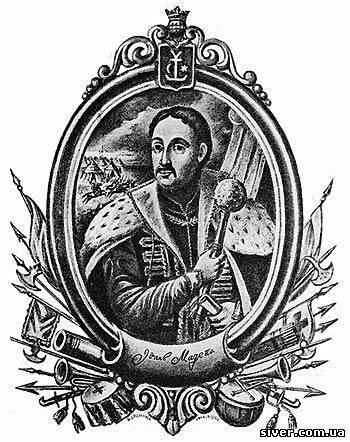

Khmelnitsky

Perhaps, more books and articles have been written about Khmelnitsky than about all the other hetmans taken together, but almost all historians concern only the last years of his life. The reason for such a lack of attention to the youth of the Hop's father is obvious: he lived just like thousands of other soldiers of Speech Pospo. He was born in the family of a poor nobleman around 1595 of the year, in his youth he took a course in grammar, poetics and rhetoric in the Lviv Jesuit College — in a word, the usual classic course of the then nobleman. It is reliably known that in the year 1620 he, together with his father, took part in the Moldovan campaign of hetman Stanislav Zolkiewski and received the baptism of fire in the battle with the Turks near Tsetsora. This battle ended not only in a crushing defeat for the Polish army, but also in the death of Bogdan’s father. The young man was captured, from where his mother bought it. Then Khmelnitsky fought in all the wars that led the Commonwealth. In 1633, the king awarded him a saber for taking part in the war with Muscovy.

By his fiftieth birthday Khmelnitsky clearly ended his career, becoming Chigirinsky warden. It would seem that waiting for his calm old age in his farm Sabbaths and memories of a dashing youth. But fate decreed otherwise. Widowed, Khmelnitsky decided to take a new wife, but his darling was kidnapped by his neighbor, Chigirinsky sub-kingdom, Daniel Chaplinsky. By the way, along with the farm. Indeed, what could be trivial. True, Khmelnitsky’s rights to the farm were very controversial. Insulted Bogdan tried to call the offender to a duel, but was ambushed and miraculously escaped. He had to complain to the crown hetman, then the litigation began, which Khmelnitsky lost - the only consolation for him were the ZNT 130 as compensation for Shabot. Returning from Warsaw with nothing, Khmelnitsky continued to complain about Chaplinsky, who in (howling accused Bohdan of treason and relations with Tatars. Khmelnitsky was preparing for an uprising or not - is unknown, but he was arrested by order of the crown hetman Pototsky. He was arrested soon. Khmelnitsky was arrested. Soon Khmmelnitsky was arrested. to run, and 11 December 1647 he and his son arrived in Zaporizhzhya Sich, and from there went for help to the Crimea. The moment for the request was successful. The Crimean Khan was unhappy with Poland, as she inaccurately paid an annual “gift” that he paid off raids, and besides, the peninsula had a poor harvest and, as a result, livestock mortality. The Tatars were not averse to compensating for their losses by plundering during the war. Khan agreed to help Khmelnytsky and put at his disposal a detachment of four thousand soldiers under the command of Perekop Murza Tugay-Bey. So on one side of the barricades were sworn enemies - the Tatars and Cossacks, although there was no trust between the new allies. As a hostage, the Khmelnitsky Timosh remained in Bakhchisarai, and Tugay-beat in the Cossack camp guaranteed, that Khan will not hit Khmelnitsky in the back.

