"Toad head" from all the vicissitudes of fate

If you saw the movie "City of Masters" (1965) in your distant childhood, then you may remember that such a helmet is shown in it, however, it is worn by an infantryman, not a rider. Apparently, the film's costume designers found it somewhere and decided to use it as a purely knightly attribute!

There spears and helmets burn in the sun,

Bertrand de Born, The Song of the Minstrel, translated by A. A. Blok

History knightly weapons. Recently, we have somehow moved away from our knightly theme, but it is nowhere in history. weapons didn't leave. Moreover, we have not yet considered much in it, and today one of these gaps will be eliminated - we will tell VO readers about the so-called “toad head” helmets (frog-mouth helm in English) or stechhelm (stechhelm in German) - a very original type of helmet, characteristic of the XNUMXth - and the entire XNUMXth century.

"Toad helmet". Miniature from "The Romance of Tristan". 1410-1420 France. National Library of Austria, Vienna

And here is another very curious miniature from The Romance of Tristan. It very clearly shows how a knight in a “toad's head” helmet strikes with his spear under the visor of his opponent's bascinet helmet and hits the chain mail covering his throat. Obviously, this blow for the rider who received it will be fatal!

And here we see that the flat tops of the "toad's head" could also be decorated, and they even wore crowns! Miniature from "The Romance of Tristan". 1410-1420 France. National Library of Austria, Vienna

Moreover, this helmet, no matter what the miniaturists draw in their manuscripts, no one has ever used in real battles. And they used it exclusively as a tournament helmet for a spear tournament duel - geshteha. That is why he had such powerful protection for the neck and entire face. Traditionally, it was included in the tournament semi-armor kit, which was called shtekhtsoyg. This helmet was not mobile, but on the contrary, it was completely motionless attached to the cuirass in order to form a single whole with it.

Miniature of Jean Fouquet from the Book of Hours of Simon de Vary with a portrait of the client. 1455 Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The characteristic features of this helmet are as follows: first of all, the flat shape of its upper part and the wedge-shaped front part extended forward. Thanks to this, no matter where the tournament spear fell into this helmet, it always slipped off it. The back of the dome was rigidly connected (by forge welding or with rivets) to the dome of the helmet. It turned out that the protection of the face, neck and collarbones were combined into one. This achieved complete solidity of the protection of the upper body and the exceptional strength of the helmet itself, arranged so that inside the head of its owner would not touch the metal itself anywhere!

We continue to study the miniatures from the "Romance of Tristan". In this miniature, we see how the knights exchange blows directed at each other's helmets, but they cannot cause any harm!

Nevertheless, this helmet could be removed from the cuirass. To do this, he had a buckle at the back for fastening a cuirass to the back, and a latch at the front, which provided a rigid attachment of the helmet to the breastplate.

But on this miniature from the novel "Lancelot du Lac" (also "The Death of King Arthur"), 1400-1425. Paris, National Library of France, something strange is depicted - a foot duel with swords, and both combatants are depicted in helmets "toad's head", and even with additional holes for breathing. It seems that there are no such helmets in any of the museums ... And for some reason blood is literally gushing from under these helmets. How did you have to try so hard to get hurt like that in these helmets?

A black and white photograph from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, showing a complete tournament armor from the collection of this museum, along with a toad head helmet and besagu round plates to protect the armpits

