Medieval ships and medieval miniatures

A typical Hanseatic cogg is what is depicted in this miniature from the manuscript “Roman de Brut; Edward III; Destruction of Rome; Firabras", 1325-1350. England. British Library, London

leaving it on the left and heading for Syria.

We landed at Tire,

because there is our ship

had to leave the cargo.

Acts of the Apostles, 21:3

History in medieval miniatures. It just so happened that the medieval miniaturists, drawing up their manuscripts, reflected in their illustrations almost all aspects of the life around them. And one of its important points was ... transport links between countries and individual cities.

It is clear that most people at that time traveled by land. But the attacks of robbers and the hardships of a long journey on bad roads were so great that there were many people who preferred to move and transport their goods by sea. In coastal areas, fishermen went out to sea, so the art of building boats and ships did not die at all after the collapse of the powerful Roman Empire and the death of the Western Roman Empire in 476.

True, maritime trade in the Mediterranean basin was then in decline. The former art of building magnificent sailing and rowing triremes and penthers has also been forgotten. Yes, they were, in general, now they are not needed. After all, who now opposed all the same Byzantium, which remained an outpost of civilization among the boundless sea of barbarian tribes that flooded Europe? The Slavs on their one-tree boats were dangerous only in their numbers. But the famous "Greek fire" was enough to fight them - a combustible mixture that continued to burn even on water. The Arabs, who annoyed the Byzantines a lot, also could not resist the "Greek fire", even if they already had ships with sails.

But in the north of Europe, and above all in Scandinavia, there were no land roads at all, and here ships became the main means of communication. It was in these places that the Normans lived - North Germanic tribes, excellent shipbuilders, sea pirates, warriors and merchants, who played an important role in the history of many states and peoples of Europe.

Thanks to the finds of archaeologists who dug up entire ships of the Viking leaders *, who for a long time kept the whole of Europe in fear, we know that the northerners built two types of ships at that time: combat ships - drakkars, called "long ships", and merchant ships - knorrs, smaller in size. sizes and shorter. Knorrs were in use throughout the Viking Age; during the settlement of Iceland, they could carry up to 30 tons of payload, and later, in the 50th century, the Norwegians went to Iceland already on knorrs with a payload of up to XNUMX tons.

On the first Viking drakkars, benches for rowers were not yet equipped. During the calm of the sea, they rowed with oars, sitting on their chests. The presence of a large sail gave these ships unprecedented speed for those times. Having met other people's ships at sea, the Vikings usually took them on board.

So swimming in the IX-XI centuries. along the coast of the North and Baltic seas was fraught with considerable danger, not to mention the fact that in their shallow-draft ships they even climbed up the Seine and kept Paris under siege for nine months! Well, then they completely conquered part of the coast from the French king, where they then founded their own duchy - Normandy and managed to get on their ships even to North America!

Here are just images of these "long ships" in miniatures in medieval manuscripts for some reason is not found. The only artifact where you can see them, and even at the stage of construction, is the "Bayeux tapestry", but historians were not lucky with their images in miniatures.

