"The people have the form of government they deserve": the French conservative Gustave Lebon and his concept of the struggle of peoples

It is generally accepted that conservatism was initially hostile to nationalist ideas, as it advocated the preservation of the political forms of the XNUMXth century. As you know, the terms “right” and “left” first appeared in the French National Assembly during the French Revolution, where opponents of the revolution, supporters of a constitutional monarchy, who wanted to preserve the status quo, sat on the right. Actually, the concepts of "conservative" and "liberal" also originated and entered into socio-political use in France.

However, a number of researchers are of the opinion that conservatism is a national phenomenon, as opposed to the international ideologies of liberalism and socialism, and therefore universal definitions of conservatism are difficult. In particular, French conservatism, and the views of Joseph de Maistre and François René de Chateaubriand confirm this, had a more traditionalist, religious-mystical bias. This opinion is justified, since the reality is that by the end of the XNUMXth century, many classics of European conservatism acted simultaneously as classics of nationalism. One of these representatives of the national conservative camp was the French sociologist Gustave Lebon.

In historiography, Lebon's heritage has been studied rather poorly. As the historian Aleksey Fenenko notes in his monograph “The National Idea of the French Conservatives of the 1970th Century”, until the early 2000s, Gustave Lebon’s works were of interest mainly as “desktop works” of the greatest dictators of the XNUMXth century. A similar approach also dominated Soviet historiography, where orthodox Marxist positions dominated in the analysis of the views of the French conservative (Lebon's works were not directly published under the USSR at all). In the XNUMXs, several works were published that deserve attention, but they cannot be called impartial.

However, can historiography be completely impartial? Gustave Lebon himself believed that no, and was skeptical about stories as science:

In essence, however, their real life is of little importance to us; we are interested in knowing these great men only as they were created by folk legend [1]."

In this material, we will try to analyze the philosophical and political views of Gustave Le Bon and his sociological studies, which still do not lose their relevance.

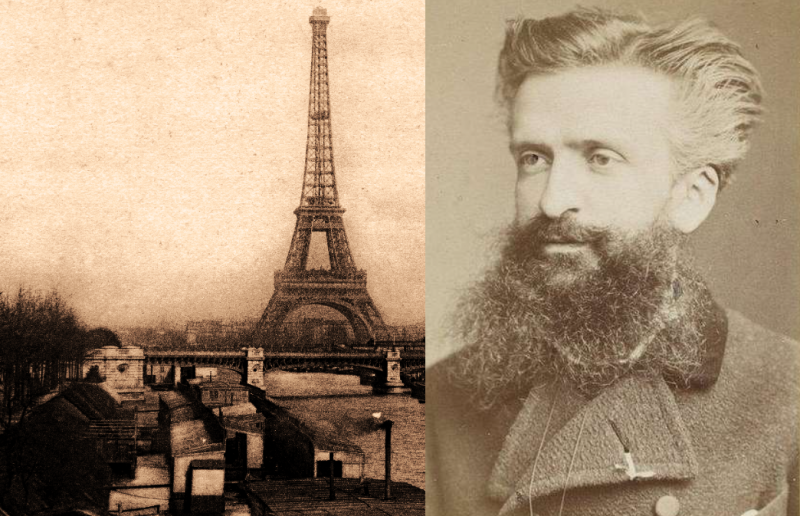

Scientific activity of Gustave Lebon and the formation of his views

Gustave Le Bon was born in 1841 in the town of Nogent-le-Rotrou, 100 km southwest of Paris. In Nogent-le-Rotrou, Gustave lived with his brother Georges and his parents for only 8 years, but there is a street named after him. The father of the family, Jean-Marie-Charles Lebon, was an official, his mother, Annette-Josephine, was a housewife [4]. They belonged to the middle class, had Breton and Burgundian roots, their coats of arms date back to 1698 [6].

