Elbrus. Shelter 11. Capture story

prehistory

There was not much literature, but then the 90s arrived, and a wave of scientific and pseudo-documentary literature filled the shelves.

I bought everything and read what is called avidly.

In total, I met 5-7 versions of the capture of Shelter 11: from quite plausible,

but not proven, to the point of frankly absurd. And who was there to tell about it?

Our eyewitnesses who survived did not expand on this topic. Germans this history also did not paint from books.

In the absence of real details, the existing versions of this story were overgrown with mythology,

in which it all boiled down to one single real fact - Shelter 11 was actually captured by the company of Hauptmann Groth.

Everything else is a matter of faith, convictions and taste of those who got acquainted with different versions of the versions.

And in the second book "The Battle for the Passes" in a large section about the hostilities in the Elbrus region, I finally came across how this story actually looked. And no speculation.

Only documents and their author's analysis.

In order not to retell it in my own words, I will give a shortened version of the chapter on the capture of Shelter 11 from A. Mirzonov's second book “The Battle for the Passes. Another look. " With the permission of the author, of course.

I think it will be better this way, since the readers will be able to feel not only the author's presentation style, but also the order of his analysis of German documents.

Despite the number of versions regarding this combat episode, which are in circulation today in the literature and on the Internet, a healthy desire has appeared to deal with this issue as thoroughly as possible.

And, oddly enough, various inconsistencies (including very serious ones) that exist in the description of this event in the German military documents themselves prompted me to do this.

Somehow it turned out that before me no one had paid attention to these very inconsistencies. As a result, I would like to dot the and's in this story.

