Fight for the Caucasus. Late XVI - XVII centuries. Part of 2

In 1614-1615 Shah troops repeated campaign in Dagestan. However, they also did not succeed, and went to Derbent. Abbas did not accept defeat and continued to try to conquer the regions of the North Caucasus. Soon there was news that the Persian shah was collecting troops to conquer the lands of the Kumyks and Kabardian Circassians. Abbas boasted that he would reach the Black Sea and the Crimea. In 1614, the Shah ordered the Shamakhi khan Shikhnazar to prepare for the 12 campaign thousands of warriors. The Persians planned to seize the Russian fortress of Terki, plant the governor there and attach the land of the Kumyks to Shamakha and Derbent. Similar news greatly alarmed the local population. The Russian commanders from the Terek reported to Moscow that they had found "great fear" on the Kumyk princes and murz, and they were asking for help from the Russian kingdom. In Moscow, having learned about the plans of the Shah, they sent him a letter in which they demanded that the shah should not ruin his friendship with Russia, “not to enter the Kabardian and Kumyk lands,” since these territories belonged to the Russian Tsar.

Shah Abbas in relation to the North Caucasus really made strategic plans. Planning an attack on Dagestan, Abbas now wanted to send troops from eastern Georgia through North Ossetia and Kabarda. With the success of the offensive, he planned to build fortresses on the Terek and Koisu Rivers, leaving garrisons there. Thus, the Persian state had to consolidate in the northeastern part of the Caucasus. The Persians "carrots and sticks" were able to attract to their side one Kabardian princes - Mudar Alkasov, whose lands stretched to the Darial gorge. In 1614, the prince traveled to Abbas and returned with the “Shah people”, began work to strengthen the Caucasian road, so that Abbas troops could pass along it.

