Mulberry Pier - D-Day Secret Weapon

Researcher stories the landing of allied forces in Normandy Alan Davidge wrote:

Brave men also have to rely on engineers, planners, and the right politicians to do whatever it takes to keep their frontlines moving. All the combat exercises that were so diligently practiced on the eve of June 1944 would be pointless if Churchill, the British War Office and the Admiralty did not work together to provide them with material support through construction artificial portsto be installed on D-Day beaches».

Inanimate objects are spoken of as living things only in exceptional cases.

The story of the construction of artificial berths "Mulberry" (mulberry, mulberry) became just such a case. In the Battle of Normandy, they really do seem like incredible heroes.

For the liberation of Normandy and eventually all of France and Western Europe, the contribution of these man-made harbors, which supplied the troops after D-Day with vital supplies, was highly appreciated by all Allied military forces.

In 1940, the British were lucky to carry out a successful, albeit somewhat chaotic, rescue operation to evacuate troops from Dunkirk. Once the mission was completed, W. Churchill and his generals began planning the day when British and Commonwealth troops would return to French beaches. He hoped that their American compatriots would accompany them. But in 1940 it was more fantasy than reality.

Therefore, the primary task before the invasion of Europe and Churchill's immediate concern was to prevent a German invasion of Britain, to increase production weapons and a guarantee that the country will not die of hunger.

German soldiers on the coast at Dunkirk after the escape of the Allied forces, May 1940

If Britain survived this attack and reached a position where an invasion of Europe was possible, it would be clear that the enemy had already built up defenses along the French coast. In particular, he strengthened existing ports from attacks, where troops could land in large numbers and where large supply ships could unload the valuable cargo they needed to further penetrate enemy-occupied Europe.

In the end, Britain survived.

The United States joined in December 1941. She managed to defeat Rommel in North Africa in the fall of 1942, which allowed Churchill to add a little optimism to himself:

His caution was partly due to the results of the failed raid on Dieppe in August 1942, when the Allies discovered what could happen if they tried to seize one of the ports of the English Channel.

The joint Anglo-Canadian attack went down in history as a very painful wound, as a result of which the losses amounted to 70%. But military planners were able to turn this negative moment into a positive moment. A possible plan to invade Europe, the future Operation Overlord, would not include a portion of the coastline where the Allies would have to seize ports.

Dieppe Raid Result

Mulberry project, preparation and testing

Vice Admiral John Hughes-Hallett, who commanded fleet during the raid on Dieppe, he categorically stated after the operation that if the seizure of the port was impossible, then the port would have to be thrown across the English Channel.

This was met with ridicule at the time.

However, the concept of an artificial port or Mulberry Harbor began to take shape when Hughes-Hallett moved to the position of Chief of Staff of the Navy and was directly involved in the planning of Operation Overlord.

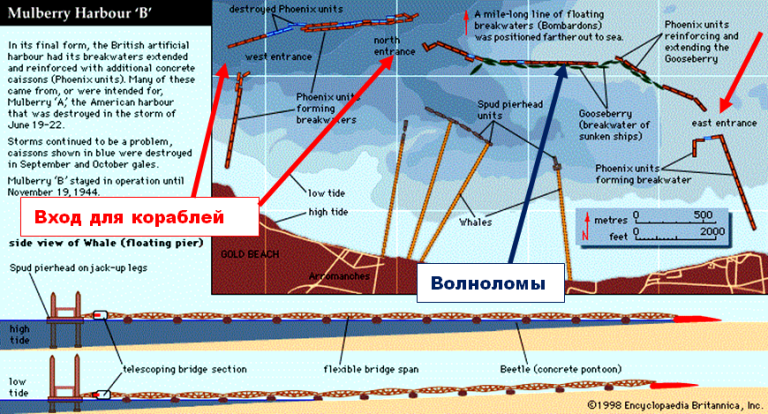

Mulberry was the code name for all the various structures that were to create artificial harbors. These were "gooseberries" - sunken old ships, external floating breakwaters (breakwaters) called "Bombardons", static breakwaters consisting of reinforced concrete caissons called "Phoenix", floating piers, a roadway code-named "Whale", floating floats " Beetle "and the head of the pier codenamed Spuds.

An interesting fact should be noted here.

