to call him until the end of his life "father-commander".

Paskevich was a courageous man and was not afraid because he was old and lost his former determination, he was a stranger to adventures and in his restraint in his youth and prime. Hero of World War 1812, the winner of the Persians and Turks. For the Turkish campaign 1828-1829. Paskevich received field marshal's baton. In 1831, he took Warsaw, suppressed the Polish uprising, after which he received the title of Prince of Warsaw and became governor of the Kingdom of Poland. He stayed in this position until the Eastern War. Paskevich did not believe the West and was very afraid for Poland, in which he saw a ready-made anti-Russian bridgehead. And therefore he advocated an extremely cautious policy of Russia in Europe. Paskevich was cold about the emperor’s desire to save Austria during the Hungarian uprising. Although fulfilled the desire of Nicholas - suppressed the Hungarian uprising.

Paskevich was distinguished by a sober look at Russia and its order, he was an honest and decent man. He knew that the empire was sick and she shouldn’t fight the Western powers. He was far less optimistic about the power of Russia and her army than the emperor. Paskevich knew that the army was struck by the theft virus and the presence of the “peacetime generals” caste. In peacetime, they were able to convincingly conduct parades and parades, but during the war they were indecisive, inert, lost in critical situations. Paskevich feared the Anglo-French alliance and saw in him a serious threat to Russia. Paskevich did not believe in either Austria or Prussia; he saw that the British were pushing the Prussians to seize Poland. As a result, he was almost the only one who saw that a war with the leading European powers was awaiting Russia and that the empire was not ready for such a war. And that the result of a decisive offensive in the Balkans could be the invasion of the Austrian and Prussian armies, the loss of Poland, Lithuania. However, Paskevich did not have the fortitude that would allow him to resist the war. He could not open Nicholas eyes.

Not believing in the success of the war, Paskevich changed the earlier plan of the war to a more cautious one. Now the Russian army was to occupy the Turkish fortresses on the Danube before advancing on Constantinople. In a note filed to the 24 emperor in September (6 in October) 1853, Field Marshal Paskevich recommended not to start active military actions first, since this could “put against himself, besides Turkey, the strongest powers of Western Europe.” Field Marshal Paskevich advised, even with active offensive actions of the Turkish troops, to adhere to defensive tactics. Paskevich proposed to fight the Ottoman Empire with the help of the Christian peoples who were under the Ottoman yoke. Although he hardly believed in the success of such a strategy, he was extremely skeptical of the Slavophiles.

As a result, Paskevich’s caution and the complete failure of the Russian government on the diplomatic front (they missed the Anglo-French alliance and did not notice the hostile attitude of Austria and Prussia) created extremely unfavorable conditions for the Danube army from the very beginning. The army, feeling the uncertainty of the upper ranks, trampled on the spot. In addition, Paskevich did not want to give significant connections from his army (in particular, the 2 Corps), which stood in Poland to strengthen the Danube army. He exaggerated the degree of threat from Austria, conducted all sorts of exercises, campaigns.

Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov

Correlation of forces

For actions in the Danube principalities, the 4 Corps (more than 57 thousand soldiers) and part of the 5 Infantry Corps (more than 21 thousand people), as well as three Cossack regiments (about 2 thousand people) were assigned. The artillery park of the army numbered about 200 guns. In fact, the whole burden of the fight against the Ottomans fell on the Russian avant-garde (about 7 thousand people). The Russian avant-garde fought against the Turkish army from October 1853 until the end of February 1854.

80-thousand the army was not enough to firmly conquer and hold the Danube principalities of the Russian Empire. In addition, Mikhail Gorchakov scattered troops at a considerable distance. And the Russian command had to take into account the danger of a flank threat from the Austrian Empire. By the fall of 1853, this danger became real, and in the spring of 1854, it became the predominant one. Austrians feared more than the Ottomans. Fearing the blow of Austria, the Russian army went over to the defense first, and then left the Danube principalities.

Moldovan and Wlachian troops numbered about 5-6 thousand people. Local police and border guards numbered about 11 thousand people. However, they could not provide substantial assistance to Russia. They were not hostile to the Russians, but they were afraid of the Ottomans, they did not want to fight. In addition, some elements (officials, intelligentsia) in Bucharest, Iasi and other cities focused on France or Austria. Therefore, local formations could perform only police functions. Gorchakov and Russian generals did not see much benefit from local forces and did not force them to do anything. In general, the local population was not hostile to the Russians, the Ottomans were not loved here. But the locals did not want to fight.

The Ottoman army numbered 145-150 thousand people. Regular units (nizam) were well armed. All rifle units had rifled rifles, in the cavalry part of the squadrons already had a union, the artillery was in good condition. Troops trained by European military advisers. True, the weak point of the Turkish army was the officer corps. In addition, the militia (almost half of all military forces) was armed and trained much worse than regular units. In addition, the Turkish commander Omer Pasha (Omar Pasha) had a significant number of irregular cavalry - bashi-bazouks. Several thousand bashi-bazouks performed intelligence and punitive functions. By terror, they suppressed any resistance from the local Christian population.