Cards

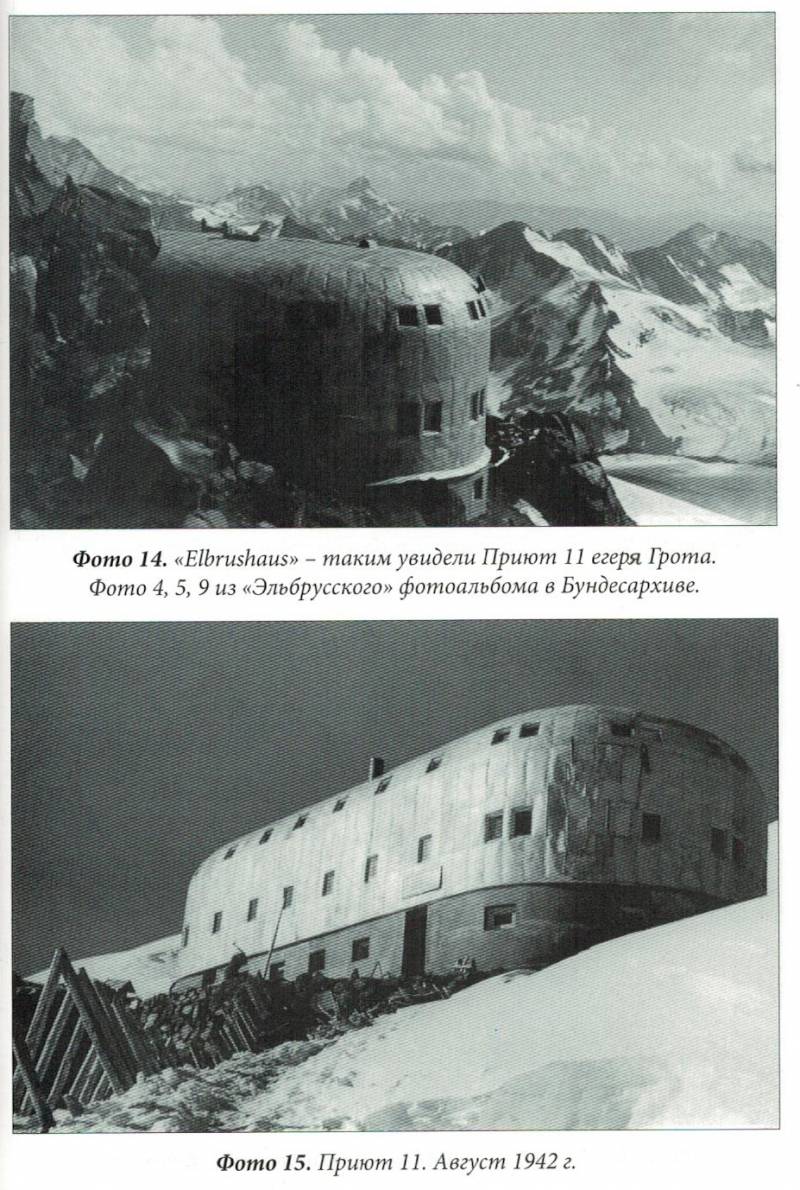

Military fate has not passed this unique object. The hotel was captured by the Germans and for several months became the main stronghold of the gamekeepers in the Elbrus region.

A fairly detailed description of these events is given by V. Tike in his work "March to the Caucasus ...".

If we ignore the distorted toponymic names and some points in the text that raise doubts, then everything is quite coherent and consistent. Those who wish can easily find on the net this book and the description of the capture of Shelter 11 in it.

I will cite one fragment of this description, which illustrates Grot's disappointment at the lack of shelters on the ground, indicated on his Russian map.

There was neither the Western Shelter, nor the Gastukhov Shelter. However, the shelter, marked at an altitude of 4100 meters, turned out to be a modern Intourist hotel with aluminum cladding, central heating and electric light. But he was at an altitude of 4200 meters and was converted into a barracks. In addition, at an altitude of 5300, on a narrow saddle between the eastern and western peaks of Elbrus, there was a plywood shed, which was filled with ice and could hardly be used as a shelter. Not far from the hotel, around the meteorological station of a solid building, there were several plywood houses.

Provided with such inaccurate maps and completely unaware of local conditions, Captain Groth with a signalman on August 17 at 3:00 went for Schneider's reconnaissance patrol in order to get intelligence data as soon as possible.

The rest of his small detachment was ordered to wait for the column of pack and (as soon as it arrived) to follow him.

At sunrise, Captain Grotto and his signalman were at the height of the Hotu-Tau pass (3546 meters). Before them lay the tongues of the Azau, Gara-Bashish, Terskol and Dzhika-Ugon-Kes glaciers stretching for 17 kilometers from west to east.

The grotto could not believe his eyes when in the middle of this weathered, icy desert, crossed by numerous faults, six kilometers away on a cliff (650 meters higher), he saw a hotel covered with metal, sparkling in the sun.

The attentive reader in this passage will notice that the Russian map at the Groth was the only one. The markings on it were inaccurate. The grotto had absolutely no knowledge of local conditions. And he saw Shelter 11 with amazement.

This is, as it were, not at all what we know in various completely documentary films about the war in the Elbrus region, idle filmmakers and their commentators.

By the way, no one thought about why these films are shot in the Elbrus region?

It is convenient to get here and it is very comfortable to live here. There is no need to strain in order to shoot an impressive nature for a film - the cable car will take you there. You can even look into the cracks on the glacier and shoot some kind of dugout. And in the evening in the hotel bar you can speculate about the war. There really was a war here.

Somehow, those wishing to tell the public about the heroic defense of the Caucasus do not reach either the Klych gorge, or the southern slopes of the Sancharo or Allashtraku passes, or the Mastakan pass. Far away, hard, cold and wet. No hotels for you, no cable cars.

And all would be fine, but the trouble is that such films slowly and surely drive into the mass consciousness a very one-sided and distorted idea of the military events in the mountains: the understanding that the fate of the Caucasus was decided in the Elbrus region.

As a rule, the authors of these films either heard little or did not know about another war in the mountains.

