Combat aircraft. Best friend of a British heavy cruiser

When describing the existence of cruisers in general and especially heavy cruisers, each time a moment arose about the ship aviation... At the beginning of the war, all the heavy cruisers of the participating countries (who had them) carried seaplanes or flying boats. And many light cruisers also had their assistants.

In fact, the "eyes" in the sky were very useful at the beginning of the war, while His Majesty's radar was crawling out of diapers. Then, of course, more compact and looking further, day and night, the radar supplanted the planes. And yet, this is such a page in stories weapons, which is difficult to cross out. But we won't.

Our today's hero is not handsome. And did not deserve such fame as other creations of the designer Reginald Mitchell.

Yes, the one who developed Spitfire. But between the Spitfire and the racing seaplanes, the Walras, developed at the beginning of the 30s, or, if in Russian, the Walrus, modestly huddled.

In general, Mitchell was not particularly fond of seaplanes. More precisely, before joining Supermarine, he paid no attention to seaplanes at all. He worked very far from aviation. But, having come to Supermarine in 1917, already in 1918 Mitchell created a rather successful flying boat Baby. In 1922, a more powerful engine was installed on the Baby, renamed the loud Sea Lion / Sea Lion, and the boat unexpectedly won the Schneider Cup. Well, it floated and flew ...

Mitchell created several successful projects, but the crisis of the 20s sharply reduced the number of orders. And Supermarine was lucky when the Australian Air Force ordered a flying boat.

It was the Seagall / Seagull project - a small flying biplane boat with a wooden fuselage and a pulling propeller engine. The Australians ordered six copies of the machine in 1925, which were used in the interests of geological exploration and topography.

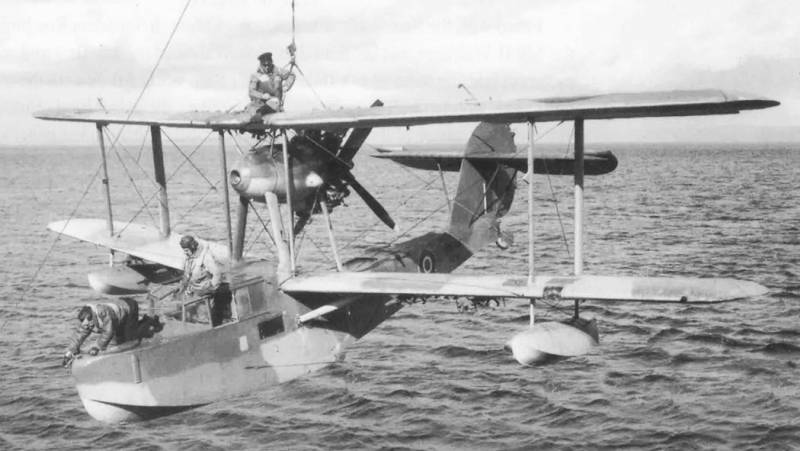

As you know, appetite comes with eating and the Australians wanted to equip their warships with such boats. This did not work with the Chaika, the plane did not have sufficient strength to launch from a catapult. I had to radically alter the plane. The glider was strengthened, it so happened that the propeller turned from a pulling one to a pushing one.

The first flight took place on June 21, 1933. By that time, the Supermarine was absorbed by the Vickers concern. The car was piloted by Vickers' chief pilot, Sumners. The tester liked the car, the only weak point was the not very good handling when steering on the ground, caused by flaws in the design of the wheeled chassis.

Then the car went through a whole cycle of tests.

In 1934, the Australians appeared, who, in fact, ordered the plane. It was interesting for them to observe the start of the plane from the catapult. The launches were demonstrated and the tests continued, both on water and in the air.