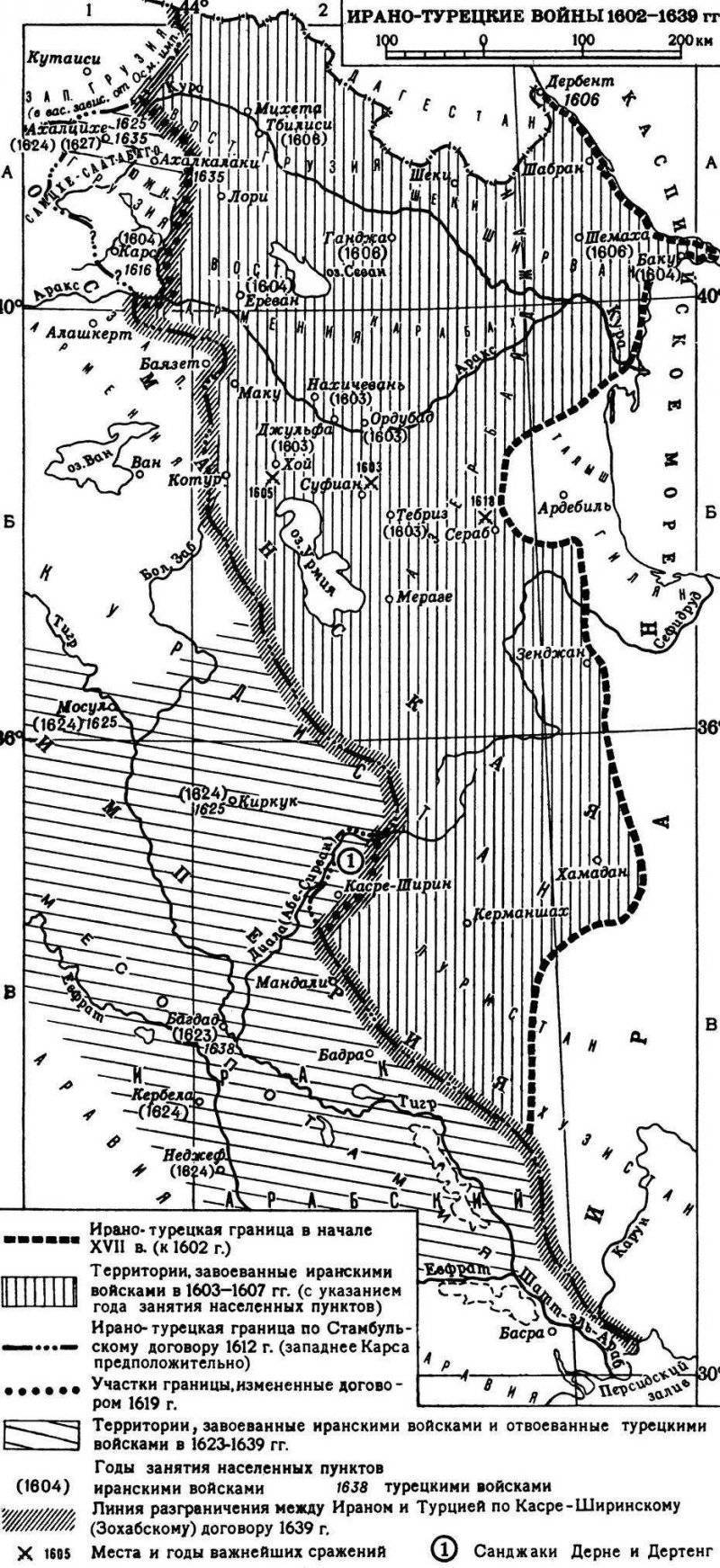

However, in 1616, the war of Turkey with Iran resumed, and for some time the break continued until 1639 (the 1616 — 1618 and 1623 — 1639 wars). Porta started the war trying to recapture the lost territory. In the autumn of 1616, the Turkish army unsuccessfully besieged Nakhichevan and Yerevan. In 1617, the Crimean detachments attacked Ganja and Julfa, and then, together with the Turkish army, approached Tabriz. However, 10 September 1618, the Turkish-Crimean army was defeated by Shah Abbas in the Serabi Valley. The Turkish government was forced to sign peace in 1619, giving Persia freedom of action in Kartli and Kakheti.

During the war, the Turks sought to enlist the support of mountain lords in order to open the way for the Crimean cavalry to the Caspian coast. Dear gifts were sent to Kabardian princes. However, the Crimean cavalry did not remove the Transcaucasus along the Caspian coast, since the path was closed by Russian fortifications on the Terek. The Turks had to transport Tatar troops from the Crimea to Georgia by ship. The Turks and the Crimean Khan continued their attempts to bribe Kabardian, Kumyk and Nogai feudal lords to attract them to fight Persia, but these actions were not very successful. The feudal lords gladly took gifts, but did not want to fight on the side of Turkey.

After the victory over Turkey, Abbas returned to his plans to conquer the Caucasus. He established control over Georgia and tried to subjugate Dagestan. Shah Abbas I forced the Kakhetian king Teimuraz I to send his mother and two sons to Iran as hostages (they were tortured), another son died in the war with the Persians. The Persian ruler twice with a large army invaded Georgian lands, the country was devastated, villages and churches were plundered, a significant part of the population was resettled. According to some information, up to 100 thousand inhabitants of Kakheti were killed and another 100 thousand were hijacked to Iran. Instead of them, up to 15 thousands of courtyards of the Azerbaijani "Tatars" were settled in Georgia, but soon the Georgians rebelled and killed all of them, not even sparing children. It should be noted that similar methods of warfare were characteristic of that time and region. Opponents regularly arranged acts of local genocide.

Abbas continued to pressure Dagestan. On his orders, the army of the Derbent lord entered the seaside Dagestan and forced Sultan-Mahmud Endireyevsky to recognize the authority of the Shah of Persia. In 1620-1622 under the decree of the Shah, the troops of his vassals of Derbent Barhudar Sultan and Shemakha Yusup Khan made a trip to the Samur Valley of Southern Dagestan, capturing the village of Akhty. However, the success of the Shah's forces could not be achieved.

Board of Sefi I

After the death of Abbas, the Persians continued their policy of expansion in the Caucasus. Sefi I, the grandson of Abbas (he killed the son, appointed his grandson as heir), reigned from 1629 to 1642 for the year, planned to build fortresses on Sunzha and Terek. Fortifications were going to be erected with the help of a detachment of Shagin-Giray, the local population and 15, thousands of legs of the Little Horde. In addition, the work was supposed to cover 10-thousand. Persian Corps. If necessary, it was supposed to send 40-thousand to the North Caucasus the army. However, these plans were not implemented. Almost all local rulers refused to support this project. In addition, the Persian state was busy with the war with Turkey, intense fighting took place in Mesopotamia and Georgia. This linked the main Persian forces, for the war in the North Caucasus there were no significant forces. The war in the South Caucasus was accompanied by the extermination and the hijacking of the local population, unrestrained robbery. The Iranian-Turkish war ended in 1639 with the signing of the Qasr-Shirin (Zohab) treaty, which confirmed the conditions of the 1612 peace of the year, that is, the Persians had to abandon their conquests in Iraq, but they retained the previously occupied territories in Transcaucasia. After this war, peace was established for a long period between the two great powers, since the forces were approximately equal, and the resumption of hostilities seemed hopeless to both governments.