Meanwhile, if we go back to Hauptmann Groth, who necessarily appears in every such film (and in one of these films about the Grigoryants company, the name of Groth is mentioned more often than Lieutenant Grigoryants himself), no serious source has published any information about the pre-war Grot's stay in Russia, including his memoirs and comments of his son.

This small lyrical digression is actually not quite a digression.

What Tike wrote about was unexpectedly confirmed in one of the documents about these events.

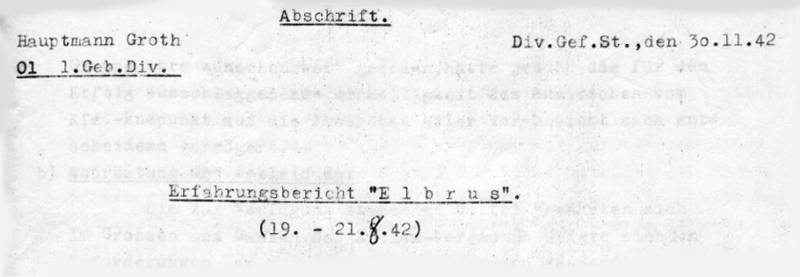

I will cite some excerpts from a document entitled Report on the Elbrus experiment 19.08.1942/21.08.1942/30 - 1942/XNUMX/XNUMX, compiled by Hauptmann Groth on November XNUMX, XNUMX.

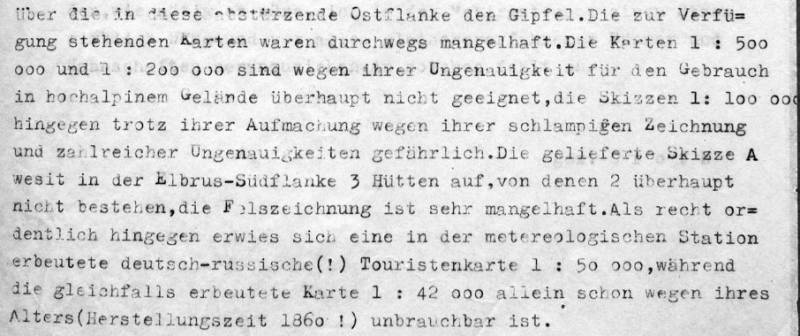

Maps 1: 500 and 000: 1, due to their inaccuracy, are generally not suitable for use in high-mountainous areas, while schemes 200: 000, despite their appearance (due to careless drawings and numerous inaccuracies), are dangerous.

The provided diagram A shows 3 huts (shelter) on the southern side of Elbrus, two of which are not available at all, the images are very imperfect.

But everything turned out to be correct and neat on the German-Russian tourist map of 1:50 000 captured at the meteorological station, while the captured 1:42 000 map turned out to be unusable only because of its age (year of issue 1860).

Such are the cartographic collisions. This was as a backstory to the takeover of Shelter 11.