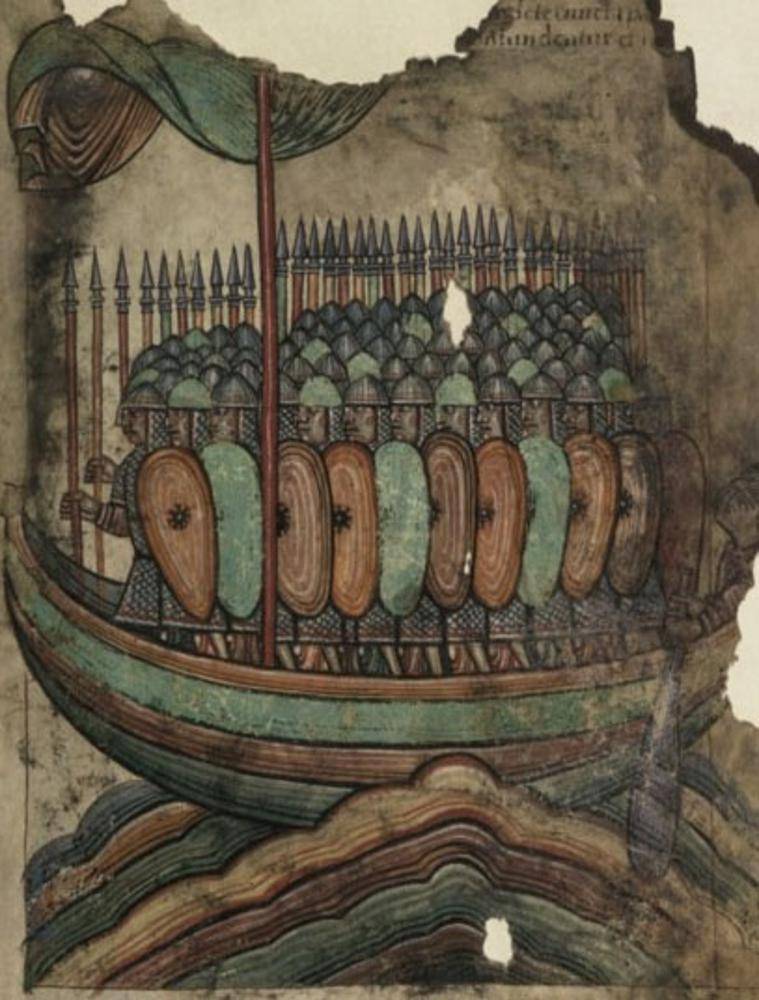

One of the earliest depictions of a medieval European ship full of warriors with almond-shaped shields, dated to 1000-1100 BC. Saint Aubin, France. National Library of France, Paris

But in the northern seas, by the XNUMXth century, drakkars had already ceased to swim. New ships appeared - pot-bellied, high-sided single-masted sailboats, which served primarily for the transport of goods. They were called "round ships" - coggs (from the ancient German luigg - round). They could not swim at high speed, but they carried a large load, which was required by the merchants, who were gradually strengthening their position. In addition, the design and rigging of the coggs was such that they provided these ships with excellent stability when they were heavily loaded.