By his fiftieth birthday Khmelnitsky clearly ended his career, becoming Chigirinsky warden. It would seem that waiting for his calm old age in his farm Sabbaths and memories of a dashing youth. But fate decreed otherwise. Widowed, Khmelnitsky decided to take a new wife, but his darling was kidnapped by his neighbor, Chigirinsky sub-kingdom, Daniel Chaplinsky. By the way, along with the farm. Indeed, what could be trivial. True, Khmelnitsky’s rights to the farm were very controversial. Insulted Bogdan tried to call the offender to a duel, but was ambushed and miraculously escaped. He had to complain to the crown hetman, then the litigation began, which Khmelnitsky lost - the only consolation for him were the ZNT 130 as compensation for Shabot. Returning from Warsaw with nothing, Khmelnitsky continued to complain about Chaplinsky, who in (howling accused Bohdan of treason and relations with Tatars. Khmelnitsky was preparing for an uprising or not - is unknown, but he was arrested by order of the crown hetman Pototsky. He was arrested soon. Khmelnitsky was arrested. Soon Khmmelnitsky was arrested. to run, and 11 December 1647 he and his son arrived in Zaporizhzhya Sich, and from there went for help to the Crimea. The moment for the request was successful. The Crimean Khan was unhappy with Poland, as she inaccurately paid an annual “gift” that he paid off raids, and besides, the peninsula had a poor harvest and, as a result, livestock mortality. The Tatars were not averse to compensating for their losses by plundering during the war. Khan agreed to help Khmelnytsky and put at his disposal a detachment of four thousand soldiers under the command of Perekop Murza Tugay-Bey. So on one side of the barricades were sworn enemies - the Tatars and Cossacks, although there was no trust between the new allies. As a hostage, the Khmelnitsky Timosh remained in Bakhchisarai, and Tugay-beat in the Cossack camp guaranteed, that Khan will not hit Khmelnitsky in the back. 18 April 1648 Khmelnitsky arrived in the Sich and outlined the results of his trip to the Crimea. The people on the Sich received him with enthusiasm and chose the Zaporozhian troops as the Ataman's chief. Hetman Khmelnitsky was called only later. By the end of April, 1648, Khmelnitsky already had at his disposal ten thousand people (including the Tatars), with whom he was preparing to speak in a "campaign of revenge."

The news of the seizure of Zaporozhye by the rebels alarmed the Polish administration, and decided to strangle the uprising in the bud. The Poles quickly contracted their forces to fight the Cossacks, and at that time the entire population of Little Russia was preparing to join the Cossacks as soon as they appeared ...

Crown hetman Nikolai Pototsky sent forward the four thousandth avant-garde under the leadership of his son Stephen, and ordered the registered Cossacks to go to his aid. However, the registry at the first opportunity interrupted their Polish commanders and joined Khmelnitsky. The Poles, who were in the minority, tried to retreat, but were completely defeated.

Pototsky decided "to punish the rioters approximately" and, not doubting the victory, he moved towards Khmelnitsky. And he was ambushed near Korsun. In this battle, all the regular (quartz) army of the Commonwealth during peacetime perished - more than 30 thousand people. The hetmans Potocki and Kalinowski were sewn into captivity, and given to Tugay-Bey as payment for help. All Polish artillery and huge wagons went to the Cossacks as military booty. Immediately after these victories, the main forces of the Crimean Tatars, led by Islam-Giray Khan himself, arrived in Ukraine. Since there was no one to fight with (Khan was supposed to help Khmelnytsky near Korsun), the horde returned to the Crimea.

Pototsky decided "to punish the rioters approximately" and, not doubting the victory, he moved towards Khmelnitsky. And he was ambushed near Korsun. In this battle, all the regular (quartz) army of the Commonwealth during peacetime perished - more than 30 thousand people. The hetmans Potocki and Kalinowski were sewn into captivity, and given to Tugay-Bey as payment for help. All Polish artillery and huge wagons went to the Cossacks as military booty. Immediately after these victories, the main forces of the Crimean Tatars, led by Islam-Giray Khan himself, arrived in Ukraine. Since there was no one to fight with (Khan was supposed to help Khmelnytsky near Korsun), the horde returned to the Crimea. News of the two defeats of the Poles quickly spread all over Little Russia. Peasants and commoners began to join the Khmelnytsky mass in masses, or, forming partisan detachments, themselves smash the estates of the Poles, seize towns and castles with Polish garrisons. Peasants and citizens tried with all cruelty to avenge the Poles and Jews for oppression, which lasted for many years.