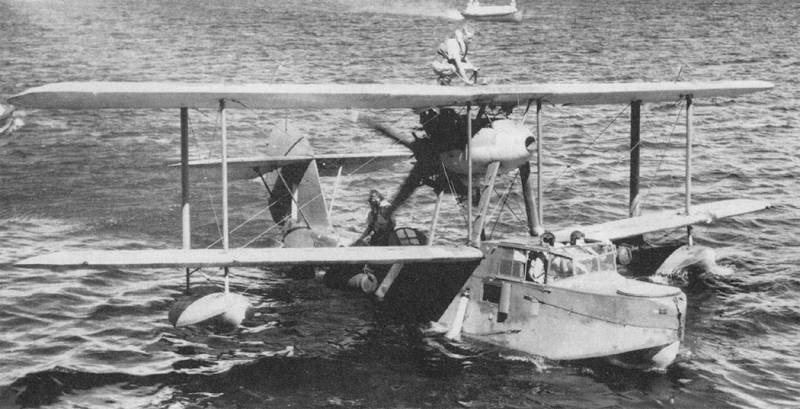

The test results were positive. The seaworthy characteristics were very impressive, the aircraft could take off and land in significant waves, maneuver perfectly, easily took off and landed.

Only minimal modifications were required to make the hull aerodynamically clean, and the engine nacelle was turned to the left by 3 degrees to compensate for the propeller's reactive moment.

As a result, the Australians ordered 24 aircraft. And then an interesting event happened: the British Admiralty suddenly decided that the Royal fleet no modern ejection scout! And an urgent study of the possibility of using the "Sigall" on the ships of the British Navy began.

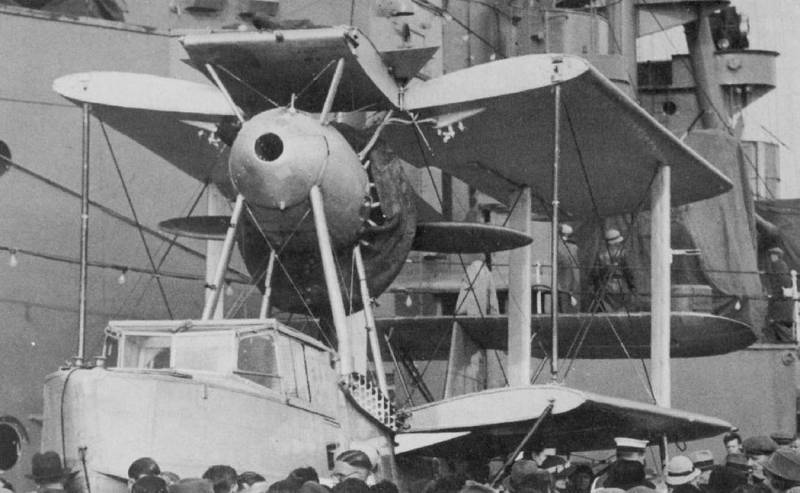

For this, the prototype "Sigall" was used, which remained at the "Vickers". The aircraft was loaded onto the aircraft carrier Koreyges and sent to Gibraltar for additional tests. The aircraft has been flown by many pilots and earned the highest marks.

It was necessary, however, to slightly change the design of the floats and alter the observer's place. And after all these works, the aircraft was accepted on the balance sheet by the Ministry of Aviation.

The flying boat was accepted into the naval service in a single copy. Placing the plane on board the battleship "Nelson", which went to the West Indies. One more flaw was revealed there. There was no chassis status indicator in the cockpit, and the chassis itself, located in the hull of the boat, was impossible to control from the cockpit. And in one of the flights, the landing gear was released when landing on the water. The plane caught on the water with its wheels and turned over.

Nothing, but the commander of the British squadron, Admiral Roger Backhouse, was on board. But everything ended well, the admiral and the pilot got off with a swim. The car was not damaged and, after minor repairs, continued flying.

But you can't fly away from fate, and after a while, while taking off from the surface of the bay of Gibraltar, the plane crashed into an anti-submarine barrier and completely crashed. The crew, however, were not injured.

The Admiralty took these moments into account and nevertheless ordered a batch of 12 aircraft, separately stipulating the installation of a landing gear retraction indicator in the cockpit.