In 1917, W. Churchill, as Minister of Armaments, developed a detailed plan for the capture of two islands, Borkum and Sylt, which lie off the coast of the Netherlands and Denmark. He proposed the use of flat-bottomed barges or caissons measuring 37x23x12 m, which would form the basis of an artificial harbor when it was lowered to the seabed and filled with sand. However, events went further, and Churchill's proposal was imperceptibly forgotten.

In 1941, some of the ideas for creating artificial harbors were also presented by the leading civil engineers of the Navy, the military and scientists.

Thus, Professor J.D.Bernal expressed similar ideas, developed by Brigadier General Bruce White, who later helped form the plans for the final design of the Mulberry. He was greatly assisted by Allan Beckett, whose "whale" roadway design was chosen instead of Hamilton's Swiss Roll and Hughes' concrete Hippo (more on this below).

For a project of this size and complexity, it's no surprise that there have been several major players in Mulberry's history. But the actual author of the final concept of Mulberry Harbor is still considered Hughes-Hallett.

The authors of the plan to land on the European coast were trying to convince Hitler that the invasion would take place in Calais, but in fact it would take place on the sandy beaches of Normandy.

At the same time, there was only one problem in the plan of the operation: as soon as the landing ships began to land the assault troops on the beaches, where would the supply vessels that require deep-sea and port facilities be able to dock in order to unload the equipment necessary for the invasion and for moving inland?

The answer to this question turned out to be very exotic and incredible. It consisted of a plan for the construction of temporary deep-water harbors with their further relocation to the shores of Normandy. This decision was supported by Prime Minister Winston Churchill himself.

To bring Mulberry's plan to life, the War Department, under the leadership of Brigadier General Bruce White, who turned the engineers' ideas into reality, created a new department, Transport 5.

As you might expect, there were a number of opinions on how best to proceed, and many conflicts between politicians and the military, as well as experts in the field of engineering. Like the early experiments with flying machines, a project of this magnitude has never been implemented before. But unlike manned flights, the development of the mobile harbor proceeded with tight time constraints and a desperate need for secrecy during the war.

Thus, Admiral John Leslie Hall, Jr. expressed the opinion that after the United States joins the operation, its large LST (tank landing ships) will be able to carry out the work of transporting goods and vehicles without the need for artificial harbors. But at the same time, it was noted that their work would depend on the daily tides. In fact, the LSTs performed well in the latter half of D-Day, and some military historians still hypothetically claim that they could provide all the necessary supplies for the advancing troops.

But be that as it may, it was decided to make a pier.

By the summer of 1943, it was decided that the proposed artificial harbors would need to be prefabricated in the UK and then towed across the English Channel.

For their construction, sites were selected on the west coast of Great Britain, in the south of Scotland on the coast of the Solway Firth and in North Wales in Morph. Here the coastline was sufficiently similar to that of Normandy to allow for the initial engineering experiments.

Also by mid-summer 1943, a subcommittee on artificial harbors was organized, chaired by civil engineer Colin R. White. The first meeting of the subcommittee was held at the Institute of Civil Engineers (ICE) on August 4, 1943.

Initially, special attention was paid to floating passages and the foundations of piers, excluding breakwaters (breakwaters). Then we moved on to discussing breakwaters. Initially, it was assumed that compressed air structures would be used, then block ships were proposed and finally, due to the insufficient number of block ships available, a mixture of block ships and specially made concrete caisson blocks.

Concrete, or rather reinforced concrete, was chosen for the construction of caissons for several reasons:

1) in comparison with the use of metal, it simplified and reduced the cost of production by at least a third;

2) made it possible to use the labor of low-skilled workers;

3) concrete is not subject to corrosion, easy to work with, so the speed when working with it is higher than when working with metal;

4) concrete is easier to transfer loads (but not sharp impacts) and is more maintainable.

With a limited time frame, all this was of great importance.