The largest tycoon of the Left Bank, Prince Jeremiah of Vishnevetsky, having learned about the Khmelnytsky uprising, gathered his own army to help Hetman Potocki to pacify the uprising. If he had had time, then perhaps Khmelnitsky would have been defeated, but the frantic Jeremiah was late. Now he could only save his fellow tribesmen. Everyone who was somehow connected with Poland and its social system, went along with Vishnevetsky. The gentry, tenants, Jews, Catholics, Uniates knew that if they only fell into the hands of the rebels, they would not be spared. As shown storythey were not mistaken. Caught Jews, the Cossacks were executed with extreme cruelty. The rebels did not stand on ceremony with the Poles, especially with priests. As a result of this spontaneous pogrom on the Left Bank, within a few weeks of the summer of 1648, all Poles, Jews, Catholics, as well as those of the few Orthodox gentry who sympathized with the Poles and collaborated with them, disappeared. The following facts testify to the intensity of hatred: at least half of the Ukrainian Jews of the total number, estimated at approximately 60 000, were used by slaves or slaves. The Jewish chronicler Nathan G -over wrote: “From one [of the captured Jews], the Cossacks were skinned alive, and the body was thrown to dogs; others were badly wounded, but not finished off, but thrown into the street, slowly dying; many were buried alive. Nursing babies were cut in the arms of mothers, and many were cut into pieces, like fish. Pregnant women were ripped off their stomachs, took out the fruit and whipped them over the mother's face, and other people sewed a live cat into the ragged stomach and chopped off miserable hands so that they could not pull it out. Other children were pierced with a spear, roasted on the fire and brought to their mothers so that they could taste their meat ... "

Suddenly, Khmelnitsky tried to distance himself from the general popular uprising. He gathered the Cossack Council, from which he was able to get the start of negotiations with the Poles. However, the Poles used negotiations only to gain time to prepare a new army. True, the Cossacks had been sent ombudsmen for negotiations, but they had to make obviously impossible demands (issuing weaponstaken from the Poles, the issuance of the leaders of the Cossack detachments, the removal of the Tatars). The Rada on which these conditions were read was strongly annoyed against Bohdan Khmelnytsky for his slowness and for negotiations. Yielding to the demands of ordinary rebels, Khmelnitsky began to move to Volyn, where the Polish army was stationed. 21 September two armies met near Pilyavtsy. The Poles once again could not resist and ran.

In October, 1648, the year Bogdan Khmelnitsky laid siege to Lviv. As his actions show, he did not intend to occupy the city, limiting himself to taking strong points on its approaches: the fortified monasteries of St. Lazarus, St. Magdalena, the Cathedral of St. Jura. However, Khmelnitsky allowed detachments of rebel peasants, led by Maxim Krivonos, to storm the High Castle. The rebels seized the Polish castle, killing all its defenders, after which they demanded that the citizens pay Khmelnytsky a huge ransom for retreating from the walls of Lviv. After receiving the money, Khmelnitsky refused to march on Warsaw and led his army back to Little Russia.

This decision literally saved Rzeczpospolita: after all, after the victorious 1648 campaign of the year, the Cossacks would not have met with organized resistance from the Poles. Khmelnitsky could move directly to Warsaw and probably would have taken the defenseless Polish capital.

Why did the hetman not decide to ruin Warsaw? Yes, because psychologically it was his capital! For half a century, he faithfully served the Polish kings. It was in Warsaw that he traveled with the deputations of the Zaporozhian army, it was from here that the salary of the Cossacks came and orders came. After all, even raising a rebellion, Khmelnitsky sought to give it the appearance of some kind of legality! He constantly reminded that the rebel of the Cossacks, with the consent of King Vladislav himself. He, after voicing complaints from Cossack envoys in Warsaw to the nobility, allegedly asked: "Do you have no sabers?" That is, at that time Khmelnitsky was not thinking of any independence of Ukraine, much less about the transition of Little Russia under the scepter of Moscow state .

Here it is necessary to make a digression and carefully figure out who and for what took up arms in 1648.

Shlyakhta fought for its right to oppress the peasants and live comfortably through the conquered Little Russian population.

Tatars participated in the Khmelnytsky campaigns for two reasons. Firstly, for the sake of booty, and secondly, both the Cossacks and the Poles were enemies of the Crimean Khanate and, helping one or the other side, Islam-Girey weakened their strategic opponents.