Capture date

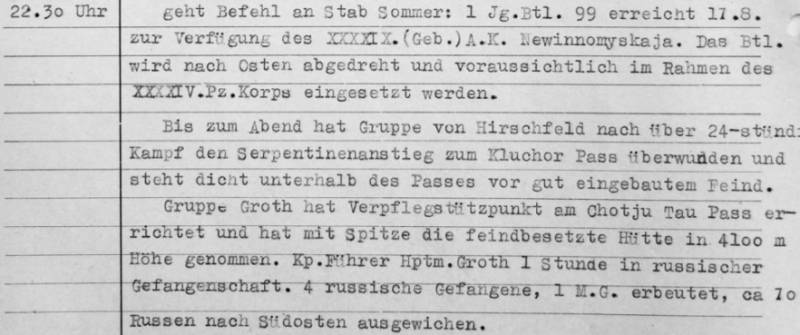

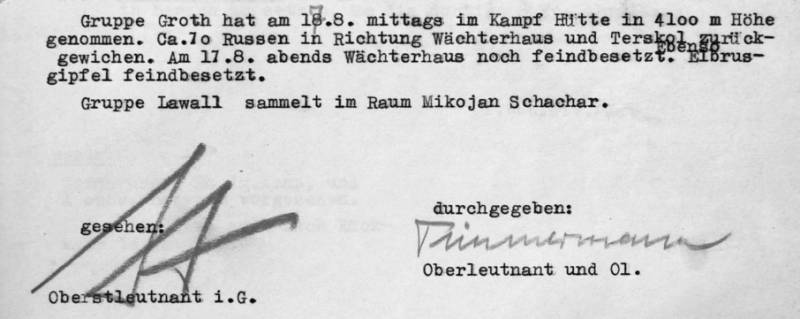

However, let us return to the previously cited entry in the combat log of the 1st Mountain Division, made on August 16, 1942 at 22:30.

Here is this journal entry (last paragraph).

Different authors in their studies give different dates for the capture of Shelter 11.

R. Kaltenegger in his book Gebirgsjager im Kaukasus gives the date 17 August.

The same Kaltenegger in his Weg und kampf der 1. Gebirgs-Division 1935-1945 writes that Shelter 11 was captured on 16 August.

V. Tike in his book “March to the Caucasus. Battle for Oil "gives the date of the capture of the Shelter on August 17.

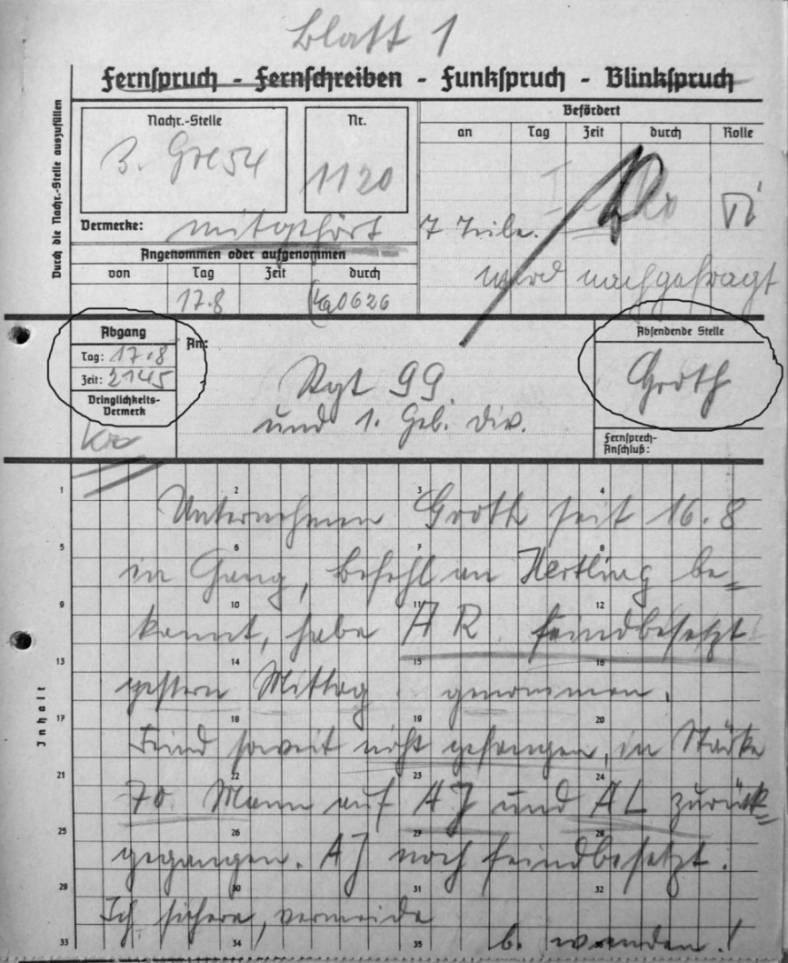

To clarify this conflict, it is high time to turn to Groth's message about the seizure of the Shelter, transmitted by a radiogram. Found in the Bundesarchive and such a unique document.