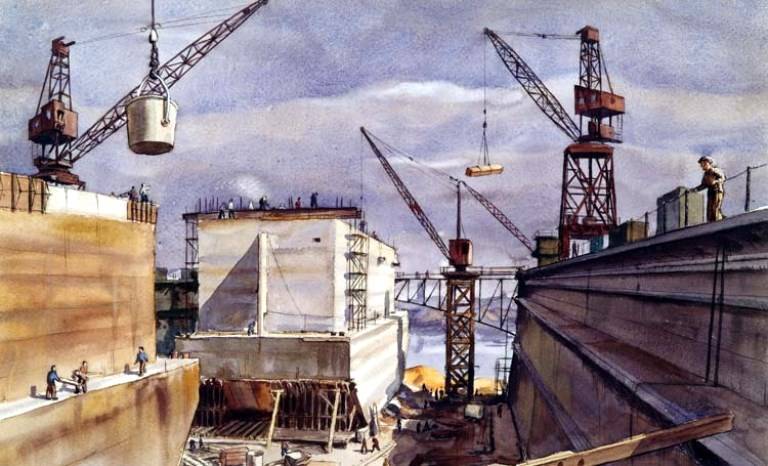

A painting by Dwight Schepler shows the construction of the Phoenix concrete coffered blocks that were being built in Portsmouth, England. They were then towed across the English Channel at 3-4 knots, where they were flooded to create breakwaters.

However, the work proceeded slowly.

This threatened that W. Churchill could become disillusioned with this project. Back in May 1943, he wrote the following note to Colin R. White:

In August 1943, the Quebec Conference agreed on the need for the construction of two separate artificial harbors - one American and one British-Canadian.

Some of the construction workforce came from the military, but since many of the eligible young men with the necessary practical skills had already served in the army, new construction workers had to be found and trained. And to do it twice as fast as usual.

For this purpose, construction camps were set up, where men and women, among whom were many refugees from war-torn Europe, worked in secret to bring the tests of the prototypes of the project as quickly as possible.

At the beginning of September 1943, three versions of berth designs were submitted for testing. Simultaneously with them, the breakwater (breakwater) was tested using compressed air.

The first option was presented by Hugh Yoris Hughes, a civil engineer who designed the steel spans of the Crocodile Bridge and the concrete pillars (caissons) of the Behemoth that supported the bridges.

The second project was developed by Ronald Hamilton (worked in the Department of the development of various weapons). His invention - the "Swiss roll" - consisted of a waterproof canvas, which played the role of a road, and the roadway itself was reinforced with slats and stretched cables.

The third project was submitted by Lt. Col. William Teiball and Major Allan Beckett (of the Department of Transportation 5 (Tn5) of the War Department), who designed a steel floating bridge on pontoons connected to the head of the pier. The latter had built-in adjustable supports that rose and fell with the tide.

Prototypes were built at the Morph plant in Conwy, North Wales, employing more than 1 local and external workers for this purpose. One of them was Oleg Kerensky, the son of the former Russian prime minister, who oversaw the construction process.

Prototypes for each project were tested at Rigg Bay on Solway Firth.

The testing allowed the engineers to evaluate the characteristics of the subassemblies and the entire assembly as a whole. It was found that the floats did not rise or fall with the tide as predicted, but Hughes found a solution in making the span between the behemoths and the carriageway adjustable.

A more serious problem was the unexpected roll and yaw of the caissons, which caused the attached roads to buckle. Hughes proposed to build smaller "hippos" on which the road would be located.

It wasn't just Hughes' design that faced problems. When the “Swiss roll” carriageway from Hamilton was tested with a 3 ton dump truck, the carriageway sagged in less than two hours. Adjustments were made, but further testing on the high seas confirmed that its 7 tonne carrying capacity is well below what is required for transport. tank... The construction of the roadway of this bridge was soon abandoned.

The best results were obtained with flexible Beckett lintels supported by pontoons.

However, the final choice of design was determined by a storm, during which the hippopotamus supports were torn from their places, as a result of which the spans of the Crocodile Bridge collapsed and the Swiss roll was washed away.

The Tn5 design proved to be the most successful, and the Beckett pontoon bridge (later codenamed "Kit") remained intact. As a result, this project was accepted for production. A little later, under the leadership of D. Bernal and Brigadier Bruce White, Chief of Ports and Inland Waterways at the War Department, a 16 km road, code-named Whale, was built from the Keith Bridge for testing.

Beckett bridge tests

Whale Road from Beckett's Whale Bridge in readiness

At the same time, the British Royal Navy was closely studying the French coast. In both locations, temporary harbors required detailed information regarding geology, hydrography and sea state.