In turn, for Bogdan, the Crimean Tatars were a real find: after all, he had practically no own cavalry. Horde also were born riders. In addition, the Tatars became the personal guard of the hetman, ready, if necessary, to fight not only against the Poles, but also to suppress the speeches of Hop opponents from among the Cossacks. (So special security-punitive units from Latvian riflemen and Chinese infantry, as you see, are not a Bolshevik invention at all!)

The peasants became the most numerous and most irreconcilable part of Bogdan’s army. They avenged their longstanding oppression, persecution of faith. Their main goal was to save Little Russia from the Polish yoke, and they had little interest in political squabbles. Numerous, selfless, but practically unarmed, and most importantly - untrained to the military cause, they had no chance to cope in open battle with the gentry, who had been preparing for war since childhood.

But the last group of rebels, the Cossacks, was not inferior to the gentry either in training or in the arsenal. Despite their relative small size, the Cossacks played a leading role in the uprising. They became the leaders of the rebel detachments, developed plans of operations, led the fighting and were the striking force in the battles. That is, in modern terms, the Cossacks were an officer corps and special forces in the army of Bogdan. And their goals were markedly different from those of the peasants. The Cossacks did not want the release of Little Russia from the power of the king and the nobility: they just wanted to become a gentry.

The Zaporozhian Cossacks completely satisfied the Polish social system - they were not satisfied only with their own place in it. The main requirements of the Cossacks were an increase in the registry and recognition of their gentry rights. The uprising was a kind of labor dispute - let us remember that the gentry had a legal (!) Right to defend their rights in arms. The logic of the Cossacks is unpretentious: "Take us to your service - we will not rebel, you will not take - we will rob you a little bit." And since the Cossacks perceived their actions solely as bargaining with the central government in Warsaw, they did not seek to destroy Polish statehood. Such sentiments were especially strong for the elders, who dreamed of taking places in the ranks of the magnates, subordinating whole regions to their power and forcing the peasants to bend their backs on them. In general, the Cossacks, long before Khmelnitsky, tried to get some area to feed. Likewise, in the dashing nineties of the twentieth century, frade-racquerers tried to take control of enterprises and entire industries. In the sixteenth century, the Cossacks tried several times to subdue Wallachia, putting their henchman on her throne. In the middle of the seventeenth, the Cossacks were incredibly lucky: fate gave them into the hands of all Little Russia, purified by the peasant war of the Polish yoke. It turned out that to conquer this region is easier than to achieve entry into the ranks of the noble class of the Commonwealth.

Near Lvov, the difference was revealed between the aspirations of the Cossacks and peasants, who were ready to go to Warsaw and complete their liberation. The same was repeated as in all previous uprisings led by the Cossacks: the betrayal of men in the name of specific Cossack interests. Even before reaching Kiev, Khmelnitsky issued a decree-wagon to the nobility, which confirmed their right to ownership of serfs. In Kiev, Khmelnitsky met with Polish ambassadors, who brought him a royal charter to the hetman. Khmelnitsky accepted the hetman's “dignity” and thanked the king for the honor rendered to him. This caused great irritation in the army, which is why Khmelnitsky, in his negotiations with the commissioners, behaved rather evasively. As a result, the negotiations did not lead to anything, and the Polish Sejm decided to gather gentry militia to fight the rebels.

In the spring of 1649, Polish forces began to concentrate on Volyn. Khmelnitsky, united with the Crimean Khan, laid siege to Zbarazh, where there was a large Polish detachment. King Jan Casimir himself led the twenty-thousandth army to the besieged. Under Zborov 5 August royal forces were attacked by rebels. The Poles were clearly losing the battle, because the Tatars and the Cossacks had already broken into their camp and carried out a wild slaughter. A little more - and the king himself would have been hacked to death by the Cossacks or captured. But Khmelnitsky suddenly stopped the battle, saving Jan Casimir from captivity, and the rest of the Poles from complete extermination.