Such radio messages and telephone messages were filled in by the receiving signalmen at the points of contact on the pages of special notebooks, then they were torn off and passed on to the headquarters.

The easiest way would be to read the document and close the question. But the reading was just not all right. It is more appropriate here to talk about decoding. And the matter was not only in the individual peculiarities of the handwriting of the signalman, who filled out the form in the process of receiving the message by ear. The problem is that immediately after the war, a writing reform was carried out in Germany. And my several attempts to involve native speakers in the translation of such written documents have ended in nothing.

Nevertheless, unlike many other similar radiograms, this one was lucky. We managed to "pull out" the text by collective efforts.

I have circled the date and time the document was sent (on the left) and the name of the officer (on the right) from whose location the message was sent, in order to make it easier for the reader to navigate.

So, the document was sent on August 17 at 21:45 (Berlin time) to the 99th regiment and the 1st mountain division.

With understanding of the text, the following happened:

“Operation Grotto is in progress since 16 August, orders for Hartling have been received, AR occupied by the enemy is captured at noon.

The enemy ... not captured, by force (in composition) 70 people went back (retreated) to AJ and AL. AJ is still busy with the enemy. "

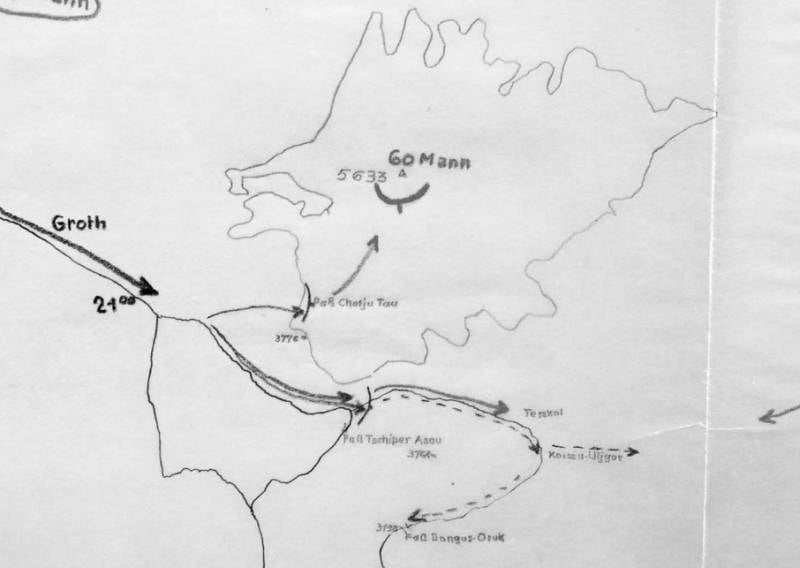

We look at the German map of the Elbrus region in the illustrations for the book.

Point AR - Hutte 4100 (aka Shelter 11), point AJ - Wachterhaus (Security House at Azau Glade), point AL - Terskol.

Well, there is also the date of August 16 and the Red Army unit of 11 people that left Shelter 70 in the direction of Polyana Azau and Terskol.

If any of the connoisseurs of the German language wants to throw a stone at me in this regard and thinks that deciphering such tablets is easy, then I can download it with such message forms in the hope of help.

There is still a lot of interesting things.