Initially, planners began collecting old photographs and matching them with reconnaissance photographs to get an idea of the topography and defenses of the beach. They also began to observe the tides in Normandy, which rose and fell 6,4 m twice a day.

Major Carline, Quartermaster General, Sir Riddle Webster, Brigadier General Bruce White and Major Stear Webster examine the plans at Garliston Harbor.

To collect more accurate data in October 1943, a special group of hydrographs was created: the 712th Reconnaissance Flotilla, operating from the Tormentor naval base. The task of the flotilla was to collect depth measurements off the coast of the enemy, for which a small landing ship was used from November 1943 to January 1944.

The group made its first exit to the shores of Normandy on the night of November 26-27, 1943.

Then, in secret raids late at night, samples of sand, mud and rocks were collected to help understand the geology. In addition to confirming that the water would be deep enough for the harbor, this data provided information that heavy vehicles would not get stuck in the sand after leaving the pontoons.

As a result of these efforts, scale models of the proposed landing beaches were built, which facilitated the rapid progress of work.

And only after thorough reconnaissance, long months spent at the drawing board, and experiments, which were carried out in complete secrecy, were the final decisions taken.

It should be said that the project itself entered the construction phase much earlier, at the beginning of autumn. The welcome to start work was given on September 4, 1943.

The two massive artificial harbors involved 300 companies, employing 40 to 45 workers, many of whom did not even have construction skills. The task of this workers' army was to build 212 caissons with a carrying capacity of 1 to 672 tons, 6 piers and 044 miles of floating roadway.

Locations throughout Britain have been selected for the production of the components of the project. These pieces would eventually have to come together into one dynamic puzzle or Lego monster. For example, huge concrete caissons were built in new dry docks at the mouths of the Clyde River in Scotland and on the Thames downstream of war-torn London. Metal floats were built in Kent in the southeast of England and along the south coast in areas around Southampton.

Phoenix caissons under construction, Southampton, 1944

As stated above, it was decided to create two artificial harbors: Mulberry A will be located on Omaha Beach to supply the western part of the invasion zone, and Mulberry B will be installed on Gold Beach in Arromanches-les-Bains to supply the eastern part of the D-Day beaches ...

The entire construction project was completed in just six months, an astonishing achievement, and although it was carried out under the strictest secrecy, there were one or two threats to its safety.

The final stage of testing. The British Crusader tank heads from Cairne Head to Garliston Harbor, Scotland, on the Allan Beckett floating road. This location was chosen because the tide level here reaches 7,3 m, like in Normandy. The photo clearly shows the pontoons "beetles" on which the road elements "whales" rest

The worst happened when the British traitor and renegade announcer William Joyce (alias Lord How-Howe) announced that the enemy knew all about the concrete structures that were being built to be flooded off the coast to create harbors. He then sarcastically said that the Germans would save the British forces from the effort and sink them themselves.

This caused alarm, but not panic, and the British codebreakers at Bletchley Park got to work, intercepting any messages that might indicate what the Germans knew. In the end, one message was discovered indicating that the enemy considered it to be just anti-aircraft towers.

Additional precautions were taken in the aftermath of the William Joyce incident. Along with the planning of Operation Overlord, a deception plan — Operation Fortitude — was developed to convince Hitler that when an imminent invasion occurred, it would be in the Dover Calais area, the shortest distance between England and France. To reinforce this misinformation, one concrete caisson was towed to the English coast near Dover.

Artificial pier construction

Now we will look at what the artificial berths consisted of.

The basic structure was a ring of breakwaters (breakwaters) with three entrances for cargo ships. Once in this protected environment, ships will be unloaded onto the piers and supplies will be transported ashore by trucks traveling on floating roads.

The structure consisted of three main components: breakwaters, piers and a carriageway.

Scheme of the main parts of Mulberry berths

The breakwaters consisted of three components. The first of these were the cruciform bombardons, which were floating breakwaters fixed in place and forming the first point of resistance to the waves and tides of the English Channel.