The next day, negotiations began and the so-called Zborovsky Treaty was signed, crossing out all the successes of the rebels. Under this treaty, Little Russia remained under Polish rule, the lords returned to their possessions, and the peasants were obliged to serve them, as before the uprising. But the Cossacks received a huge benefit - the roster increased to forty thousand people who were endowed with land, the right to have two assistants. Personally, Khmelnytsky departed all Chigirinskoe eldership, bringing 200 000 thalers of income per year. Other Cossack leaders did not remain offended. But not included in the registry again enslaved. In fact, the Cossack officers and the hetman personally betrayed the rebels for the sake of selfish interests.

Soon, in full accordance with the content of the Zborovsky treaty, the Polish gentry began to return to Little Russia, accompanied by military detachments. One of them was the gentleman Koretsky, who previously owned huge estates in Volyn. However, local peasants in a bloody battle defeated the army Koretsky. Suddenly, Khmelnitsky suggested that the Volyn peasants voluntarily submit to the gentry, and then cruelly dealt with recalcitrant farmers. Many peasants died a horrible death: on the orders of the hetman they were impaled.

But even such a turn of fate did not force the Russian people, who had already dined freedom, to submit. The nobles could only return to their estates with the help of fire and a sword. And Khmelnitsky with the Cossacks actively helped them. So from the revolutionary leader hetman Bogdan turned into a traitor to the people.

The reaction of the common people was also quite natural: in the Zaporozhian Sich, a rebellion broke out against the Hop's father. The Cossacks elected the radical Cossack Jacob Khudoliya, an irreconcilable enemy of the Commonwealth, as their new hetman. A wave of anti-Polish speeches swept through the cities and towns, one of the biggest was the uprising of the inhabitants of the town of Kalnik. In response, Khmelnitsky in September 1650 published his decree providing for the death penalty for participating in various riots and insurrections. He sent a large punitive detachment to the Zaporozhian Sich, which quickly pacified the Cossacks. Khudoliy was executed in the hetman's capital Chigirin. Just as quickly, the hetman's troops liquidated a popular uprising in Kalnik, where five of its leaders were publicly executed. Cossack officers received orders from the “Hop's Hop” to suppress popular demonstrations by any means ...

However, even this did not satisfy the Polish nobility. Despite all the efforts of the king, the Zborovsky treaty was not approved by the Sejm, which decided to resume the war with the Cossacks. In the winter of 1651, hostilities began.

The situation Khmelnitsky became quite difficult. His popularity has fallen significantly, the common people did not trust the hetman. In search of help, Khmelnitsky agreed to recognize the primacy of the Turkish Sultan, who ordered the Crimean Khan to help Khmelnytsky as a vassal of the Turkish empire. 19 June 1651, the Cossack-Tatar army came together with the Polish under Berestechko. This battle is considered one of the largest in medieval European history - up to 1 5 0 thousands of warriors from each side participated in it. Despite the fact that among the Polish troops were the king himself and the crown hetman Pototsky, who was redeemed from the Tatar captivity, the real leader of the Poles was Prince Jeremiah (Yarem) Vishnevets. A descendant of the richest Russian princely family, Jeremiah in his youth became Catholic and became one of the eminent statesmen of the Commonwealth. For his cruelty to the rebels, he earned the nickname “Cossack Terror”, and for courage and good luck, love and selfless devotion to his warriors. In the three-day battle, Khmelnitsky was defeated, and Prince Jeremiah played a decisive role in this victory of the Polish weapon. He personally led his warriors to the attack. The Tatars, who constituted up to a third of the Cossack army, suffered great losses and began to hastily retreat. Khmelnitsky, leaving the Cossacks and peasants defending their camp, rushed to the Khan, seeking to return the Tatars to the battlefield. However, those weary of three-day bloody battles, refused to continue the battle, especially since it rained, the earth became soaked and they lost their main trump card - maneuverability.

