Anarchists in the Soviet Labor Movement

What role did the anarcho-syndicalists play in both revolutions of the beginning of the 20th century and the establishment of proletarian power?

Both the February and October revolutions of 1917 were carried out by a conglomerate of socialist and nationalist movements - from the Left SRs to the Armenian Dashnaks. In everyday consciousness, these events are usually associated only with the Bolsheviks. Meanwhile, the Russian anarchists also played a significant role in both revolutions and in the establishment of proletarian power. The number of members of their movement and various kinds of circles in the fall of 1917 was about 30 thousand people, while the activity of the anarchists was concentrated in both capitals and on the Baltic and Black Sea fleets... They also played an important role in the labor movement, including in the post-revolutionary years.

Libertarians occupy factories

Back at the end of 1917, anarchists and syndicalists had a noticeable influence among factory committees (FZK). At the All-Russian Conference, the FZK in October and V Petrogradskaya in November, the libertarians had 8% and 7,7% delegates, respectively, having the third largest fraction after the Bolsheviks and the then not yet split SRs, overtaking the Menshevik Social Democrats. According to the historian G.Maksimov, at the First All-Russian Congress of Trade Unions, held in January of the 1918, the syndicalist faction, which included several maximalist Socialist Revolutionaries, consisted of 25 delegates, that, at the 1 representation rate, the delegate to 3-3,5 had a thousand 88 thousands of workers represented . According to other sources, 416 delegates representing 2,5 million workers in Russia included 6 syndicalists (among them Maximov and Shatov), 6 maximalists, and 34 non-partisans. According to the most "pessimistic" calculations, it turns out that anarchists represented only 18 thousands of people; if you count by percentage, you get an averaged figure - 36 thousand.

Subsequently, the number of workers represented, even according to the most optimistic data of Maximov, gradually decreased: at the second trade union congress in 1919 there were 15 delegates, or 53 thousands of workers, and at the next (1920 year) there were a total of 10 delegates, or 35 thousands. Naturally, this tendency was characteristic not only of anarchists. A gradual decrease in the influence of all parties is also noted according to the data of the Soviet historian S. N. Kanev. He also gives a different assessment of the presence of anarchists in trade unions: according to her, at the I congress there were 6 anarcho-syndicalists and 6 anarchists from other trends, in total they gave 2,3% of the total number of 504 delegates, that is, anarchists represented almost 60 thousands workers; 5 (0,6%, or 21 one thousand) on the second, 9 (0,6%) on the third, and 1921 anarchist communist and 2 anarchists from other trends (10%) attended 0,4 in May - this was the last trade union congress on which anarchists were represented. By 1921-1922, the libertarians' representation on a nationwide and provincial scale has come to naught.

The anarchists nevertheless had living connections with the workers in the field. Soon after the formation of a new anarchist group at the Triangle Petrograd Plant in December 1917, 100 people entered it. The capital's port workers experienced the particularly strong influence of the anarchists. The congress of the Petrograd port workers, in contrast to the moderation of workers' control, approved the call for expropriation. In Odessa, located at the other end of the country, the local anarchist federation, in addition to the syndicalist group, also included groups at the enterprises: the Anatra plant, the Popov factory, and the tanneries and seamen of the merchant fleet. Odessa anarcho-syndicalist Piotrovsky participated in the work of the First All-Russian Conference of Factory and Factory Committees. There, the Kharkov libertarian Rotenberg, representing the plant of the Universal Electricity Company, was delegated to the local CA of the factory committees.

In Kharkov, libertarians acted in the locomotive depot. According to the memoirs of A. Gorelik, “whole railway sections were under the ideological influence of anarchists,” and the central body of postal employees was edited by an anarchist. G. Maximov claims that at the All-Russian Congress of postal and telegraph workers "more than half of the delegates followed" anarchists, and in Moscow, as Maximov said, syndicalists dominated the trade unions of railway workers and perfumers. As a result of the efforts of Comrade Anosov, the journalism of the Volga water transport workers' union was based on libertarian principles. In Moscow at the telephone factory the anarchist M. Khodunov was at one time the chairman of the branch committee.

According to Gorelik, in Yekaterinoslav (present-day Dnepropetrovsk), in which he then lived, the secretaries in unions of metalworkers, doctors, woodworkers, shoemakers, tailors, laborers, mill workers and many others were anarchists. In the factory committees of the Bryansk plant, the Gantke plant, the Dnieper, Shaduard, Trubny, Frunklin, Dnieper workshops, the Russian society (Kamenskoe) and many other anarchists were in large numbers and most were the chairmen of these committees. The Yekaterinoslav Federation of Anarchists was the "manager" of the 80-thousandth demonstration in honor of October. According to Gorelik, anarchists in Kharkov at the Locomotive Plant had such a great influence at the end of 1920, that when they arrested the participants of the Nabat congress, 5 of thousands of workers staged a solidarity strike.