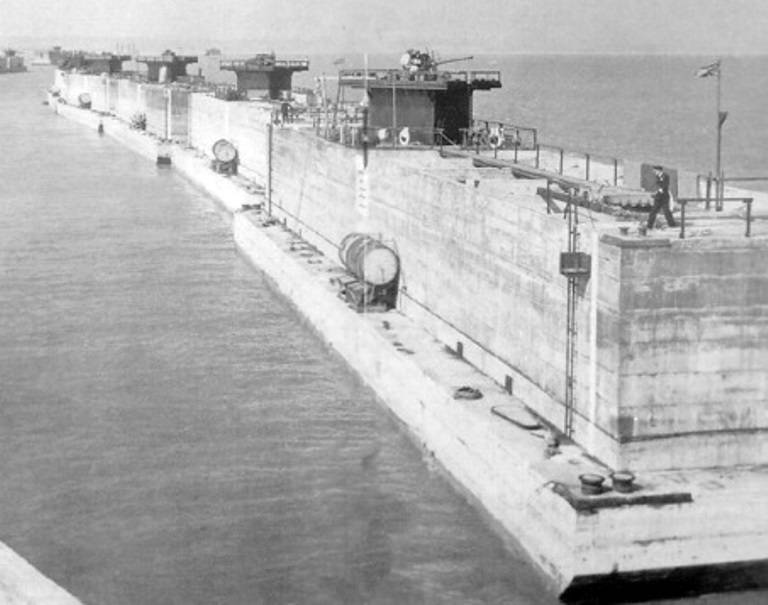

The second part was huge concrete caissons, code-named "Phoenix". They were hollow inside, and special valves were located in the lower part. As soon as the valves opened, water entered the middle of the caisson and pulled it to the bottom. By adjusting the valves, "phoenixes" could be installed at a certain depth. There were 146 such "phoenixes" in total. They were 59,7 m long, 18 m high and 15 m wide.

Mulberry A Concrete Caissons

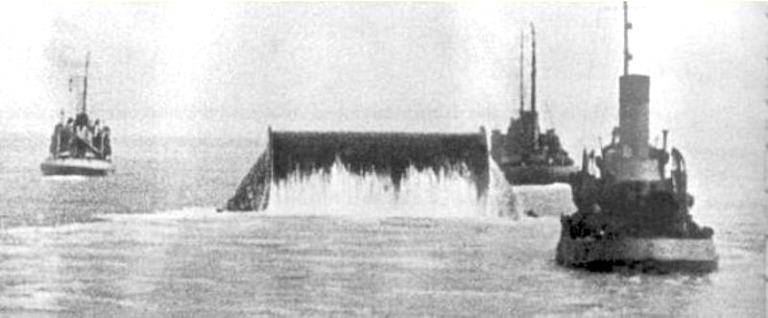

The Phoenix caissons were moved into place by tugboats, forming a continuous line of breakwaters (breakwaters)

The last piece of the breakwater puzzle was an armada of old ships known as "block ships" that crossed the English Channel. Many of them went on their own and in the final act of service were flooded in relatively shallow water to complete the ring of breakwaters. The sunken ships were codenamed "Gooseberry". A total of 70 ships were sunk. Inside this ring there were three passages (north, east and west) for supply ships through which they entered the inner water area.

Several dozen ships were also scuttled as breakwaters and at other landing sites to help unload the LST.

Once inside the breakwaters, ships and barges anchored at the head of the pier for unloading. This part was codenamed Spuds and was held on the seabed by four sturdy pillars. The pylons were built with platforms that could be raised and lowered by electric motors depending on the tide. The platforms, in turn, were connected to the shore by Allan Beckett's floating roads.

The photo clearly shows the piers and the pier, as well as the "Kit" floating bridge connected to the pier

The roads were the phase of the construction project that took the most time to perfect.

Sections of the roadway, 24,3 m long, codenamed “whales”, were attached to floating pontoons called “bugs”. These concrete and steel structures had to withstand 56 tons of the weight of the "whale" plus another 25 tons of the tank that would move along them. The roads were connected to the beach by a buffer or driveway.

Black American soldiers build a driveway at the end of a floating road as part of Mulberry A on Omaha Beach. The span was a steel mesh laid on top of wooden poles.

There were also built pontoons with a mechanical drive called "Rhino" for the delivery of goods to the shore.