After graduating from the classical lyceum, Gustav Lebon began to study medicine at the University of Paris. He received a good medical education, which allowed the scientist to subsequently develop his scientific knowledge in the field of anthropology and psychology. Having received a medical license, Lebon decided not to limit himself to treating patients, but to achieve academic heights and public recognition. It should be noted that the science of the second half of the 4th century was a vast field with many unplowed plots, and medical education was such that it could serve as a basis for research in anthropology, psychiatry and other disciplines [XNUMX].

The topic of the first publication of G. Lebon (1862) was the diseases of people living in swampy areas. Then he wrote several articles on fever and asphyxia, and his first large book, Obvious Death and Premature Burials (1866), seemed more than strange to physicians of that time, because the deceased is the deceased, everyone knew this, and even more so doctors. And Le Bon argued that many patients who were considered dead were actually not, and proposed methods for preserving and restoring life, a number of which practical medicine began to be considered only from the 70s of the XX century [4].

In The Psychology of the Generation, written at the very end of the 1860s, and in several other works on the medical subject, Le Bon perfected his style and gradually connected his scientific career with pathology and the diagnosis of diseases. It should be noted that, despite the diverse interests in various fields of knowledge, Lebon always considered them from a medical point of view.

At the same time, already in the 1860s, Le Bon began to expand the field of his diagnoses, including certain categories of French life, in particular, growing rates of alcohol consumption and falling birth rates. For Lebon, as well as for many thinking Frenchmen, the contrast when comparing similar indicators of France and Germany testified to the economic and demographic lagging behind of the republic [4].

The lag of France from Germany was clearly manifested during the Franco-Prussian war. Lebon, then living in Paris, voluntarily entered the medical service and organized a military ambulance department. As head physician, he oversaw the behavior of the military under the worst conditions. Armed with a practical knowledge of warfare, military discipline, and a study of the behavior of a person in a state of great stress, he wrote treatises on the leadership of military operations, which, having been approved by the generals, were studied in military academies. At the end of the war, Lebon received the title of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor [4].

Lebon witnessed not only the Franco-Prussian war, but also the Paris Commune. He saw how the revolutionaries burned the Tuileries Palace, the Louvre library, the city hall and the Renaissance theater, part of the Palace of Justice and other irreparable works of architecture. As the historian Nikolai Lepetukhin notes, these events strengthened his personal pessimism and strengthened his confidence in the decay of the French nation.

Gustave Lebon continued his journalistic activity, the combination of popular science and social commentary was his forte. Soon commercial success came to Lebon. Already by 1875 he was one of the few scientists who could live by publishing his work. At this time, Lebon especially enthusiastically delved into the problems of psychology and was actively engaged in anthropology, studying the cranial parameters of various human races. Gustave Lebon was greatly influenced by the scientific works on the theory of evolution of Ch. Darwin; they were for him, according to R. Nye, "the best substitute for religion, a reliable, conservative, practical, completely unwritten deity" [7].

Le Bon's most famous and best-selling work was The Psychology of Crowds (Psychology of Peoples and Masses, 1895) - 14 editions of it appeared in 1895 years (1909–14). In this work, the author considered two topics: racial psychology and mass psychology.

"Psychology of peoples and masses" - the fundamental work of the French sociologist

The book "Psychology of Peoples and Masses" ("Psychology of Crowds") not only had a great influence on the founders of social psychology and the first sociologists, but went beyond the academic environment - into the political and military spheres [5]. Le Bon is rightfully considered the founder of the sociology of the masses. He actually founded such an important area of modern socio-political research as the "sociology of mass communication" - the study of "institutions and characters of mass communication" and their interaction within the mass media [2].

"Psychology of peoples and masses" consists of two approximately equal books. The first book, The Psychology of Nations, is in fact an almost verbatim retelling of The Psychological Laws of the Evolution of Nations, which Le Bon had published a few years earlier. The second book of The Psychology of Crowds, the most valued in science, is called The Psychology of the Masses and consists of three sections (13 chapters).

Consider some of the main theses of this work.