The information that anarcho-syndicalists had an influence on the workers of the Yekaterinoslav province is confirmed by the fact that at the end of 1917, A.M. was elected chairman of the Pavlograd district executive committee. Anikst, who later broke with the Voice of Labor group and joined the ruling party. In the south, syndicalism began to spread among cement workers and dockers of Ekaterinodar and Novorossiysk.

Historian Kanev did not believe that anarchists achieved a majority in any of the FZKs, but in the fall of 1918, anarcho-syndicalists won 60% of the votes in the election of the delegate council of the Petrograd Post Office. In April, 1918 of the anarcho-syndicalists represented 18% of the industry workers at the III congress of postmen and telegraph operators 6,7. Anarchist Grigoriev presented a draft advocating the principles of decentralization and federalism. At his suggestion, the central bodies of the postal and telegraph union were to be created only at the provincial and regional levels. After a heated debate, the syndicalists joined the closely related project of the Left Social Revolutionaries, also standing on the platform of federalism, and together with a group of non-party people, they opposed the Bolsheviks, but lost by a small margin: 93 votes for the bloc of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and anarchists against 114 for the Bolsheviks. And yet, until the defeat of the Left Socialist Revolutionary Party in July of 1918, they, together with anarchists, acting in governing bodies, had unsuccessfully defended the decentralized structure in practice.

Autonomy and freedom

Anarchists, acting in trade unions, everywhere tried to defend the independence and autonomy of local cells, the federal structure of the association. And the Bolsheviks, in turn, tried by any means to get the governing bodies in their hands.

A few examples. Indicative of story Soviet relations with the trade union of railway workers at the end of 1917 — the beginning of 1918. The executive committee of this union (Vikzhel) came out with open opposition to the Bolsheviks, who had only a few people from about 40 members in it. Vikzhel demanded the creation of a "homogeneous socialist government" and threatened with a general strike on the railways. The executive committee of the trade union directly controlled the work of the railways. Then the Bolsheviks went to a split — they convened their own railway congress, which elected another executive committee (Vikzhedor), which consisted of Bolsheviks and left-wing Socialist-Revolutionaries. The new body received the support and recognition of the government, a member of the Vikzhedor Rogov became the people's commissar for railways. Further, in order to undermine the influence of Vikzhel, the authorities released a provision according to which the management of each railway was transferred to the elected railway workers and employees of the council, and all the country's railways to the All-Russian Congress of railway deputies. Already in March, 1918, however, the People’s Commissariat of Communications received dictatorial powers in the management of railways.

As for the organizations of water transport workers, the Bolsheviks managed to implant centralism only by the beginning of March 1919. Anarchists, like postal workers, opposed centralization at their first industry congress. The Bolsheviks were in the minority, and the congress was in principle in favor of creating a single sectoral union led by the “Tsekvod,” but according to Kanev, the provisional statute did not underline the principles of centralization and discipline. The Central Committee of Volga Basin Workers (“Center-Volga”) pursued its independent policy and did not submit to the “Tsekvod”, in turn, some small unions attempted to pursue an autonomous policy in relation to the “Centrovolga” as well. In February, 1919, the second congress of water transport workers overcame the “localism” of the regional representative bodies, simply eliminating them and transferring more power to the “Tsequod”.

That is, the Bolsheviks went to a split when it was profitable for them, while struggling with the "local" and "guild" interests of those unions in which they did not find support.

Anarchists had a certain influence among the miners. Even before the First All-Russian Congress of Trade Unions, anarcho-syndicalists organized 25-30 thousands of Donbas miners in the Debaltseve region on the platform of the American association Industrial Workers of the World (IRM). The American historian P. Eurich clarifies: Donbass miners included in their platform an introduction to the statutes of the Syndicalist Union of the IWW: “The working class and the exploiting class have nothing in common. As long as hunger and deprivation prevail among the millions of working people, and a minority of the exploiting class leads a prosperous life, there can be no peace between them. The struggle between these classes should continue until the workers of the whole world organized as a class seize land and the means of production and get rid of the system of hired labor. ”

The union was defeated by the Cossacks, who killed its organizer Konyaev.