Mulberry Pier on D-Day

A large number of British and American tugs were requisitioned to tow the Mulberry from the assembly point near Ly-on-Solent to France. They brought parts of the artificial pier out to sea on June 4, 1944, but were stopped in the middle of the canal when D-Day was delayed for a day due to worsening weather. By the time of the first landing, most of the caissons were located about 5 miles from the French coast.

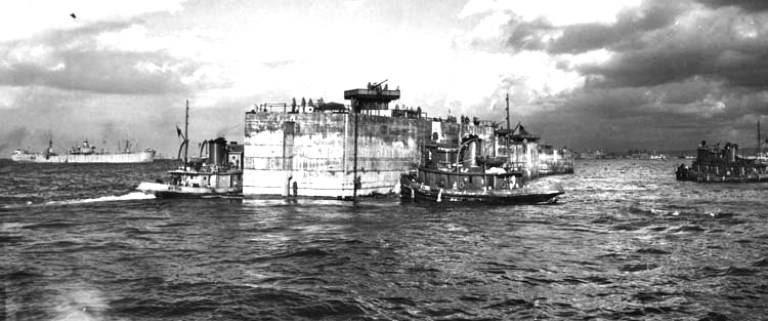

The concrete caisson is being transported by tugs to be installed as a breakwater at Mulbury B harbor. Anti-aircraft guns were installed on the largest caissons, and barrage balloons hovered above them to protect aviation

Mulberry B

The responsibility for Mulberry B, located near Arromanches, lay with the Port Construction and Renovation Group No. 1.

They sailed on the evening of June 6, 1944, and by dawn on June 7, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Mais, special markers were placed at the high tide mark on the landing beach and on the hill behind it. These markers will be used to align the first two supports and their correct position. Further in the sea, marker buoys for caissons and "block ships" were placed in predetermined places.

The journey of the tugs, which pulled the caissons and piers, was difficult and slow. Top speed was limited to three to four miles per hour. The first Phoenix was sunk here at dawn on June 9, 1944. By June 15, another 115 Phoenixes had been sunk to create a five-mile arc between Tracy-sur-Mer in the west and Asnelle in the east.

The caissons had a crew of two who controlled the process of submerging the structure under water. For this, as described above, special valves located at the bottom of the caisson were opened. After being installed in place, the tops of the "phoenixes" were at an altitude of 3 to 9 m above sea level, depending on the tide.

Aerial view of a breakwater from sunken ships, which was installed a few hours after the Normandy landing at Arromanches. Vessels can be seen moving through the passage in the Gooseberry line.

To protect the new anchorage, the superstructure of the sunken ships (which remained above sea level), concrete caissons were equipped with positions for anti-aircraft guns and barrage balloons.

The finding of the anti-aircraft gunners on the caissons paid off when the Mulberry B was attacked by 12 Messerschmitts in mid-July. After a long duel, only three enemy aircraft returned home.

Mulberry B Harbor completed and fully operational. On the right is a breakwater of caissons and "block-ships"; in the center is a row of Spuds pier heads forming a dock with floating carriageways leading to the shore. Together they formed a port the size of Dover.

Mulberry A

Similar operations were conducted on Mulberry A off the coast of Vierville-Saint-Laurent.

The bombardons were the first to arrive on D-Day. Unfortunately, an error in calculating the depth of the water resulted in them being deeper than planned and forming a single rather than double barrier, providing less protection from waves.

The first Phoenix was sunk here on June 9, and the Gooseberry by June 11. It should be noted that here the ships approached the shore under heavy enemy fire. Because of this, the tugs, which accompanied the sinking vessels and were supposed to help in their final positioning, parted earlier than planned. But, by a lucky coincidence, the 2nd and 3rd "block ships" were sunk by the German pilots in approximately the correct positions, which made it easier to complete the task.

By June 18, two berths and four Spuds tops were already operational. Although this harbor was abandoned at the end of June (see below), the beach was still used for disembarking vehicles and supplies using amphibious assault ships (LST). By exploiting this method, the Americans were able to unload an even greater tonnage of supplies than at Arromanches.

Whale Floating Road to Spud Pier in Mulberry A off Omaha Beach

Unloading of equipment from the US 2nd Infantry Division at Mulberry A harbor, in the Omaha landing area. June 16, 1944

Mulberry A has been in use for less than 10 days due to weather conditions.