First, the French sociologist pointed out that the life of a people, its institutions, beliefs and arts are only the visible products of its invisible soul, and in order for a people to transform its institutions, its beliefs and art, "it must first remake its soul." According to Lebon, the fate of the people is controlled to a much greater extent by the dead generations than by the living ones.

Lebon thought.

In his later work, The Psychology of Socialism (1898), the French sociologist puts forward his own concept of ethnic consciousness, which, from his point of view, is divided into two layers. The author considers the “innate ideas” of its members to be the unconditional support of the nation – “the inheritance of the race, bequeathed by distant or immediate ancestors, the inheritance perceived by a person at his very birth and directing his behavior [3]”. This is followed by a layer of “acquired or mental representations”, by which Le Bon understands those features that a person has acquired under the influence of his own social environment [2].

It is from the hereditary "innate ideas" that the character of a given people depends, that is, the reason why the republican institutions of the United States flourish, and the republics of Latin America are in a state of decline. The founder of the "sociology of the masses" sees the basis of human behavior not in social traditions, but in some kind of ethnic subconscious, bequeathed by the ancestors and not amenable to rational control [2]. We will return to this issue later.

Secondly, Le Bon, being an idealist, argues that the world is ruled by ideas, and the strong personalities who spread them play a huge role in history.

Whether it be a scientific, artistic, philosophical, religious, in a word, whatever idea, its dissemination is always carried out in the same way. It must first be accepted by a small number of apostles, to whom the strength of their faith, or the authority of their name, gives great prestige. They then act more by suggestion than by evidence [1]”,

Lebon says.

Le Bon notes that it is not inventors and theorists, but strong personalities and fanatics who carry the crowd with them, write history.

Similar thoughts were developed many years later by the German philosopher Oswald Spengler, in his "The Decline of the Western World", who noted that theorists' great delusion is that they believe that their place is at the top, and not in the train of great events.

Spengler wrote.

Gustave Lebon concludes:

Thirdly, the French sociologist makes important discoveries in the sociology of the masses. In particular, Le Bon has the expression "collective soul". He applies this concept to races, nations, nationalities and to the crowd that appears and disappears [9].

The gathering in such cases becomes what I would call, for lack of a better expression, an organized crowd or a spiritualized crowd, constituting a single being [1].

This comment links Le Bon's thoughts to the theory constructs of the Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, who writes about the same thing in a work on synchronicity. The ideas about the collective spirit and the influence of heredity on the cause of human behavior are obviously close to Jung's ideas about the archetypal composition of the collective unconscious (Jung believed that the collective unconscious is expressed through universal archetypes - signs, symbols or patterns of thinking or behavior inherited from our ancestors).

In his analysis of the feelings and morality of the crowd, Le Bon proceeds from the fact that it is controlled by the unconscious. The crowd does not reason, it does not have the ability to suppress its reflexes, it obeys the most diverse impulses from the most cruel bloodlust to absolute heroism, because it is under momentary excitement. Therefore, one of the properties of the crowd is its variability and impulsiveness. The crowd, by virtue of its large number, is aware of itself as powerful, does not tolerate objections and obstacles, moreover, feels itself unpunished.

Next, we will consider the concept of the struggle of races and civilizations, which follows from Gustave Le Bon's understanding of the national idea.

The concept of the struggle of races and peoples G. Lebon

As mentioned earlier, the French sociologist put forward his own concept of ethnic consciousness and believed that hereditary factors play a predominant role in the character of peoples. Thus, as A. Fenenko notes, he made a real revolution in the structure of the national idea and transformed the entire system of basic values of European political philosophy of the 2th century. In fact, within the framework of Lebon's sociology, "classical nationalism" was replaced by a new concept of "national-racial identity". In Lebon's sociological system, all state institutions are directly dependent on the "national spirit" [XNUMX].

Le Bon's national theory breaks completely with the traditions of Rousseau and the French Revolution. Political institutions - the basis of the national state in the political thought of the twentieth century - are given a secondary place in it. Speaking about the classification of peoples, the French researcher emphasizes that neither language, nor environment, nor “political groupings” can serve as its basis [2]. Only psychology can serve as such a basis, since it is precisely psychology that shows “that behind the institutions, arts, beliefs, political upheavals of every people there are certain moral and intellectual features from which its evolution follows” [1].