In general, the Tatars have not returned. Bogdan did not return to his perishing army either. Some historians believe that he became a captive of Khan, others argue that he fled from his own colonels, hiding under the protection of Tatar sabers. One of the brightest contemporary Ukrainian historians and publicists Oles Buzin adheres to this version. In his book, The Secret History of Ukraine, he describes this moment as follows:

"But with what was now return Khmelnitsky? With bare hands? Zaporozhye hetman knew what to start after his return. Any creature from the camp will run over to the Poles and tell you that the hetman came without Tatars. And the king will send parliamentarians with a well-known proposal: forgiveness of revolt in exchange for the extradition of Bogdan. And the Cossacks will agree! They always agreed! And in 1596, in Solonitsa, when Nalyvayko was issued for the battle. And in 1635, when they sold Sulimu. And in 1637, under Borovitsa, he shoved off Pavlyuk. To sell hetmans is a favorite occupation of Zaporozhye "lytsars" who blew into political cards. Khmelnitsky knew about it not from books. In the end, he himself (then still a troop clerk) signed the capitulation at Borovitsa - in a simple way, “sell” Pavlyu-ka. Let the historians of the future smoke incense to fearless Cossa whose heroes. Khmelnitsky saw firsthand these half-drunk Orthodox Orthodoxy — he was one of them. To be in Pavlyuk's place and give your beloved bull neck under the sword of Warsaw in Lacha? And here you are!

The fact that the most astute of his contemporaries understood what had happened proves the diary of the participant in the battle of Bere with the Polish gentry Auschwitz: “Hop, seeing what is going on, that the camp with its troops was already under siege, and the hay did not get out, except by issuing he (Khmelnytsky. - O. B.), if he remained in the camp, hurried after Khan with Vyhovsky, his adviser, prudently saving his life and freedom. The reason was that he was chasing after Khan, in order to entreat him to return .. Only by reason to unscrew from the Cossacks and servility, taken in the blockade. Otherwise, they would not have let him out and would have willingly bought their lives with his head if he had not fooled them ... ”

Anyway, Khmelnitsky spent the whole month together with the Tatars. The besieged Cossack camp was protected on three sides by fortifications, and on the fourth an impassable swamp adjoined it. For ten days the rebels, who had chosen Colonel Bohun as their new leader, bravely fought off the Poles. To get out of the environment, we began to build dams through the swamp. On the night of June 29, Bohun began to cross the marsh with an army. As always, the Cossacks first of all took care of themselves: Cossack units and artillery secretly crossed the swamp first, leaving some peasants in the camp. When in the morning they found out that the Cossacks had abandoned them, the crowd, frantic with fear, rushed to the dams that they could not stand. A lot of people drowned. At the same time, realizing what was the matter, the Poles broke into the camp and killed those who did not have time to escape.

Then the Polish army, devastating everything on the way, moved to Little Russia. In addition to the main Polish troops, the Lithuanian hetman Radziwill also took part in the campaign. He defeated Chernihiv Colonel Nebabu, took Lyubech, Chernihiv, and then Kiev, after which the Polish and Lithuanian troops met near the White Church. At this time, Khmelnitsky is located near the town of Pavoloch. Here Cossack colonels began to flock to him with the remnants of their detachments. All were disheartened. The people belonged to Khmelnitsky with extreme distrust and blamed him for the defeat. But still he managed to keep the rebels in obedience.

Seeing his unenviable position, Bogdan began peace negotiations with the Poles. September 17 1651 was signed the so-called Belotserkovsky treaty, very unprofitable for the Cossacks. Under the new agreements, the registry was reduced, the nobility reaffirmed its right to restore all the old privileges, the Cossacks themselves should live only in the Kyiv region, and, in addition, the contract provided for the stay of Polish troops in Ukraine. The new treaty with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth caused even greater bitterness among the peasants and Cossacks than the Zborovsky agreement. When Khmelnitsky publicly announced its contents in Belaya Tserkov, an angry mob of Cossacks moved on him ... Fearing highly probable moles, the hetman, his retinue and Polish diplomats who were with him were forced to flee and seek shelter in the White Church castle. The royal diplomats, believing that Khmelnitsky himself was not long to live, tried to escape, but were caught by one of the rebellious Cossack detachments ... It is hard to say what fate awaited the Poles and Khmelnitsky, if not the troops loyal to the hetman. The Belotserkov revolt was crushed, its leaders were publicly executed by Bogdan. In addition, according to his orders, about a hundred Cossacks from the detachment that captured the royal envoys were shot.