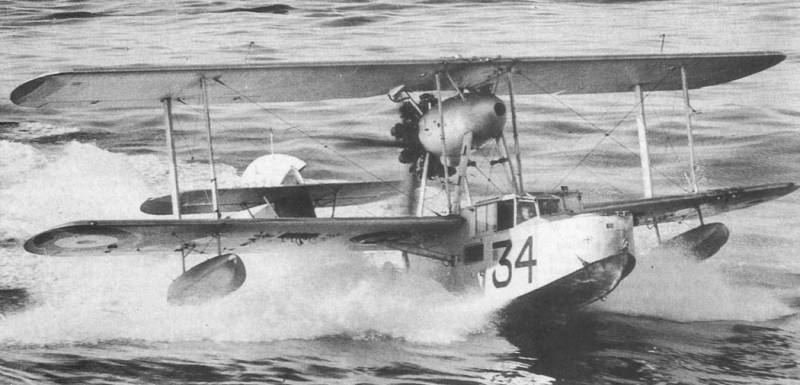

And here a legal rebirth took place: the bird became a sea animal, the Seagull Sigall Mk V turned into the Walrus Mk I.

At the same time, the Admiralty issued Mitchell, as a designer, additional requirements for the aircraft. It was necessary to reduce the wingspan so that they fit into the size of the ship's hangars, or make them foldable, install an autopilot necessary for long flights, and increase the area of the cockpit glazing. Allowed to sacrifice speed characteristics for the sake of structural strength.

The first production Walrus took off for the first time at Woolston on March 18, 1936. Outwardly, the "Walrus" differed from the "Seagull" by the presence of an additional pair of inter-wing struts next to the nacelle and folding back wings. The Walras was the first British Royal Navy aircraft to have a fully enclosed cockpit for a crew of four.

The British command hoped to use the new aircraft quite widely. In addition to reconnaissance, the "Morzh" was supposed to be able to search for and destroy enemy submarines, attack small surface ships and perform search and rescue functions.

The Walrus had something to attack boats and ships. The aircraft's standard offensive armament consisted of two pairs of bomb racks under the lower wing. The inner pair could carry bombs up to 113 kg (250 lb), the outer ones up to 45 kg (100 lb). Defensive armament consisted of two 7,7-mm "Lewis Mk III" or "Vickers K" machine guns in open firing points in the nose of the aircraft and in the middle of the fuselage.

In 1935, "Walras" began to enter service with ships of the Royal Navy. By the time the Second World War began, these aircraft were equipped with more than 30 ships in different fleets and squadrons.

With the outbreak of war, the "Walruses" began to actively patrol the coastal zone of the metropolis as anti-submarine aircraft.

The most significant event for the Walrus was the search and detection of the German raider Admiral Graf Spee. It was the pilots of the "Walrus" who found the raider, but also suffered the first losses. One boat from the cruiser "Suffolk" was missing, and two on the cruiser "Exeter" were seriously damaged by the fire of a German ship.

In 1940, the Walras from the aircraft carrier Glories and the cruisers Suffolk, Glasgow, Effingham and Southampton successfully operated in Norway as night light bombers. During the raids on the positions of the Germans, only one plane was lost. The rest returned safely on the aircraft carrier Ark Royal.

In the process of combat use, "Walruses" have shown their reliability and functionality. In fact, these were aircraft of very high potential.

Two Walruses from the cruiser Suffolk took off to bomb an airfield in Stavanger. Considering that the Suffolk was constantly under attack by the Germans from the air and it was doubtful that the Germans would calmly allow the aircraft to be lifted from the water, it was decided to remove the landing gear from the aircraft and take on board the maximum amount of fuel.

"Walruses" successfully bombed the airfield and, according to the order, set off ... to Scotland! And, by the way, we flew quite successfully. With empty tanks, after five hours in the air, the planes landed in the harbor of Aberdeen.