Having completed the war with the Ottoman Empire, Sefi was able to return to the problem of seizing the North Caucasus. This prompted the Dagestan rulers to seek help from the Russian kingdom. The capture of Dagestan by the Persians was not in the interests of Moscow. In 1642, Shah's Ambassador Adzhibek in the Ambassadorial Order was officially informed that "it is necessary for Royal Majesty himself that Kois and Turks should supply cities, because that is the land of Royal Majesty." Sefi could not realize his plans to seize Dagestan, in 1642, he died from drunkenness.

Abbas II Board (1642 - 1667)

Son Sefi continued the policy of his predecessors, trying to implement what they failed. Abbas II was the second to change tactics and from open invasions, he switched to a change of certain objectionable masters. In 1645, a detachment of Shah's troops entered Kaitag and displaced the local feudal lord, utsmy. The origin of this word is unclear: according to one version it comes from the Arabic word “ismi” - “eminent”, on the other - from the Jewish word “otsulo”, meaning “strong, powerful”. It must be said that Kaytag utsmiystvo was considered one of the most influential Kumyk-Dargin feudal possessions of Dagestan in the 16th — 17th centuries. Utsmy Rustam Khan was not going to surrender without a fight, he gathered his supporters and defeated the Persians, pushing them out of their possessions. The enraged Shah Abbas sent a more numerous detachment to Kaytag Utsmiystvo, the Persians again occupied the mountainous region and expelled Rustam Khan. In his place, Amir Khan Sultan, loyal to Persia, was seated. The Persians planned to establish themselves in the province, building a fortress there.

These events forced the Dagestan feudal lords to turn for help to the Russian kingdom. They understood that separately, they have no chance to resist the mighty Persia. Andireevsky Vladyka Kazanalip wrote to the sovereign Alexey Mikhailovich: “Yaz (c) Kyzylbashsky and the Crimea, I don’t refer to the Turks, your sovereign is a slave direct. Yes, I beat you with your brow, the great sovereign: they would only tell me to push Kizylbashen, or our other enemies, to attack us, and you, the great sovereign, would tell me to give aid to the Astrakhan and Terek military men and Big Nagai to help. ” Moscow sent additional military forces to the Terek. At the same time, the Shah of Persia was demanded to withdraw its troops from Dagestan. Abbas did not dare to bring the matter to war with Moscow and withdrew his forces from the North Caucasus. This markedly strengthened the authority of the Russian kingdom among the Dagestan rulers.

Even the Persian appointee Amir Shah gave the terrible governor words about loyalty to the Russian sovereign. He wrote to Turki, that "there will be under the kingdom of the tsar and the shah Abbasov of Majesty with his hand in the slavery 's hands". Utsmiy also said that if the shah allows, he is ready to take the oath of Moscow on behalf of all the possessions in order to be under the royal arm in "eternal relentless servility to his death." True, it is clear that such vows and assurances cost little. The royal governors and the imperial generals quickly learned the lesson that in the East they give oaths easily (including on the Koran), but they also break them easily. In the Caucasus and the East (and throughout the world), force and political will were the most prized.

In the Iranian capital - Isfahan (became the capital under Shah Abbas I) did not accept this defeat, and did not intend to abandon plans for the conquest of Dagestan and the entire North Caucasus. Persia was at the top of its military and political power and was not going to retreat. The Persians began to prepare a new campaign in the North Caucasus. The hike took place in 1651-1652. In addition to the Persian detachments, troops from Shemakha and Derbent took part in it. Utsmiy Amir-Khan Sultan, Shamkhal Surkhay and Kazanlip Endireevsky also joined the Persians under the threat of immediate reprisals. Having ruined the Kabardian lands, the multinational shah's army attempted to take Sunzhensky town, but failed. After this campaign, the Dagestan rulers, who had broken their vows to Moscow, had to explain their behavior. In the letter they explained that they went to war with the Kabardian princes, who also raided their possessions. The letter reported that they did not offend a single Russian.

Abbas II expressed his dissatisfaction with the failure of the march to the Sunzhensky town. It was decided to continue the offensive. By Derbent began to tighten the troops 8 Khans. On the captured territory, the Shah planned to build two powerful fortresses near Terkov and Salt Lake by local forces. Each fortress was supposed to be located on 6 thous. Warriors. The implementation of this plan could dramatically change the geopolitical situation in the region. In such a scenario, Russia was completely expelled from the North Caucasus, and the Persians received powerful outposts to control the region. However, this plan was not realized.

