Silent successes of China in the post-Soviet space ("Open Democracy", UK)

The quiet but obvious penetration of China into Eastern Europe and Central Eurasia, into the region, which is an ingenious mixture of former empires, ambitious hegemons and opportunistic small states, may well become an unexpected variable. This is not an expanded trade mission, it is a presence that has the potential for cultivating and projecting influence on space, which is fragmented and subject to active rivalry, and this presence may well lead to the collapse of Western hopes for regional democratization.

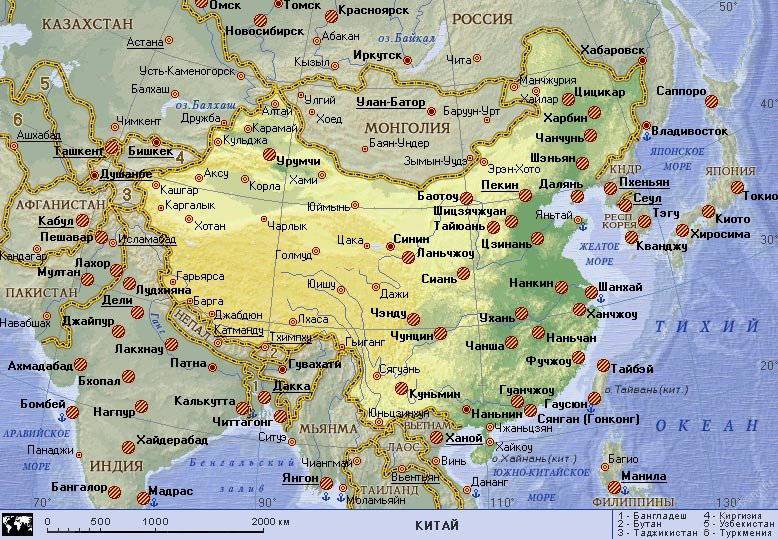

After the end of the Cold War, the main regions of the former Soviet Union ceased to be a meeting place between the West and the Eastern Bloc and turned into a zone of rivalry. Despite Russia's relative rebirth under Putin, Moscow no longer has a monopoly on power in this vast region. Together, this vague post-communist territories have become important points of interest for a number of already established and emerging powers, that is, for Russia, the European Union, Turkey, the United States and more and more for Iran. China, which recently surpassed Japan and became the second largest economy in the world after the United States, is increasingly showing itself as a serious player in this vast area, quite remote from the traditional spheres of influence of Beijing in the Asia-Pacific region and in Central Asia.

Diversification and geopolitics

China’s interest in this region is linked to Beijing’s global economic ambitions. Its strong trade relations and investments span the entire globe, from copper mines in Africa to recently received positive pecan nuts in North America, so Eastern Europe and Central Eurasia represent the last frontier for Chinese economic expansion. China’s foreign currency reserves now exceed 3,2 trillion dollars, and Beijing is seeking to diversify its global investment portfolio and is trying to create a key link in the trade route from China to Europe along the New Silk Road route. In the past ten years, trade between China and Central and Eastern Europe has grown by an astounding 32% per year, reaching 2010 a billion dollars in 41,1 year, and he hopes to increase this figure to 100 billions by year. Beijing actually invests its money where it has its interests, and thus continues its investment and credit boom. Belarus, which is largely isolated in Europe because of its authoritarian regime, enjoys Beijing’s generosity in the form of a recently issued loan worth over 2015 billion dollars. In Moldova, China bypassed both the European Union and Russia, giving the country a royal loan of 1,6 a billion dollars at a low interest rate. Ukraine has also benefited from the flow of Chinese investments in infrastructure, agriculture and energy projects. Even the Caucasus causes more and more interest in China. But perhaps the most impressive is the opening of a 1 billion-dollar credit line by Beijing to support Chinese business investment in this region.

The entry of China into Eastern Europe and Central Eurasia does not impress the geopolitical power game. At least for now. At the same time, Chinese investment — usually free from hidden human rights requirements and government positions made when receiving Western dollars — can often be problematic because of its foggy nature. Moreover, sometimes global Chinese investment served as a "losing leader" for gaining less tangible values in the form of geopolitical influence and corresponding leverage.

In Eastern Europe and Central Eurasia, where regional power dynamics is largely multipolar, China's high costs can create a platform for a real geopolitical role in the future. Other elements of interest to China in Eastern Europe can also be surprising. Technological cooperation with Russia in the defense sector, apparently, is today on a downward trend, but China has managed to maintain awareness of the development of Russian military equipment through the establishment of closer relations with countries such as Ukraine and Belarus. At present, China has shown interest in demonstrating its flag at the regional level, and this is being done both with the help of unexpected airborne exercises and due to the increasingly frequent appearance of ships of the Chinese naval forces in the Mediterranean.

Of course, China currently has neither the resources nor the political will to move to Eastern Europe and Central Eurasia as a contender for the role of the hegemon. However, the presence of Beijing in this region is unlikely to be endlessly only economic in nature. In fact, given the predominance of strong states and associations in the region, the role of China will inevitably have international implications. As the stakes of the Middle Empire increase in this region, the same will happen with its political role and desire to act more directly to ensure its interests. In the long run, current economic investment can help shape China’s significant influence, including in the capitals of Eastern European countries.

Credits, investments and autocracy

The growing role of Beijing in this region will have another medium-term effect, in addition to economic development. Given the increase in investment in Eurasia, often associated with special conditions or rates, China has the opportunity to become the first in the list of lenders and investors in this region. Beijing is actively opposed to all kinds of reservations by the United States and the European Union regarding track record and democratic attestations, and therefore the set actively used by the West for democratization is likely to undergo additional tests.

“Developing countries seem to value contracts with China, especially if China offers investments that, with the exception of accepting the“ one-China ”policy, do not impose any conditions,” the research note published in the middle of 2012 says German Marshall Fund.

The penetration of China into this region may further complicate the situation due to the provision of a “lifeline” to autocratic regimes, which until recently could only rely on Moscow or on local sources in order to avoid receiving financial resources due to various demands. This can have very important implications for the region: Western economic development programs (at least from the outside) are aimed at supporting selective economic growth, while unencumbered funding only strengthens the status quo.

Even worse, the countries of this region can make a choice in favor of the model present today in different parts of Central Asia, and its meaning is that the existing regimes of strong power set Washington, Moscow and Beijing against each other in order to obtain the most advantageous investment packages and aid packages, while hopes for democratization or liberalization in the future remain weak. In a sense, a similar process is already occurring, since the increase in funding flows from Beijing roughly coincides with a period of stagnation in the democratic development of the Central Asian region.

The growing role of China in post-communist Eurasia has many potential benefits, not least of which may be due to greater economic growth. However, the fragility - and sometimes the complete absence - of democratic institutions in Eastern Europe and Eurasia makes it a worrying prospect in Chinese dollar diplomacy. The Chinese geopolitical influence in this region may not noticeably grow for some time, however, from the point of view of the West’s program of assistance to democracy, it is high time to start planning and re-equipping, given China’s great successes.

Information