Analyzing the worldview of G. Lebon, one cannot but pay attention to the fact that in his works the concepts of “people” and even more so “nation” are used immeasurably less than the concept of “race”. Already in the pages of The Psychology of Crowds, he introduces two categories: "biological race", based on common anthropological characteristics; and "historical race", united only by common psychological features.

Le Bon's use of the concept of "historical race" shows his deep dependence on the previous layer of French nationalism and conservatism and gives his theory a completely unexpected perspective. In fact, the author of The Psychology of Peoples and Masses acted as the heir to a long tradition of historiography of the 2th century. Within its framework, the concept of "struggle of races" was the dominant leitmotif of the analysis of European history [XNUMX].

The theory of the "struggle of races", as the basis of all European history, originated in English socio-political thought in the middle of the 2th century and reached its peak in France during the Restoration. In those years, a tense controversy took place in French society about the outcome of the revolutionary events and the Napoleonic Wars [XNUMX].

In Lebon's works, the concepts of "nation" and "race" are by no means identical to each other. The French thinker does not deny the "national theory" of his predecessors: he only takes it to a qualitatively new stage, adding elements of irrationalism to it. The basis of his national theory is the irrational self-perception of the nation, inherent in all its members. Such a theory is close to the classical "national idea" of the French conservative Alexis de Tocqueville, although the focus is shifted from rational political institutions to irrational hereditary ideas.

Since representatives of different races live and think based on different values and norms, they inevitably come into conflict with each other: the wars that the races waged among themselves for centuries are due to the incompatibility of their characters. Different races cannot feel, think and act in the same way and therefore cannot understand each other [5].

The struggle between the races, and not their illusory agreement, has always been the predominant fact in history. Peoples were in constant struggle, and from the beginning of the world the right of the strong was always the only arbiter of their destinies. The laws of nature cannot be changed by man, they operate with the blind correctness of the mechanism, and the one who encounters them always fails [3]”,

Le Bon states in The Psychology of Socialism.

All this gave reason to the French philosopher Pierre-André Taghieff in his book La couleur et le sang: Doctrines racistes à la française, following the left-wing sociologist Pitirim Sorokin, to enroll Gustave Le Bon in the ranks of social Darwinists.

Thus, by emphasizing the hereditary determinism of the collective unconscious, Le Bon finds himself in the political space of conservatism: stability and repetition are primary in the development of peoples. Since evolution and adaptation are necessarily slow, all attempts to speed them up with revolutions or reforms that are too fast are doomed to failure. The most dangerous, according to the French sociologist, are political utopias based on “leveling theories”: anarchism, communism, socialism, feminism [5].

Political forecasts of a French sociologist

The French sociologist, like none of his contemporaries, managed to predict the inevitability of a big war for the redivision of the world and predict the inevitability of establishing a regime based on militarism and social populism in Germany [2].

In The Psychology of Socialism, there is already a growing sense of instability, both globally and in the West. Lebon notes the rapid breakthrough of the countries of the East, whose races are becoming more and more competitive for the peoples of the West. The most dangerous thing for him seems to be China's entry into the path of industrial development. In this case, the gigantic natural resources, large population and low cost of labor will make the Celestial Empire "the regulator of markets, and the Beijing Stock Exchange will set prices for all world goods" [2].

In addition, Le Bon, in the pages of The Psychology of Socialism, tries to comprehend the rapid breakthrough of Kaiser Germany and the consequences of this for the rest of Europe. For Le Bon, both Kaiser's Germany and German socialism are inextricably linked with militarism and general conscription, which not only created a colossal industry, the organization of which the author of the Psychology of Socialism admires (in his opinion, she has already outstripped the English and is able to compete with the American), but and changed the very spirit of the Germanic race.