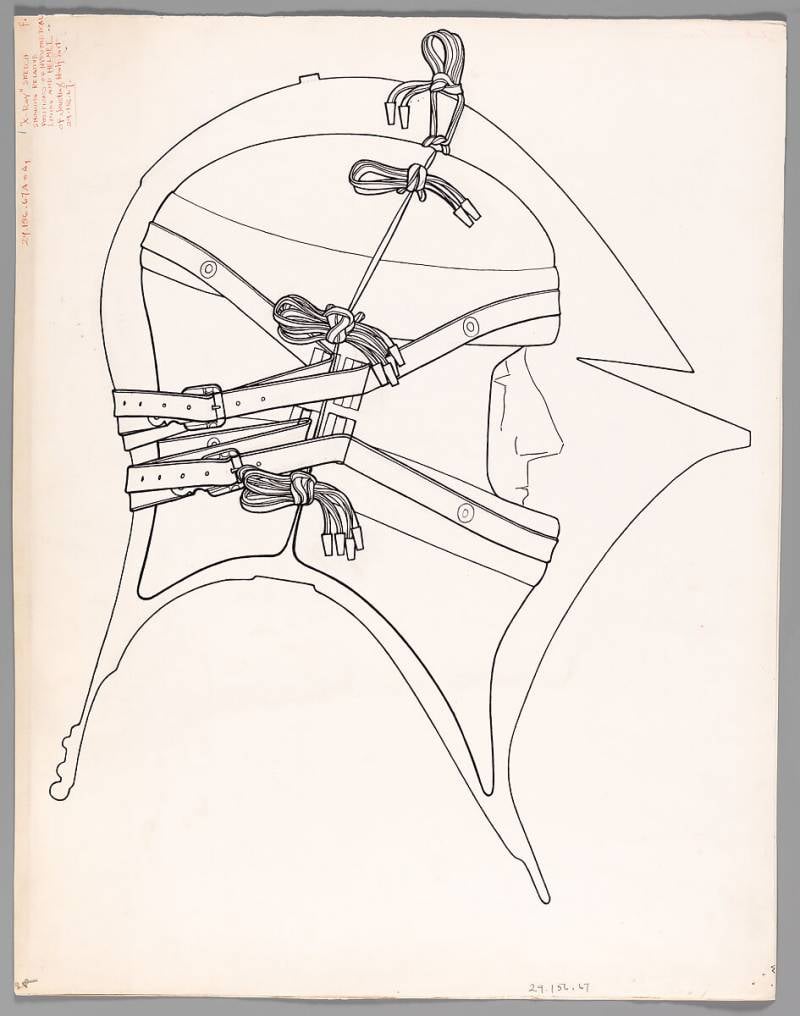

The balaclava had a rather complex design and was designed in such a way that it was tied to the helmet from the inside, but its ties were tied on the outside. And it was thick enough to protect the wearer's head from injury in the event of a direct blow to the helmet with a spear.

Tournament armor with a "toad helmet" from the collection of the Dresden Armory. Author's photo

Balaclavas and "toad helmet" from the collection of the Dresden Armory. Author's photo

A knight, dressed in the same armor, and on a horse to participate in the so-called "tournament of the world", that is, completely safe for both man and his horse! Metropolitan Museum, New York

Due to the fact that the “toad helmet” did not fit too tightly around the head and neck of its owner, unlike other combat helmets, there was enough room for air inside, so it was not too hard to breathe in it, and it was removed from the head through top.

Toad head helmet, ca. 1500. Most likely made in Nuremberg. Weight 8097 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The same helmet. Side view with balaclava straps

One continuous viewing slot was very high, not at eye level, but “on the forehead”, so that again during a spear duel, when the rider leans forward, he had a good view - but as soon as he straightened up at the moment of impact, no spear could might have fallen into that gap. It simply met a solid wall of steel in front of it, along which its tip slid. Thus, getting into the viewing slot was completely excluded, and there were no other holes (except for the holes for the balaclava strings) on it.

Toad head helmet, 1475-1500 Weight 8769 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