On the night of June 19, the Normandy coast was hit by the worst storm in 40 years. It came from the northeast — the worst possible direction — and continued to hit the shore for three days. The storm only damaged the Mulberry B in Gold Beach, but the harbor in Omaha Beach was irretrievably destroyed. The ships flew into concrete caissons, which subsequently fell apart. Out of 31, 21 caissons were completely damaged beyond repair.

After a fierce storm on June 19, small ships, vehicles and components of the harbors themselves lie in ruins on Omaha Beach, rendering it completely useless. After that, all supplies were to be brought ashore at Mulberry B until the coastal ports opened.

Breakwaters at both sites, however, were able to provide shelter for many vessels that would have otherwise been destroyed, and some supplies did pass. For example, on the worst day of the hurricane in Arromanches, 800 tons of gasoline and ammunition were unloaded, as well as hundreds of fresh, albeit seasick, troops.

The date June 19 has an even deeper meaning as it was an alternative to D-Day. When the issue of postponing the landing date was being decided on June 5, the meteorologists, having consulted the tide tables and weather forecasts, advised to choose the next date for the operation between June 18-20, when the tides would be favorable. However, Eisenhower still decided not to postpone the operation. And, as we can see, he was right. The consequences of the postponement would be even more devastating to the landing campaign in Europe than the destruction of Mulberry A.

When the storm subsided, the American landing in Omaha reverted to the methods used on June 6. DUKW landing ships, boats and amphibians came ashore at one tide and sailed back with another. In fact, it worked better than expected: the success was so great that at times they surpassed the impressive performance of the Mulberry B.

As a result, it was decided to use some parts of the harbor suitable for restoration to strengthen Mulberry B, which soon became known as Port Winston and began to play its role in the victory in the war. Initially, the pier was used to unload warehouses, but after the Patton breakout at Avranches and the British Bluecoat operation, which drove huge wedges into Hitler's defenses, the port became the main channel for troops to enter Europe.

In late summer and autumn, when Paris was liberated and Patton directed his tanks further towards Germany, the area around Gold Beach and the town of Arromanches became a rabid hive to support the eastward advance.

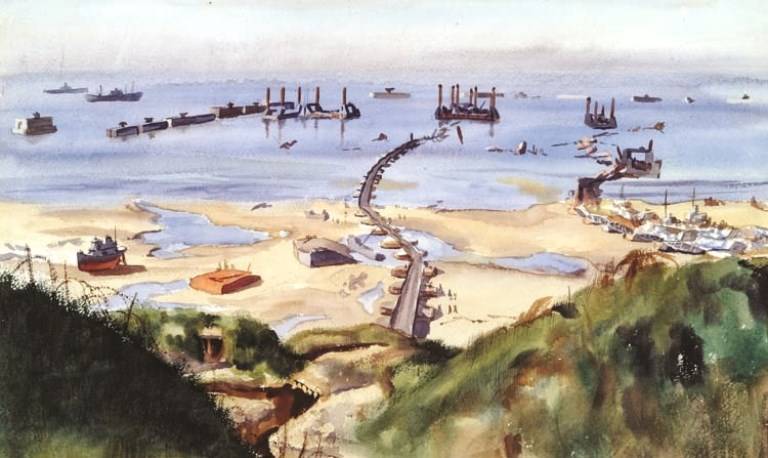

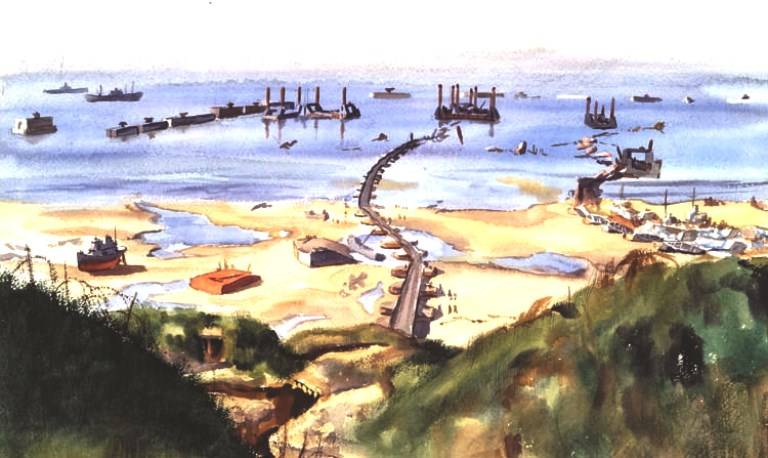

Shepler's painting shows the wreckage of Mulberry A on Omaha Beach after a storm. A row of concrete caissons collapsed on the third day of the storm, allowing the sea to crush piers and floating roads