Then there was the disgrace of Dunkirk, in which all the available "Walruses" rescued the crews and passengers of the evacuator ships, which were sunk by German bombers. Preparation and practice did their job and the crews of the "Walrus" saved many lives.

And then there was an attempt to blockade Great Britain by German submarines that sank ships going to British ports. The anti-submarine specialization "Walrus" came in handy here. Of course, the British Sunderlands and American Catalins were much better suited for this role, but while the Catalins were brought from the United States, while a sufficient number of Sunderlands were built, the little Walras did everything in their power to fight German submarines.

Since the "Walrus" did not have a large range, temporary seaplane bases with fuel and spare parts were set up on small islands around Great Britain, from which flying boats operated.

To improve the effectiveness of the fight against submarines and German torpedo boats, an attempt was made to arm the Walrus with the 20-mm Hispano-Suiza cannon. For this, it was necessary to remove the front turret with a machine gun and the right pilot's seat. The pilot controlled the plane and fired from the cannon from the left seat. The experiment failed and did not go into production.

When Italy entered the war, the Mediterranean became the new arena for the Walrus. Here the boats carried out all possible protection of the convoys and reconnaissance, taking off from the catapults of cruisers and from hydrotransports and escort ships.

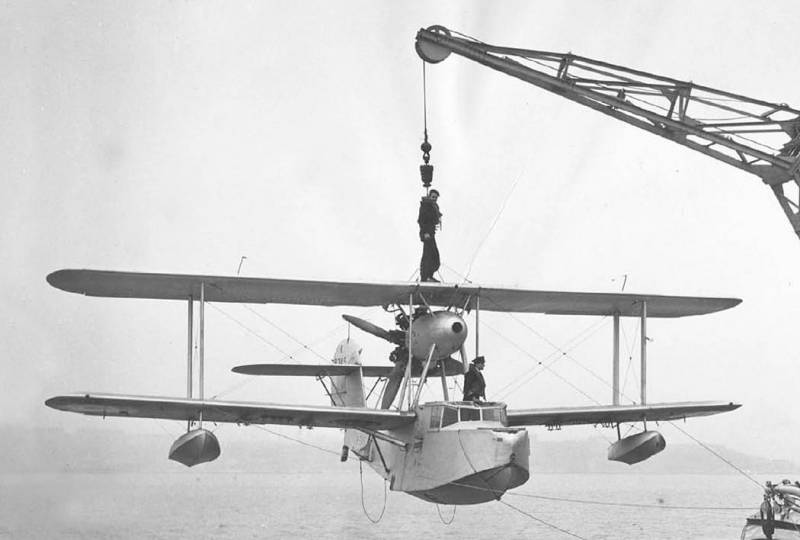

Here the problems that arose in Norway were repeated: in order to take on board a flying boat, the carrier ship had to stall, becoming an excellent target for enemy aircraft and ships.

Over time, it became clear that the best location for seaplanes was the deck of an aircraft carrier or coastal bases. The ship maneuvering under enemy attacks had no time for flying boats. However, in Africa there was enough room for the arrangement of seaplane bases. Although from the catapults "Walras" continued to be used.

The actions of the "Walruses" brought real damage to the enemy. The Walruses of the heavy cruiser London discovered the supply transport of the German submarines Esso Hamburg and the tanker Egerland, which were self-submerged when they were intercepted by the cruiser. A scout from the cruiser Sheffield discovered the tanker Friedrich Brehme, which was serving the Bismarck. The tanker was sunk by the Sheffield. The Walras from the cruiser Kenya found the tanker Kota Penang, refueling the submarine. The boat escaped and the tanker was sunk by the cruiser. The crew of the aircraft operating from the land base in Beirut sank the Italian submarine Ondina.

But 1942 was the final year in the Walrus's combat career. The principles of using ships were changing, radars were massively used. On some ships, flying boats served until the very end of the war, but on the majority of ships in the British fleet, the catapults were dismantled by the end of 1943. And in July 1943, the serial production of the Walras was completed.