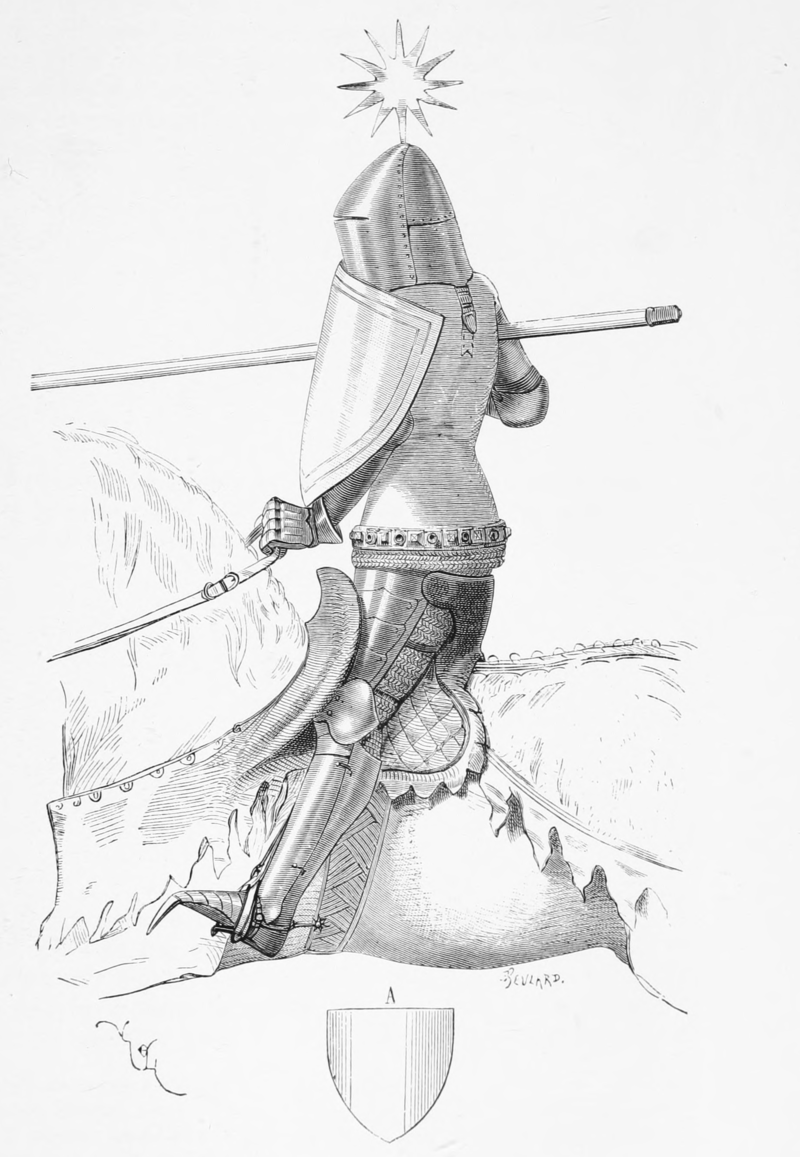

Knight of the middle of the XIV century, dressed in tournament armor. Illustration from Viollet-le-Duc's book. The helmet of the grand helm type is shown very well - a transitional form from the combat topfhelm of the XNUMXth century. to a purely tournament helmet "toad head"

That is, this helmet, in fact, was an absolute protection for a participant in an equestrian tournament. However, this was achieved at a rather expensive price: due to the fact that the thickness of the walls of this helmet was 3 mm or more, its weight could reach up to 10 kg.

And this is how the head of a knight in a balaclava was placed inside the “toad head” helmet. Drawing from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

The origin of the "toad head" helmet can be clearly seen when comparing it with the topfhelm helmet. Rather, with its later variety "sugar loaf", which by the beginning of the XNUMXth century had already fallen into disuse as a combat one, but continued to be used in tournaments. This happened both due to the inertia of thinking, and due to the established tournament tradition that came back from the XNUMXth century.

Miniature from the manuscript "History of the Trojan War", 1441 Germany, German National Library, Berlin

Such helmets with a high crown were convenient to decorate. A voluminous helmet with helmet decorations was clearly visible from afar and made the figure of the rider himself ... more monumental. However, the protective properties of this helmet were also good, and in terms of protection, "sugar loaves" even surpassed bascinets.

Cuirass and armor helmet stehtsoyg, 1494 (with later replacements and additions). Made by Lorenz Helmschmid (Augsburg, c. 1445–1516). It was part of an armor ordered by Maximilian I (Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 to 1519) from two famous gunsmiths, the brothers Lorenz and Jörg Helmschmid. The armor was used in tournaments held in Innsbruck, Austria, in honor of Maximilian's marriage on March 16, 1494 to Bianca Maria Sforza (1472–1510). Quite popular in the German-speaking territories, the gestech was a form of duel in which two opponents on horseback used blunted spears to dislodge each other from the saddle or strike at the tarch (small shield) covering the chest and left shoulder. The armor used for the geshtech included a helmet firmly fixed on the chest and back, as well as two hooks - supports for the spear in front and behind, so that the rider could hold the spear in weight. It is believed that these parts were made in 1494. The total weight is 19,94 kg. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

In addition to the hook in front, this armor also had a hook in the back ...

That is why, even in the XNUMXth century, topfhelm was still used in tournaments, and they were especially popular in England. And, of course, all gunsmiths sought to improve their protective properties, since now the need to have a good view of the helmet for hand-to-hand combat no longer existed. After all, tournaments began to be divided into horse and foot fights, and the armor for them was also special. Now no one in armor for a foot combat entered into an equestrian battle, just as a horseman in armor for equestrian combat did not participate in a foot battle. The unity of combat and tournament armor is now in the distant past!

And again, a very instructive miniature from the "Romance of Tristan" - a knight in a "sugar loaf" helmet strikes with a spear directly into the viewing slot of his opponent's sallet helmet

The helmet began to be assembled from metal plates, gradually stretching it in height and forward, and the viewing slots, taking into account the rider's landing in the tournament saddle, were raised higher and higher. Over time, the "sugar loaf" completely lost its qualities of a helmet for hand-to-hand combat, lost its pointed crown - and that's how it turned into a "toad head". That is, a helmet that has become an extremely popular element of tournament equipment for geshtech, for which in the first half of the XNUMXth century even a special set of tournament armor was created, called shtekhtsoyg.

Another miniature with a knight in a toad head helmet. Manuscript "Tristan and Isolde", 1447-1449. France. Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Moreover, this helmet existed until the very disappearance of tournament fights, it was so comfortable and functional. That is why many of these helmets have survived to this day and are exhibited in various museums in both Europe and America. Stehhelm also gained great popularity as a heraldic helmet, indicating that its owner belonged to the nobility, that is, in the past - to the knightly class.

Information