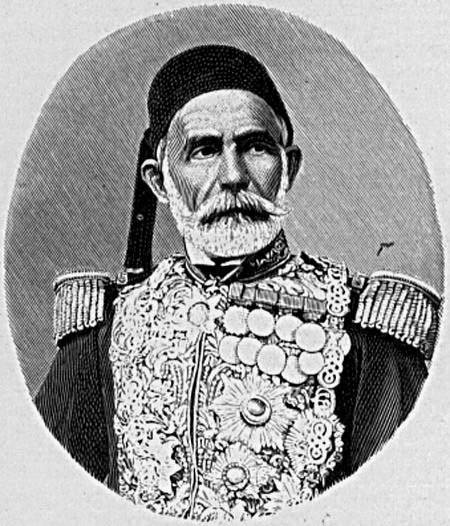

Omer Pasha (by origin Serb Mikhail Latas) was the son of a junior officer in the Austrian army. He was a teacher, graduated from cadet school. Due to family problems, he moved to Bosnia. He converted to Islam and became a teacher of drawing the children of the commander of the fortress in Vidin. For success, he was sent to Constantinople, where a teacher of drawing at the Istanbul Military School, and then a teacher of the heir to the throne, Abdul Mejid. He became adjutant of Khozrov Pasha and received the rank of colonel. After Abdul Majid became the sultan, he received the title of Pasha. During the war with Egypt he reached the rank of major general. He fought with rebels and rebels in Syria, Albania and Kurdistan. In 1848-1849 took part in the occupation of the Danube principalities, in 1850, distinguished himself during the suppression of the uprising in Bosnia Krajina. Omer Pasha drowned the rebellion in the blood. In 1852, Omer Pasha led the fighting against Montenegro. At the beginning of the Eastern War, Omer Pasha led the Turkish troops in the Balkans.

Omer Pasha belonged to the “party of war”. During the diplomatic negotiations, he tried by all means to induce the Sultan to war with the Russian Empire. The Turkish dignitary believed that there would no longer be a better situation for fighting Russia, and it was necessary to seize the moment when Britain and France were ready to take the side of Turkey. Omer Pasha was not a great commander, he mainly distinguished himself in suppressing the uprisings. At the same time, he cannot be denied the presence of certain organizational skills, personal courage and energy. But his success on the Danube front was more connected with the mistakes of the Russian command than with the talent of the commander. And Omer Pasha could not even use them to the full.

The Turkish army was helped by many foreigners. The headquarters and the headquarters of Omer Pasha had a significant number of Poles and Hungarians who fled to Turkey after the collapse of the uprisings of the 1831 and 1849 years. These people often had a good education, combat experience, could give valuable advice. However, their weakness was hatred of Russia and the Russians. Hate often blinded them, forcing them to take their desires for reality. So, they greatly exaggerated the weaknesses of the Russian army. In total, the Turkish army was up to 4 thousand. Poles and Hungarians. There was even more benefit from French staff officers and engineers who began arriving at the start of 1854.

Omer Pasha

The first measures of the Russian command in the Danube principalities

In July, the 1853 of the year, the Russian authorities banned both gospels (and Moldavia and Wallachia) to continue relations with Turkey, and the contributions that the Danube principalities were obliged to make in favor of the Turkish treasury were sequestrated. Russia was no longer going to tolerate the transfer in Porto (and even through the inviolable diplomatic envoys) of secret reports from the rulers who revealed the situation of the Russian army and the support of the Turkish treasury with financial transfers from Moldova and Wallachia.

In response, Istanbul ordered the kings to leave the borders of their principalities. The English and French consuls also left the Danube principalities. The British government said Russia violated Porto’s sovereignty. The British and French press accused Russia of occupying Moldavia and Wallachia.

It must be said that after the escape of the rulers, Gorchakov left the entire old administration of the principalities in the field. That was a mistake. This "liberalism" could not fix anything. England and France were going to break with Russia, and Turkey was ready to fight. In St. Petersburg, this is not understood. The former Moldovan and Wlach officials retained the threads of the administration, the court, the city and village police. And it was hostile to Russia (unlike ordinary people). As a result, the Russian army was powerless against an extensive spy network, which operated in favor of Turkey, Austria, France and England. In addition, in the first stage, when England had not officially entered the war with Russia, the British and their local agents continued to trade along the Danube. Thus, London received all the information about the position of the Russian forces in the Danube principalities.

Emperor Nicholas tried to play the national and religious card - to raise against the Ottomans Serbs, Bulgarians, Greeks and Montenegrins. However, here he faced several insurmountable obstacles. First, in the previous period, Russia advocated legitimism and was extremely suspicious of any revolutionary, national liberation movements and organizations. Russia simply did not have secret diplomatic and intelligence structures that could organize such activities in the possessions of Porta. Nicholas himself had no experience of such activities. And literally starting everything from scratch was pointless. Needed was a long preliminary, preparatory work. Moreover, in Russia itself, there were many opponents of such a course at the top. In particular, the Foreign Ministry, which headed Nesselrode, who feared international complications, spoke out against Nikolai’s initiative.

Secondly, the secret networks had England and Austria, but they were opponents of pro-Russian currents and did not want uprisings on the territory of the Ottoman Empire at that time. Austria could play the greatest favor in arousing the Christian and Slavic population, but it was opposed to Russia.

Thirdly, the Christians of the Balkans themselves from time to time raised uprisings that the Ottomans drowned in blood, but during this period they waited for the arrival of Russian troops, and not some hints that the matter should be taken into their own hands. The fantasies of Slavophiles that there is a Slavic brotherhood, that the Serbs and Bulgarians themselves can throw off the Turkish yoke, only with the moral support of Russia and immediately ask for the hand of the Russian emperor, were far from reality.

Fourthly, the Turkish authorities had extensive experience in identifying dissatisfied and suppressing uprisings. Numerous formations of the Turkish police, army and irregular troops were located in the Slavic regions.

To be continued ...

Information