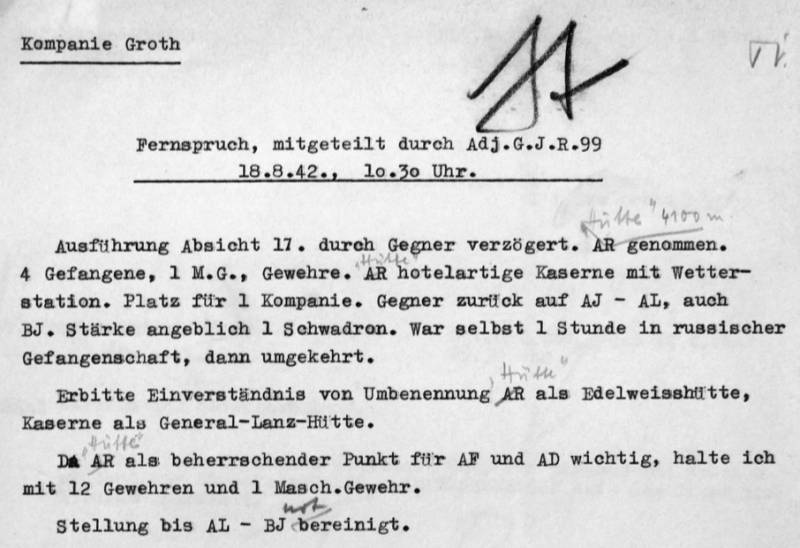

The next document is a telephone message from Groth's company to the 99GEP adjutant. Submitted on 18.08.1942/10/30 at XNUMX:XNUMX.

Presumably 1 squadron. Was himself 1 hour in Russian captivity, then vice versa.

Please agree to rename the AR as "Edelweisshütte", the barracks as "General Lanz-hütte".

AR is important as the dominant point for AF and AD, I hold (it) with 12 rifles and 1 machine gun.

Positions before AL - BJ are not settled. "

Here the composition of the retreating Red Army men is indicated in the squadron (company), it is as if not that 70 people, but more.

Probably, Grotto loved his commander, and immediately proposed to rename the Shelter.

And the composition of the Grotto reconnaissance group is also visible. Judging by the number of weapons, no more than 15 people.

And here is another document.

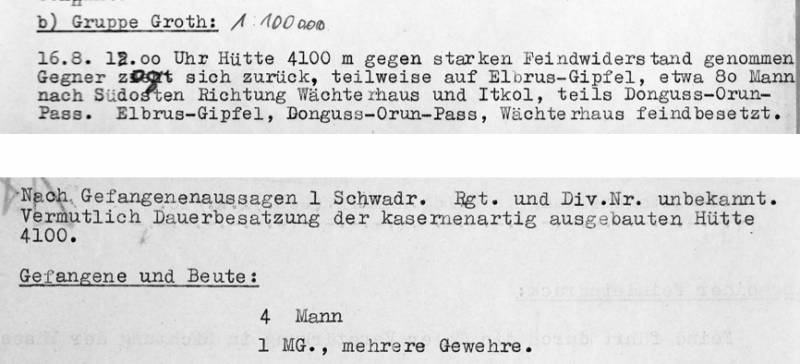

Noon message from the headquarters of the 1st mountain division to the 49th mountain corps on August 18, 1942.

Here the printed date of August 18 is forwarded to August 17.

True, it is indicated here that the Shelter was captured in battle, and about 70 Russians retreated.

In order to understand in more detail the details of the capture of the Shelter, let us turn to the "Elbrus" folder in the Bundesarchive, which contains the documents on the ascent of the huntsmen to Elbrus.

In this case, we will not be interested in the ascent itself, but in some details of the seizure of Shelter 11, which remained outside the scope of the compressed reports presented, but ended up in several more detailed documents of the Elbrus folder.

So, the first document is the report of the refereeor Mang dated 05.09.1942/XNUMX/XNUMX.

"We conquered them Elbrus!", Prepared for the press, but at the same time passed through the intelligence department of the headquarters of the 1st mountain division:

The key point in the ascent and mastery of the Elbrus summit was the Southern Shelter, located at a dominant height in the middle of the ice. Meanwhile, news appeared that from the opposite side of the valley occupied by the enemy, Bolshevik forces were advancing in the direction of the German positions.

It was necessary to take security measures and bring the troops to combat readiness.

Captain Groth, who single-handedly intended to make a dash to the South Shelter, had (moreover) to establish whether he was occupied by the Russians.

Captain Groth went to the orphanage, from where (at his waving his handkerchief) two envoys came out to meet him.

In the house itself they had 3 officers and 6 more people.