In the Cheremkhovo coal basin (near Irkutsk), the anarchist A. Buyskikh served as chairman of the trade union of miners and head of the executive committee of the Cheremkhovsky Council of Workers 'and Peasants' Deputies. Already in May, the 1917 of the year, under his leadership, the miners seized one of the mines and the plant, transferring control to the working committees. And at the end of December - beginning of January, 1918 of the year, full socialization was carried out: the transfer of mines and factories to the ownership of the Cheremkhovsky Council of Deputies, with full local management of elected mine and factory committees. The end of this undertaking put an uprising of the Czechoslovak Corps.

Bakers - the last stronghold of syndicalism

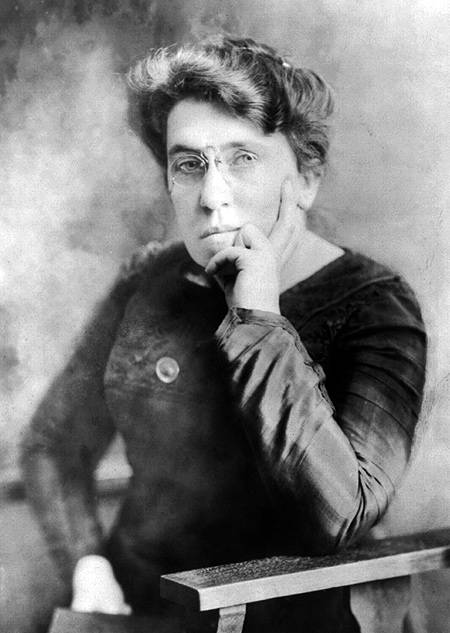

Under existing conditions, unable to act freely on the ground, anarcho-syndicalists had to either get bogged down in “union parliamentarism” with a weak hope of achieving leadership of industry alliances on an all-Russia scale, or create their own labor movement independent of the state. The attempt to form the General Confederation of Labor remained only an attempt, but in 1918, in some places, such splitting attempts were successful: the bakers of the Rogozhsky district of Moscow were separated from the general union of food industry workers. In general, among the bakers, libertarians held very strong positions. In 1918, anarcho-syndicalists controlled the bakers trade unions in Kiev, Kharkov and Moscow. According to the memoirs of the famous American anarchist Emma Goldman, who lived two years in Soviet Russia, the union of bakers was very militant. Its members spoke of trade unions controlled by the state as the lackeys of the government. According to the bakers, the trade unions did not have any independent functions, they performed the duty of the police, and did not provide the workers with votes.

One of the leaders of the Moscow bakers, anarcho-syndicalist Nikolai Pavlov, wrote in The Free Voice of Labor, and then he entered the Union of Anarchist Syndicalist Communists; at the II All-Russian Congress of Food Industryists, anarcho-syndicalists drew up a resolution on G. Maximov's theses. In the midst of military communism and the red terror, libertarians did not hesitate to openly call for a struggle for the establishment of a free-Soviet powerless system and the transfer of economic management into the hands of workers and peasants. By the beginning of 1920, it was the only Moscow trade union, part of which remained loyal to libertarian principles.

When the authorities tried to replace the leadership of the union with the Bolshevik, the position of the bakers was adamant: they threatened to stop working if they were not allowed to choose their delegate. When the Cheka gathered to arrest the elected candidate Pavlov, they surrounded him, which allowed him to safely get home. Thanks to the ultimatum put forward, the bakers achieved recognition of their choice by the authorities.

Pavlov more than once was elected by the workers to the Mossovet. In February, 1920 of the year at the general meeting of bakery No.3, he received overwhelming support, only 14 people voted against his candidacy. At the First and Second Congresses of the Union of Food Workers, which united bakers, confectioners, and millers, the syndicalists had 12-18 votes, representing 10-12% of delegates. On the ground, they had support in Moscow, Kiev, Odessa and Saratov.

Maximalist Social Revolutionaries, Kamyshev and Nyushenkov, acted among the bakers, the first of them held leading posts in the union, and even the Left Social Revolutionaries, one of whose leaders, I. Steinberg, was elected by them to the Moscow Soviet. At the same time, as G.P. Maximov claimed, anarchists and maximalists acted in concert.

Kronstadt support

At the beginning of 1921, a number of Bolsheviks — Podvoisky, Muralov, Yagoda, Menzhinsky, and others — noted the threat that the working class in the large proletarian centers would come out from under the influence of the Bolshevik RKP and the anti-Soviet protests. 23 February 1921 in Moscow workers unrest broke out: strikers from the factory of Goznak, unhappy with the decrease in rations, staged a three-thousand-day demonstration that stopped work at several other factories. As a result of clashes with the troops were victims. The next day, Moscow factories exploded with rallies, some partially stopped work. The strike wave rose, demonstrations took place on the streets, in which thousands of people took part; thousands more were on strike. In the Moscow Cheka, the activity of the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries was noted.