The Iranian Shah was forced to abandon direct campaigns and engage in "diplomacy." Persians tried to replace objectionable feudal lords with more docile, supported feudal civil strife. At the same time, firms (diplomas) were sent to Dagestan with recognition of the ownership rights of local rulers. Thus, the local owners formally became vassals of the Shah. The Iranian government sent expensive gifts.

Under Shah Soleiman Sefi (who ruled between 1666 and 1694 for years), Iran has not advanced in the North Caucasus. This ruler was weak, weak-willed, preferring alcohol and women, not military matters.

Shah Abbas II.

Russian policy. Relations with Georgia

Moscow, in spite of all the difficulties of the first three decades of the 17 century, retained Turkey. During the first Russian tsar from the Romanov dynasty, Dutch engineer Clausen was sent to Turki, who strengthened the fortifications. The second time the fortress was renovated under Alexey Mikhailovich in 1670, the fortification work was carried out under the direction of the Scottish colonel in the Russian service of Thomas Behley.

Virtually the only major military operation of the Russian troops in the North Caucasus in the 17 century was a campaign in 1625 in the year of Terkov's governor Golovin to Kabarda in order to suppress unrest that echoed the Troubles in Russia. Even in this difficult time, most of the Kabardian feudal lords remained loyal to the Russian state, more than once participating in joint campaigns against the Crimean Khanate.

In the 17 century, Daghestan’s aggravation to Russia was caused by the constant pressure of Persia. In 1610, the Tarkovsky owner with a number of Kumyk princes brought an oath to Russian citizenship in the fortress of Turki. But in the future, Shamkhala and other Dagestan rulers had to recognize the supreme power of the Shah of Persia. However, they are in this position. So, Shamkhal from 1614 to 1642 year sent 13 embassies to Moscow. Subjects of Moscow also became Kaytagsky utsmiy Rustam Khan.

In general, it must be said that in the 17 century, Russia advanced much less in the Caucasus than during the reign of Ivan the Terrible. Under Ivan Vasilyevich, strong friendly, dynastic, and religious and cultural ties were established with the North Caucasus and Georgia. It is clear that this weakening of positions was associated with a number of objective factors. Distemper and intervention greatly weakened Russia. Turkey and Iran took advantage of this, having subjugated the vast Caucasian lands, strongly undermined Christianity there, spreading Islam in the North Caucasus. As a result, only the extremely eastern part of the future Caucasian line remained behind Russia.

Relations with Georgia. The Georgians, oppressed by Persia and Turkey, were clearly to the Russian kingdom. In fact, in Moscow was their only hope for survival, the preservation of faith. They hoped for the patronage of a faithful, Orthodox Russia. The essence of their petitions at this time was expressed in the sentence: “But we don’t have hope for anyone except you ...”.

In 1616-1619 ties with Kakheti were restored. Teimuraz I was hoping for military assistance to Russia in the fight against Persia. 1623, another Georgian embassy headed by Archbishop Theodosius visited Russia. In 1635, Teimuraz sent an embassy to Moscow headed by Metropolitan Nikifor, asking for protection and military assistance. In 1639, Metropolitan Nikifor arrived in Moscow for the second time with a request for financial and military assistance. In 1642, the metropolitan, with the Russian ambassadors, Prince EF Myshetsky and clerk I. Klyucharyov, brought a patent on acceptance of the Iversk land under the protection of the Russian state.

In 1638, the king of Megrelia, Leon, sent a diploma with the ambassador, priest Gabriel Gegenava, where he asked for Russian citizenship for his people. In September 1651, the owner of Imereti kissed the cross of allegiance to the Russian sovereign. After that, an embassy led by Japaridze and Archimandrite Evdemon was sent to Moscow. 19 May 1653, Imereti Tsar Alexander III received a letter of appreciation from Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich about accepting Imeretia into Russian citizenship. At the beginning of 1657, citizens of the mountain regions of Eastern Georgia — Tusheti, Khevsureti, and Pshavi — asked for Russian citizenship: “... we implore you, beat us with your head, so that you can take us into your service and army. From today, we have accepted your citizenship. ” Georgia sought to unite with Russia and receive political, military, spiritual and material support from the Russians. True, there was a big “but”, Russia and the Georgian possessions then did not have a common border.

Information