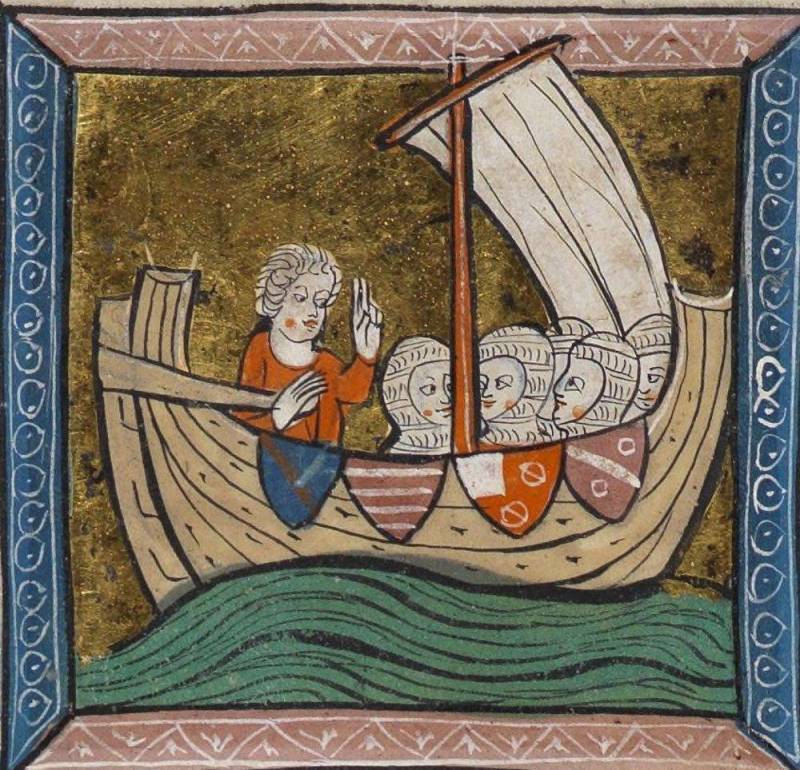

This miniature depicts a ship with the extremities decorated with various bird heads. However, it already has a trebuchet - a combat throwing machine. That is, the size of this vessel already allowed to install such weapons. "Romance of Alexander", 1250 St. Albans, England. Cambridge University Library

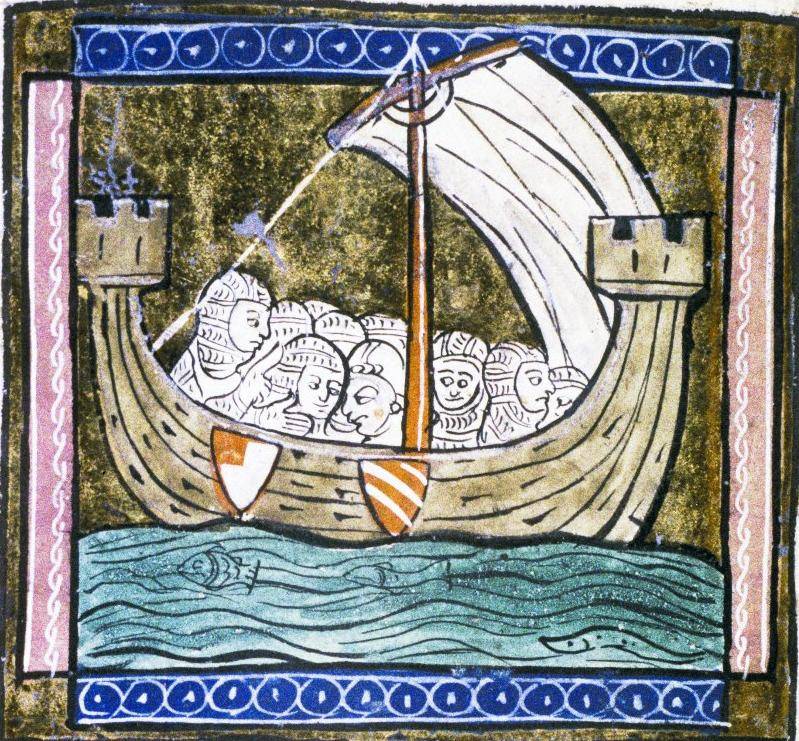

A characteristic feature of the North Sea coggs was tower-like platforms - castles ("castles") - on the bow and on the stern for archers. Moreover, ship castles were installed both on military and merchant ships. Exactly in the middle of the ship was a mast assembled from several logs. A special “barrel” was attached to the mast for observers and archers, equipped with a block system to lift ammunition up. Later, the “barrel” was structurally improved on karakkas and was called mars, which could accommodate up to 12 archers or crossbowmen.

An important technical achievement of the shipbuilders of Northern Europe was the rudder mounted on the rear stem and controlled by a tiller. Miniature from a manuscript from northern France, 1280–1290. National Library of France, Paris

Strong frames at a distance of 0,5 m from each other, oak plating 50 mm thick and a deck laid on beams - the transverse beams of the hull set, the ends of which were often brought out through the plating - these are the important features of these ships. The rudder was also a novelty, replacing in the 30th century the steering oar, which was located on the side of the board, and straight, strongly beveled to the keel line of the stems - the bow and stern ends of the vessel. The stem began to end with an inclined mast - a bowsprit, which served to stretch the sail in front. The largest length of the cogs of the Hanseatic Trade Union was approximately 20 m, the length along the waterline was 7,5 m, the width was 3 m, the draft was 500 m, and the carrying capacity was up to XNUMX tons.