Throughout February, Petrograd was worried about 1921. In the first half of the month, more than a thousand tramsmen briefly went on strike, almost four thousand workers of the Baltic Shipbuilding Plant, staged a strike and workers from the Cable Plant. Other enterprises held meetings and rallies. 24 February 300 workers at the Pipe Plant went outside. Thousands of people gathered on Vasilievsky Island on 2,5. Authorities responded by imposing martial law. But strikes and riots continued in the first week of March. For example, March 3 did not operate the Baltic, Gvozdilny, Aleksandrovsky and Putilovsky factories.

The Cheka's operational reports contain information that anarchists in Petrograd tried to organize support for the insurgent Kronstadt. In the premises of the Voice of Labor group, according to the Bolsheviks, the appeals of Kronstadters were reprinted, and from there they were distributed. The assembly of the Arsenal plant 7 in March 1921 of the year passed a resolution on joining the rebels, and also elected a delegation to communicate with them as part of the anarchist, Social Revolutionary and Menshevik (arrested by the Cheka). 14 in March at the factory "Laferm" security officers discovered anarchist proclamations.

Moscow anarchists in the days of Kronstadt tried to organize an “Anarchist Action Council”. Representatives of various trends, up to the most loyal “anarcho-universalists”, distributed leaflets calling for support of Kronstadters. At the factories, as the Bolshevik leadership noted, libertarians acted in concert with the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. In particular, at the Moscow factory of Bromley, which adopted the Pro-Standstadt resolution of 25 in March, leftist Social Revolutionary I. Ivanov and anarchist Kruglov headed the political opposition to the regime. Anarcho-universalist V. Barmash spoke at rallies. But nevertheless, it is worth noting that the Mensheviks with the Socialist-Revolutionaries in the KGB reports are mentioned much more frequently, therefore, their role in the working environment was more noticeable.

The defeat of the anarchist-labor movement

In response to the strike wave of 1921, the Politburo decided to tighten the arrests of all workers' activists and members of opposition parties. Specifically, this was expressed in the order of the Cheka for all provincial emergency teams to “withdraw” anarchists, Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks from among the intelligentsia, as well as their active representatives in the factories. At the same time, it was necessary to proceed with caution with the main working mass: not to make arrests in full view, and to take all measures to disintegrate the crowd, including the “communists”.

A week later, on the night of March 8, more than 20 anarchists were arrested, including members of the executive bureau of the RKAS, Yarchuk and Maximov; in Petrograd and Moscow, a pogrom was inflicted in the Voice of Labor publishing house. The arrests of anarcho-syndicalists took place all over Russia, they were accused of wanting to participate in the organization’s congress scheduled for April 25 on 1921. Maximov and Yarchuk were kept in the Tagansky Prison, in May they were joined by members of the Nabat, Wolin and the Gloomy. The publishing house itself was closed. As the KGB admitted, the mass arrests in Petrograd played a role, depriving the strike movement of organized leadership.

After the suppression of the Kronstadt uprising of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party, it was recommended not to allow the legalization of the activities of anarchist groups and the opening of clubs, but to wage the most persistent ideological struggle with them. Moreover, in addition to supporting the anarchists of the uprising, they were blamed "for their performances in factories, their agitation and work in the peasant union, their corrupting and disorganizing influence on our [RCP] work, an attempt to corrupt some of our workers' alliances, as a union of food industry workers", that is, in fact, any syndicalist activity.

The leadership of the Cheka, in turn, offered to carry out repression against anarchists as they become active. Even earlier, the Chekists recommended clearing the education system of anarcho-syndicalists. Lenin wanted to create a commission at the organizing bureau of the Central Committee that would pursue the governing trade-union bodies, which was done on January 1 of 1922. By March 1922, anarchists were no longer represented at trade union congresses.

Even earlier, the condition for the open activity of “anarcho-universalists”, loyal to the leadership of the country before the start of Kronstadt, was their complete control of the authorities, lack of criticism and agitation. The Chekists emphasized the inadmissibility of the work of these most committed anarchist regimes among the workers. At the same time over them certainly had to be established observation. And if suddenly it turned out that their performances attracted many listeners, they tried to occupy their premises under one pretext or another.

In the future, the Bolsheviks tolerated some of the most exotic organizations of anarchists insofar as they recognized their existence — as a compromising anarchist movement — as a whole desirable.

At the same time, the legal anarchist-labor movement in the USSR was discontinued, and with the scope with which it acted in the first post-revolutionary years, it did not revive.

Information