The French researcher believes that in the near future Germany will start an open struggle to revise the existing status quo. At the same time, the Latin race is approaching a dangerous threshold, after which Spain, Italy and France will cease to be powerful states. Either the Anglo-Saxon states or the German Empire will come to the fore [2].

Analyzing these processes, the French researcher draws a conclusion about the inevitable growth of militaristic tendencies in the coming XNUMXth century. The study of the works of the creator of the "sociology of the masses" gives grounds for broader conclusions: Le Bon tried to reflect in his concept some of the pan-European political processes that caused the crisis of classical nationalism.

The aggravation of the economic struggle and the establishment of an authoritarian nationalist regime in Germany (in the future, seen by Le Bon in the form of militarized socialism) creates, according to the French conservative, a qualitatively new foreign policy situation [2].

Le Bon constantly recorded the gradual transition of European countries from a simple concept of a balance of interests (searching for compromises or local wars) to a strategy of forceful containment, which inevitably intensifies the arms race. The French conservative points out that this policy is increasingly associated with vital economic interests.

On this basis, he makes a reasonably correct prediction that

Conclusion

- writes the historian N. Lepetukhin, believing that this, along with Lebon's anti-parliamentarism and racism, is one of the reasons for the silence of his name in the public field.

Nevertheless, the influence of Gustave Le Bon on the civilized world is really great - all those who made revolutions often read his works on the psychology of the masses.

In addition, the French sociologist's criticism of contemporary democracy led to a revision of the essence of the concept of "national idea". Lebon points out that, in terms of their mental make-up, it is the crowd that is the most staunch guardian of traditional ideas and opposes their change. However, this traditionalism is entirely dependent on outstanding personalities who must ensure the peaceful development of mass society [2].

It could be assumed that in the future, after a long work, the crowd will be able to become a group of conscious citizens capable of making independent decisions. But for LeBon, such a scenario seems unlikely. Much more likely to him is a repetition of Roman history: an uprising of the masses, culminating in the establishment of dictatorship and despotism. Only reliance on tradition and natural conservatism can prevent such an uprising and the establishment of a military-police regime.

Thus, the French traditionalist conservative completed his revision of the Enlightenment ideals: in his concept, a person is not born as a “blank sheet of paper”, but is entirely under the control of his own heredity and innate abilities. Therefore, rejecting the theory of "natural equality" of Voltaire and Diderot, Lebon inevitably questioned the postulates of 1789 on the right of the people to the supreme exercise of political power. In Lebon's sociology, only outstanding personalities have the right to supreme power, and national unity itself is ensured by unconscious heredity, which makes his theory related to the radical nationalist theories of the first half of the 2th century [XNUMX].

References

[1]. Gustave Lebon. Psychology of peoples and masses. - M., 2011.

[2]. Fenenko, A. V. "National idea" of the French conservatives of the XIX century / A. V. Fenenko. - Voronezh: Voronezh State University, 2005.

[3]. Gustave Lebon. Psychology of socialism / G. Lebon per. from fr. – 3rd edition – M.: Sotsium, 2020.

[4]. Lepetukhin, N.V. Theories of racism in the socio-political life of Western Europe in the second half of the 2013th - early XNUMXth centuries: J.-A. Gobineau, G. Lebon, H.-S. Chamberlain / N. V. Lepetukhin; FGBOU VPO "IGASU". - Ivanovo: Presso, XNUMX.

[5]. Tagieff P.-L. Color and blood. French theories of racism. – M.: Ladomir, 2009.

[6]. Picard E. Gustave Lebon et son oeuvre. Paris, 1909.

[7]. Nye, R. The Origins of Crowd Psychology / R. Nye. – London, 1975.

[8]. Spengler O. The Decline of Europe: Essays on the Morphology of World History. T. 2. World-historical perspectives / Per. with him. S. E. BORICH - Minsk: Potpourri, 2009.

[9]. Korniliev VV Negative consequences of the development of mass psychology as part of social psychology. // Psychology and Psychotechnics. – 2013.

Information