The fact that tower-like superstructures-castles on the bow and stern already appeared on ships at that time is evidenced by many miniatures, and this one is one of them! "Lancelot Cycle" 1290-1300 France. Bodleian Library, Oxford University

It is interesting that many large ships of that time, as well as modern ferries and car carriers with horizontal unloading, were equipped with side ports that served to load and unload goods. This allowed them to take cargo on deck and at the same time unload the goods brought through the same port.

In the second half of the 300th century, two-masted, and later even three-masted coggs appeared. Their displacement was 500–28 tons. To protect themselves from pirates and enemy ships, Hansa merchant ships had on board crossbowmen and even several bombards, powerful artillery pieces for that time that fired stone cannonballs. The length of military coggs reached 8 m, width - 2,8 m, draft - 500 m, and displacement - XNUMX tons or more.

At the stern and in the bow of the commercial and military coggs, high superstructures were still located. In the Mediterranean, there were sometimes two-masted coggs with slanting sails. At the same time, despite all the improvements, coggs remained coastal ships - suitable for navigation only near the coast. Meanwhile, Europe needed more and more spices, and their flow through the ports of the Mediterranean began to dry up due to the fact that even before the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Turks captured all the coasts of Syria and Palestine, as well as North Africa, and began to interfere with European trade.

Miniatures depicting medieval Byzantine galleys with a ram on their bows have survived to our time. "Alexander's Tale", 1300-1350 Archives of the Hellenic Institute of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Studies in Venice

Byzantine galleys, known since the XNUMXth century, were warships with one or two rows of oars and one or two masts with oblique triangular sails. There were two steering oars, as before, and a ram protrusion was still preserved in the bow. However, now it was practically not used anymore, since the Byzantine galleys, in addition to traditional throwing machines, also had on board installations for launching their mysterious fire mixture - “Greek fire”. A lot of its recipes have come down to us, so it is difficult to say which of them the Byzantines themselves used. But its long and stable flammability (it could not be extinguished) is beyond doubt.

The main feature of both large and small ships of the Mediterranean were, as already noted, triangular, or “Latin”, sails: they created a “wing effect” and allowed them to move at an angle to the direction of the wind (up to 30 degrees relative to the axis of the vessel). Such a sail converts even the lightest breeze into useful thrust. The size of ships grew especially during the era of the Crusades of 1096-1270, when it was necessary to transport many heavily armed crusaders, soldiers and pilgrims from Europe to Palestine across the sea.

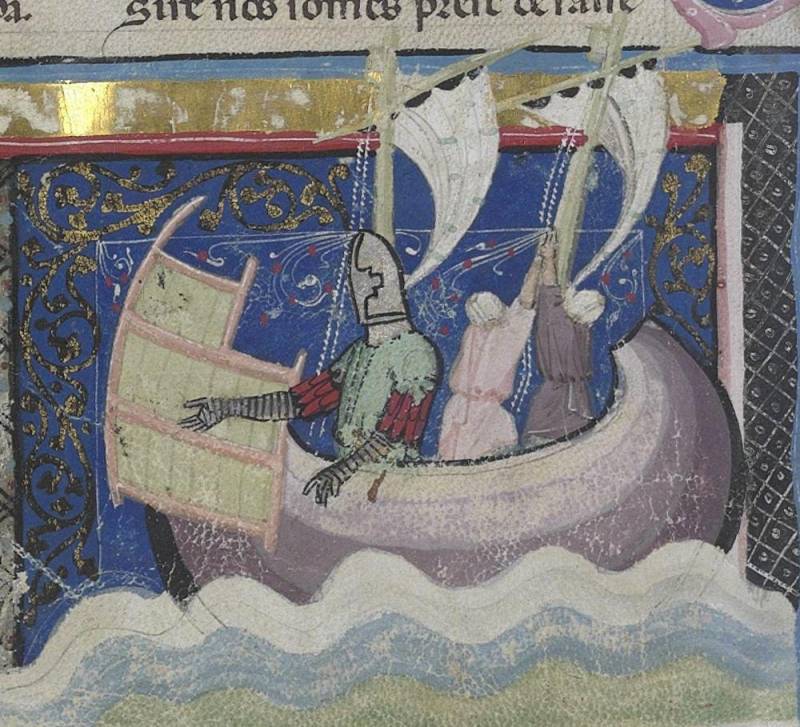

The Venetian nave is a ship of pilgrims and crusaders. "The Romance of Tristan", 1320-1330 Milan, Italy. National Library of France, Paris