However, the aircraft's career was not over. On the contrary, a new round has begun.

In the spring of 1943, massive Allied air raids on German cities began. During the day the city was bombed by the American "Flying Fortresses" and "Liberators", at night the "Lancaster" and "Halifax" were working. These vehicles had large crews (8-12 people) and in the event of a forced landing on water, which was enough on the route, the rescue of such crews became a problem.

And here the "Walrus" came in very handy, given its ability to take off and land on the water even with significant waves.

More than a thousand members of bomber crews were rescued by the Walruses from the waters of the seas surrounding Britain.

In general, the "Walruses" rescued pilots not only on the seas. There was a case in New Guinea when the American pilot Carter, shot down in battle, parachuted over the territory occupied by the Japanese. However, Carter was very lucky: the Fly River flowed nearby. And while Japanese soldiers pushed their way through the jungle to grab the pilot, Australian rescuers boarded the river and took Carter away.

After the end of the war, "Walruses" were used for a long time for peaceful or almost peaceful purposes. Several vehicles continued to work as scouts in the whaling fleets of Britain. It got to the point that a catapult, dismantled from the cruiser Pegasus, was even installed at the Balaena whaling base.

A total of 770 "Walruses" were built, which served in Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Turkey, Ireland, Portugal, Argentina and France. On average, "Walruses" served until the mid-50s. Argentine aircraft became the record holders, which served until 1958.

The "Walruses" left quietly and without splashes. Basically, they were simply disassembled and disposed of. Only two aircraft have survived to this day. One "Walras" is a collection from various parts of the museum in Yeovilton, the second - "Seagall Mk. V ", painted as" Walras ", is in the RAF Museum in Hendon.

This is the story of the Walrus Mk.I (II) aircraft. Marine reconnaissance aircraft, liaison aircraft, artillery fire spotter, light bomber, anti-submarine and rescue aircraft.

A few words about the construction.

One-legged biplane boat. Crew of three people: pilot, navigator, radio operator. The pilot and navigator sat in the cockpit, separated by a dashboard. The navigator sat in front, the pilot behind and above the navigator. This provided the pilot with excellent visibility. The navigator's cockpit was equipped with sighting and navigation equipment. Plus, the navigator was responsible for the front machine gun shooter. Behind the pilot's seat was the radio operator's cabin, who also played the role of the tail gunner.

The place in the fuselage between the radio operator's cabin and the tail turret was used to transport goods or people. Behind the stern machine gun was a rubber rescue boat for the crew.

The tail wheel was steerable and played the role of a rudder in the water.

The wings were similar in design. The difference was that the upper wing had fuel tanks, and the landing gear struts were removed in the lower wing.

The power plant consisted of a 9-cylinder air-cooled Pegasus II engine with a capacity of 635 hp. The aircraft of the second iteration were equipped with a more powerful 775 hp Pegasus IV engine. On all modifications of the boat, a wooden two-blade constant-pitch propeller was installed. The engine was started with compressed air.

"Walrus" could take off both from the water and from unprepared runways. Takeoff and landing on the ground was carried out using wheeled landing gear, which were retracted with a turn into the niches of the lower wing.

LTH Walrus Mk I

Wingspan, m: 13,97

Length, m: 11,58

Height, m: 5,13

Wing area, м2: 55,93

Weight, kg

- empty aircraft: 2 223

- normal takeoff: 3 334

Engine: 1 x Bristol "Pegasus VI" x 750 HP

Maximum speed km / h

- at sea level: 200

- at height: 217

Cruising speed, km / h: 153

Practical range, km: 966

Rate of climb, m / min: 244

Practical ceiling, m: 5 650

Crew, people: 3-4

Armament:

- one 7,7 mm machine gun in the bow;

- one 7,7 mm machine gun in the middle of the fuselage;

- bomb load weighing up to 272 kg on underwing bomb racks or 2 Mk VIII depth charges.

Information