With great difficulty, Captain Groth made it clear to the Russians that they were surrounded and trapped.

The Russians, however, did not react to this and took Captain Groth prisoner.

From subsequent conversations between officers and soldiers, it became clear that the Russians were going to take Captain Groth to their own shortest route.

When the three officers descended first, Captain Groot seized the opportunity to capture the remaining soldiers and immediately call for reinforcements.

Thus, thanks to his decisive actions, it was possible to seize the shelter.

The Southern Shelter itself (a massive building built to meet the requirements of aerodynamics) was the highest mountain meteorological station in the Soviet Union.

It was built in accordance with the most modern provisions of architecture, and part of the work on its construction was not even completed.

Adequately constructed living quarters with central heating and electricity for soldiers were in short supply. As well as high quality mountaineering uniforms, ample supplies of food and weapons, which were considered welcome trophies.

This once again showed the importance of this stronghold with its dominant height from which it was possible to control all the roads in the district.

The occupation of the Southern Shelter made it possible to remove the security personnel and place people in the building. "

Here, as we can see, there is a date of August 16, but there is no information about 70 Russians who left the Shelter.

In another report by the re-freighter Zwerger from 13 company 98 GEP entitled "The Conquest of Elbrus" dated 28.08.1942/XNUMX/XNUMX (the re-freighter was part of the ascent group) gives a more detailed picture of events at the Shelter.

By the way, the report is also written in the form of a press diary.

In the afternoon we reach the Elbrus-Vostochny shelter, which our captain was especially eager to master.

With one weak infantry outpost, he moved forward to the shelter and found that it was still occupied by the Russians.

Alone, he approached two sentries with rifles, they were two huge guys from the Pamirs, wanted to shake hands with them, but they did not appreciate this noble gesture and took him prisoner - to two Russian officers.

Having briefly greeted the Russians, the captain briefly informed them that they were surrounded and would still be captured, since there were a lot of German soldiers around, although we were few and we were forbidden to shoot.

Two Russian officers thought that it would be best to get out, but ordered the Asians to take our captain to the Baksan valley. While both officers had disappeared, he went under escort to the meteorological station located a little higher, the present Edelweiss shelter, where he saw a whole mountain of cakes and pies on the table.

To the question - whose it is, the guards answered: officers. Then they invited our captain to sit down and have a snack together.

They also didn't make them invite themselves twice, sat down with their rifles between their knees, and leaned on as if they hadn't eaten anything good in life.

Our captain explained to them that now he is in command here. And they can quit weapon and help us, the war will end for them. At first they looked a little puzzled. But then (with a grin) they really piled rifles and a machine gun into the corner. Then our captain left the shelter, waved a white handkerchief - and our small detachment was able to take possession of a large house at an altitude of 4200 m without a single shot. Today we are tired, and the vacuum made it difficult to sleep.

But before I crawl into my sleeping bag, I look at the peaks that rise to dizzying heights under the eternal stars - the great life of the mountains reigning over everything.

And before falling into a dream, I think about the great happiness that fell to me as a German soldier, a mountain shooter, to participate in this mountain trip, which will go down in history, to feel like a German climber in full force. "

This document also indicates the date of August 17, and again nothing is mentioned about 70 Russians. Oddly enough, the least detailed information about these events is contained in the report of the Grotto himself entitled "Report on the ascent of Elbrus with the help of a high-altitude company of the 1st mountain division", compiled at the Shelter 11 on 26.8.1942.

In the shelter on the southern foothills of the Elbrus-Vostochny peak, there were three officers and eight soldiers.

According to the readings of the altimeter, the shelter was located at an altitude of 4200 m, which ensured a dominant position over the entire glacial basin and exits to the eastern passes.

They managed to take possession of them easily, while part of the enemy garrison was captured, some were put to flight.

Immediately after the lesson, the shelter received the name "General Lanz - House", by analogy with the previously named weather station "Shelter" Edelweiss ".