However, despite the cruel punitive measures, the uprising could not be pacified. The people fought at once against two enemies - the Polish gentry and the “traitor Khmelnitsky”. People's speeches reached their peak in the spring of 1652, actually threatening to overthrow the Hetman government. In the Ukraine at that time acted a number of no one subordinate atamans. Zaporozhets Sulima, under whose command gathered up to ten thousand people, proposed to overthrow Khmelnitsky and transfer the hetman's mace to his eldest son - Timothy-Timis. The rebels tried to unite their troops and march on Chigirin, but the hetman's troops defeated them. Across the country did not stop fighting individual detachments Khmelnitsky, gentry and rebels. Later Bogdan once again tamed and rebellious Zaporizhian Sich, sending large punitive forces there. From this struggle of all against all, the common people began to flee en masse on the territory of the modern Kharkiv and Voronezh regions, which were then part of Tsarist Russia.

Vast territories plunged into anarchy. The Poles, who formally had peace, continued military actions against the rebels. In the spring of 1653, the Polish squad under the leadership of Charnetsky began to devastate Podolia. In order not to completely lose power, Khmelnitsky spoke in alliance with the Tatars against him. But the Poles managed to conclude an agreement with the Khan, according to which the horde was allowed to devastate the Orthodox lands of the Commonwealth.

Realizing that the Poles will sooner or later be able to restore their power over the whole Little Russia, Khmelnitsky began to persistently ask the Russian tsar to accept the Cossacks as an allegiance. Contrary to popular belief, Moscow was not at all eager to take Little Russia under its wing. She denied this to the Kiev Metropolitan Iov Boretsky in 1625, she was in no hurry to meet Khmelnitsky. Yet 1 of October 1653 was convened by the Zemsky Sobor, at which the question of accepting Bohdan Khmelnytsky with the Zaporozhian army into Moscow citizenship was resolved. Then the boyar Vasily Buturlin was sent to Pereyaslavl (there is also the writing of Pereyaslav). In this city were to gather representatives of all layers of the Little Russian people on the parliament. Along the way, the Russian ambassadors were greeted with bread and salt. Finally, 8 January 1654 was collected Rada, which Bogdan opened with the words: “For six years we have been living without a sovereign, in incessant curses and bloodshed with our persecutors and enemies, who want to eradicate the church of God, so that the Russian name is not remembered in our land .. Then the hetman invited the people to choose a monarch from among the rulers of four neighboring countries: Poland, Turkey, the Crimean Khanate and the Moscow kingdom. The people in response shouted: “Volim (that is, we wish) under the tsar of Moscow”! Pereyaslavsky Colonel Pavel Teteria began to go around the circle, asking: “Do you all so deign?” The participants answered: “Everything is unanimous!”

However, among the Cossack officers there were also opponents of joining Moscow. The most striking of them were Bohun and Sirko, who did not want to submit to any centralized authority in general. Moreover, in the Moscow kingdom the nobility did not have even a hundredth part of those rights and liberties that the Polish gentry possessed. But to speak openly against the king meant to be torn apart by many thousands of common people. After all, what did reunion with the Moscow kingdom mean for a simple Cossack? This meant that as soon as a hillock with whistles and shouts of “Allah!” Appeared, the Tatars would appear and the ataman would command: “To battle!”, The military men will shoulder shoulder to shoulder with the Cossacks. And steppe dwellers, except for Cossack peaks, will experience the deadly fire of Moscow archers and dragoon sabers. Which of the simple Cossacks will object to this? But for the hetman and the foreman, this meant that a boyar would come to them and check where the state funds were spent. In addition, any offended foreman will be able to complain to Moscow about injustice, and even the hetman will have to answer to the royal envoys. The recognition of the power of the king meant the restriction of the will of the foreman by law. So Khmelnitsky and his entourage went to Moscow citizenship without enthusiasm. No wonder they tried to get from the king confirmation of their privileges and property rights. The foreman even tried to demand that the king, following the example of the Polish kings, swore to them. To this, Buturlin firmly stated that such a “Nicols did not happen and will not be in the future!”, And the Cossacks, as new subjects, had to unconditionally swear allegiance to the king and henceforth to obey the king’s will in everything. For the Russian people, the very possibility of first agreeing on something with the tsar, much less demanding anything from him, seemed blasphemous. The citizen was obliged to serve without waiting for awards, and the king could bestow on his mercy for his work. I emphasize: he could, but he was not obliged at all. It was a feature of the Moscow kingdom. In the West, the land was given to the noblemen as payment for their service, the prince in Russia, and then the king favored their servants so that they could serve. In Poland, the king was obliged to report to the Sejm, and anyone, even the most handsome, gentry could challenge the royal will. In the Moscow state, the tsar, being an autocratic ruler, was responsible for his actions only before God. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the king was inherently a hired manager, in Russia, the king was the father and master.