The galleys, most of which were occupied by slave rowers chained to their benches, could not transport crusaders and pilgrims to Palestine. Therefore, Mediterranean shipbuilders began to build huge, clumsy, but very heavy-lifting naves. They had a sheathing, but Latin sails were used, and the hulls had residential superstructures for passengers rising 10–15 m above the water. In the stern there were two short and wide steering oars. The crew of the naves consisted of a committee with a silver whistle for giving commands; the patron who controlled the sails; a pilot plotting a course; two helmsmen and physically strong rowing galliots.

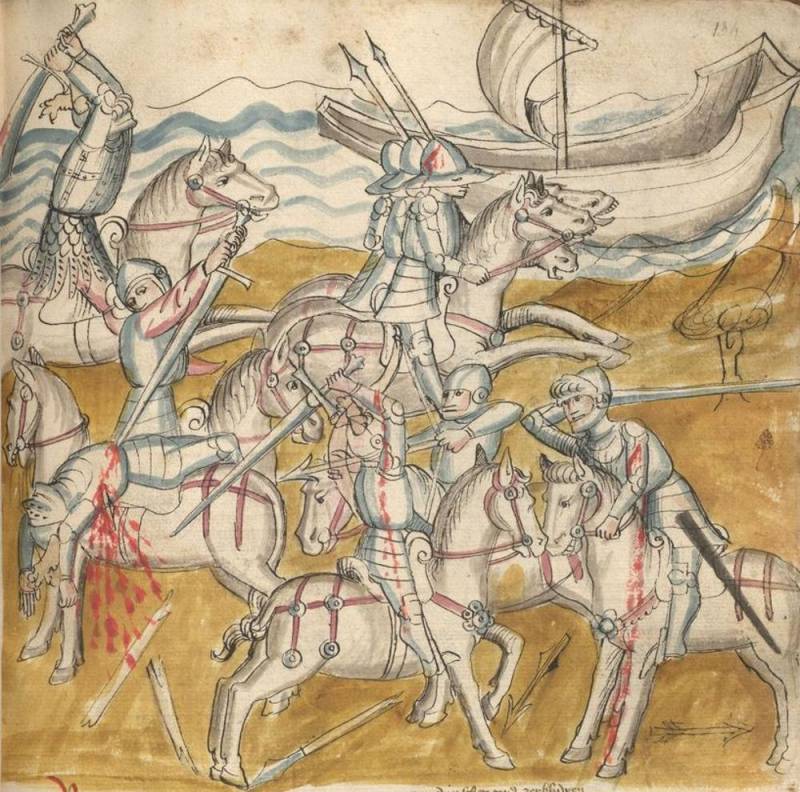

A naval battle allegedly taking place in ancient times "before Caesar". In fact, Mediterranean ships of the 1325th century are depicted here. Miniature from the manuscript "Ancient history before Caesar". 1359–XNUMX Naples, Italy. British Library, London

The voyage from Venice to Jaffa in Palestine lasted ten weeks. Pilgrims who have already visited the Holy Land recommended that those departing take with them their blanket, pillow, clean towels, a supply of wine and water, crackers, as well as a cage with birds, pork hams, smoked tongues and dried fish. On the ships, all this was given out, but, as the pilgrims said, linen and towels were stale, rancid crackers - hard as a stone, and even with larvae, spiders and worms; and the wine was more like vinegar. But more often they talked about the need to take incense with them, because on the decks in the heat there was an intolerable stench from horse manure, since horses and the feces of pilgrim passengers who suffered from seasickness were also transported on these ships. The decks were covered with sand, but it was raked out only upon arrival at the port.