By November, with the capture of Walcheren, the Belgian port of Antwerp was accessible, and the Allies could organize a new supply line closer to the battlefield. Then Mulberry B was able to breathe a sigh of relief and enjoy his place in history.

It is also necessary to note another miracle of logistics engineering, which is often forgotten - this is the contribution of the "pipeline under the ocean" PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean).

Without sufficient fuel, the Allied mechanized armies would stop shortly after reaching Normandy. So, as with the Mulberry project, engineers were secretly working on an ingenious way to ensure the flow of fuel from the UK to France.

Two separate plans were developed.

The first was a large three-inch flexible hose that looked more like an undersea communications cable than an oil pipeline. The pipeline, transported aboard ships in huge coils, was laid from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg (70 miles - 129,6 km) on August 14, 1944.

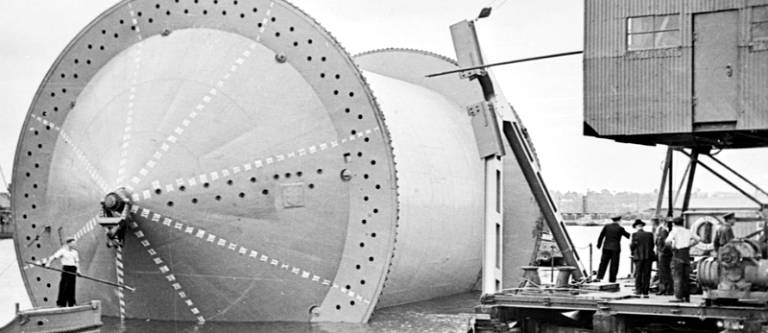

Subsea pipeline reel

The second PLUTO rested on 20-foot (6m) lengths of XNUMX-inch steel pipe, which, like flexible hose, were wound on huge floating reels, codenamed Condundrums.

These deployment systems weighed 1 tons each and were hauled by three tugboats from the UK terminal at Dungeness to the French port of Boulogne, 600 miles (31 km) away. When the coils were unwound, the pipe sank to the bottom of the English Channel.

With these two PLUTO systems, 3,79 million liters of fuel per day could be delivered to the continent.

Laying a pipeline along the bottom of the English Channel

So the value of the harbors' contribution to victory is undeniable, and D-Day planning itself was a huge logistical exercise.

In addition to training first wave assault troops and arming ships and aircraft whose shells and bombs would support the landing, planners had to find ways to organize and store the thousands of trucks, jeeps, tanks, tents, medics and other support personnel that would follow through the piers and bridges to the shore.

The roads and villages of southern England were full of people and cars. One prankster said that the sheer number of barrage balloons floating over British ports and shipyards is the only thing keeping England from sinking. In early June it was estimated that there were three million soldiers in the south of England ready to invade Europe.

Statistics show that in five months of operation, Mulberry B provided access to Europe for two million troops and 500 vehicles. In addition, four million tons of cargo were unloaded to support the release.

From an engineering standpoint, it was equally impressive: the harbor was eventually constructed with 600 tonnes of concrete, 000 tonnes of steel, 31 berths and 000 miles of floating road.

In addition, the project created by-products that could be used elsewhere. For example, many researchers believe that this indirectly contributed to the development of the LST transport ships, which were then in their infancy.

Therefore, the Mulberry project is one of those almost miraculous events like the Dambreaker Raid or Operation Bagration, which, in spite of everything, managed to end the most expensive war in history.

A modern photo showing the remains of the Mulberry B in Arromanches

Bridge over the Moselle river. It consists of sections of the Keith carriageway of one of the Mulberry harbors. The sections have come a long way to Lorraine and 60 years later the bridge is still in use

Information