Naturally, the Cossack elite agreed to recognize the sovereignty of the Russian tsar only out of fear of the common people, which they used to contemptuously call mob, fearing the loss of power over the peasants, who had long ago seen in the Zaporozhye army not defenders, but ordinary "lords" who were ready for the same in any moment to sell their fellow tribesmen into Tatar captivity. In Pereyaslav, our ancestors before the cross and the Gospel made an oath promise of loyalty to the Russian autocrat, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. The sovereign was sworn in not as an abstract person, but as a symbol of Russian statehood. The oath was taken forever, for themselves and for all subsequent generations.

For several months, the royal boyars with the Cossack elder rode all the Little Russian cities, announcing to the population about the decision of the Council, and offered to swear an oath to Sovereign Alexei Mikhailovich. Those who refused were declared that they were free people and, having taken their property, could go to Polish lands. By its representative composition, the Pereyaslavskaya Rada was the most legitimate assembly in the history of Little Russia. Neither the election of hetmans, carried out only by a handful of Cossack elite, nor the notorious Central Rada, convened in 1917 by a pitiful handful of impostors, cannot be compared with the fullness of the national representation in Pereyaslavl.

After the Pereyaslav Rada, the king satisfied almost all the requests received to him. The Cossacks were saved, and its roster expanded to sixty thousand people; cities kept the Magdeburg Law; the clergy and gentry were affirmed the rights to all the estates under their authority; taxes collected in the Ukraine, remained in the custody of the hetman.

The transition of Little Russia in 1654, under the "high hand" of the king was crucial to the course of the war of liberation. With such a powerful ally, the Little Russians were no longer threatened with the full or partial restoration of Polish power. But instead of contradictions between the Polish gentry and the absolute majority of the people, others came between the lower strata of society and the new Cossack elite. This new elite, which came to the place of the Polish-gentry, was composed by the hetman himself and the Cossack officers loyal to him. At first, the foreman demanded "obedience" (fulfillment of natural duties) in relation to Orthodox monasteries from their former Polish-Lithuanian (serf) states. Then they began to make demands of “obedience” in relation to the senior, but not personally, but “to the rank”, that is, the population had to perform certain duties in relation to colonels, centurions, and esauls (while they occupied these positions that were elected). It was not easy to draw a strict distinction between “obedience to the rank” and “obedience”, and on this basis abuses began immediately. Many complaints have been preserved that individual foremen “obedience to rank” turn personal into “obedience”.

Bogdan made a lot of efforts to make his commanders large landowners. At the same time, Khmelnitsky did not forget, naturally, to himself. By joining the property of Polish magnates Potocki and Konetspolsky to his farm Sabotova, the hetman became one of the richest people of his time. Quickly feeling that they were the real masters of the situation, the Cossack officers began to torment the Cossack lower classes and peasants with various requisitions, which could not but lead to another increase in opposition sentiments, which intensified in particular at the end of 1 6 5 6 - the beginning of 1 6 5 7. then Zaporizhzhya Sich. The rebellious Cossacks were going to organize a campaign "against Chi-girin, against the hetman, against the clerk, against the colonels and against any other sergeant ..." However, in the spring of 1657, the Khmelnytsky troops suppressed this rebellion, executing all its leaders. This was the last punitive action of Hetman Bogdan Khmelnitsky, since he died three months later.

Information