On the approach to the island of Rhodes, shipbuilders could encounter pirates, from whom they often paid off. During the trip, there were cases of death of passengers from diseases. And yet, despite all the difficulties, voyages to the shores of the Middle East and Africa were made more and more often. During the journey, wealthy passengers allowed themselves luxurious meals and entertainment. They took with them pages, a butler and a valet, and even musicians who entertained them during meals. Along the way, the pilgrims landed on the island of Corfu, where they hunted goats. We also landed on other islands: to stretch our legs and rest.

Image of a Mediterranean ship with a steering oar and a "crow's nest" on the mast. Miniature from the manuscript "Ancient History before Caesar". 1325–1359 Naples, Italy. British Library, London

At the same time, very many ships in the Mediterranean were built with flat planking, in which the boards were tightly fitted with edges one to one, and did not overlap, as with the Vikings, on coggs and on Venetian naves. With this method of building a vessel, building material was saved, since half as many boards were required for the hull, and most importantly, ships with such plating were lighter and faster. New methods of construction, spreading throughout Europe, contributed to the emergence of new ships. In the first half of the XNUMXth century, the carakka became the largest European ship used for military and commercial purposes.

If you look closely at medieval illustrations with ships, it becomes obvious that the artists who painted them did not at all care about depicting them on a scale in relation to the figures of people, and indeed, they painted them as they wanted. In general, they are quite accurate in some details, but no more. Their role in miniatures is always subordinate to the people depicted. And here is one example of this approach: a miniature from the manuscript "The Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund", 1433-1434. Bury St Edmunds, England. British Library, London

An absolutely fantastic depiction of the characters of the Trojan War and ... an equally fantastic depiction of a ship. "History of the Trojan War", 1441 Germany. German National Museum, Nuremberg

One of the most realistic depictions of a ship. "The Conquest and Conquerors of the Canary Islands", 1405 Paris, France. Bodleian Library, Oxford University

She had developed superstructures at the bow and at the stern, covered from above with special roofs made of beams, on which fabric was pulled to protect against the sun, and a net to protect against boarding. She did not allow enemies to jump onto the deck from the superstructures of her ship and at the same time did not interfere with shooting at them. The sides of this ship were bent inward, which made boarding difficult.

The length of such a carrack could reach 35,8 m, width - 5,7 m, draft - 4,1 m, carrying capacity - 540 tons. The crew of the vessel: 80–90 people. Trade carracks had 10-12 cannons each, and the military ones could have up to 40! Such ships have already gone on long and long voyages. Later, according to the type of caracques and coggs with three masts and smooth plating, in Europe in the XNUMXth century they began to build caravels - ships of the era of the Great Geographical Discoveries.

"Battle of the Sluys". Miniature from the "Chronicle" by Jean Froissart, which contains, perhaps, the most realistic depictions of ships of the XNUMXth century. National Library of France, Paris

It is believed that the first ship of this kind was built by a French shipbuilder, Julian, at the shipyards of the Zuider Zee in Holland in 1470. The ships of Columbus "Pinta" and "Nina" were also caravels. But his flagship "Santa Maria" (in his notes he calls it "nao" - "big ship"), most likely, was a karakka, which means that it belonged to the same "round" ships.

* Where did the word "Viking" come from, scientists are still arguing. It is also translated as “children of the bays” - from the Norwegian word “vile” - “bay”, and from the Norman root, the meaning of which comes down to the Russian word “wander”. One way or another, we are talking about people who left their home and hearth for a long time and went on distant voyages under the guidance of their military leader - the king. It is possible that they were called Vikings if they wanted to talk about their characteristic way of life, and Normans when they emphasized that they belonged to the peoples of the North. After all, "Norman" in translation from Old Norse just means "northern man."

Information