Again the date is August 17 and again nothing about the 70 Russians, about whom Grot wrote in his reports after the capture of the Shelter.

Well, in conclusion, an excerpt from the report on the combat activities of a high-altitude company dated August 22, a document without a signature.

When he was evacuated to Tegenekli, he managed to capture the guards and capture AR.

The rest of the enemy fled in the direction of the Baksan valley.

Trophies were taken: food, equipment, uniforms, weapons, 4 enemy soldiers were captured.

AR is a complex of several buildings, including the Intourist hotel, a weather station and a radio station, turned into barracks. "

Regarding which unit of the Red Army was stationed at Shelter 11 at the time of the capture, interesting information was found in the combat log 214 kav. shelf (spelling preserved):

On 17.08.1942/XNUMX/XNUMX, an enemy reconnaissance group was found in the indicated direction, which, taking advantage of the oversight of the patrol, captured the patrol as part of the station. Sergeant Sterlikov and two soldiers with a light machine gun.

Khasanov returned to the starting point. "

By the way, the next day, during a clash during reconnaissance from the CDKA in the direction of Glade Azau

The date here is also August 17th. In the German version there are four prisoners, and a machine gun in a row.

Consequently, Sergeant Sterlikov and the soldiers who "made a mistake" in eating pies together with Hauptmann Groth were captured at Shelter 11. But what about the 70 Red Army soldiers who left the Shelter without a fight? Nothing about them here either.

Conclusions by date

Let's try to undermine the available information. First by date.

Still, according to most documents, it all boils down to the fact that Shelter 11 was taken by the rangers on August 17. BUT!

Who would explain how the information about the capture of the Shelter appeared in the combat log of the 1st Mountain Division on August 16 at 22:30?

This is more than a serious document, in which information, with the existing quality of communication with the subdivisions, was entered practically in real time.

If we were talking about the logs of combat actions of any of the Red Army divisions that fought in the Caucasus, then I would simply assume that the information could be entered retroactively: such logs could not be filled even for weeks, and in some divisions they were not kept at all.

And leapfrog with dates when filling out such journals retroactively was commonplace.

But in the magazines of the 1st and 4th mountain divisions of the Wehrmacht, such a situation is simply unthinkable, the pedantry in filling them is frankly amazing.

And I cannot explain this collision with the date of the capture of Shelter 11. However, with the passage of time, this circumstance, of course, no longer affects anything.

70 people

Much more interesting is the question of whether or not there was a Red Army unit in the amount of about 11 people at Shelter 70 at the time of its capture, as indicated in the reports of Groth immediately after the events, as well as in the divisional reporting documents?

Indeed, in all the official reports to the high command of the army and to the press, there is not a word about this not only from Groth, but also from other participants in the events.

In these reports, the composition of the Russians at the Shelter had already been reduced to 3 officers and 6 (8) soldiers, four of whom were captured.

Moreover, such a number of defenders of the Shelter is not confirmed by the documents of the Red Army.

I would venture to note that the Germans in this case could have their own reasons not to advertise information about the soldiers of the Red Army who left the Shelter: neither the high authorities nor the readers of the German press would understand the fact that 70 Russians were released just like that, but not taken prisoner. Moreover, against the background of victorious reports about the ascent of Elbrus.

In my opinion, this is precisely why this fact is not reflected in any way in German documents for high authorities and the general public.

And what about the information in the documents 214 kav. regiment of the Red Army, in which only a group of scouts of 10 people is mentioned at the Shelter? I believe that the command of the 214th regiment could also have very good reasons for not reflecting in the documents the abandonment of the Shelter without a fight and the retreat without an order down.

Let me remind you that at that time, order No. 227 of the People's Commissar of Defense of the USSR I. V. Stalin of July 28, 1942 was already in full force.

or in common parlance

And the detachments acted, and the commanders who made a retreat without an order were shot. This was the harsh reality of the day.

But all this, so to speak, is just my conclusions.

But if you still ask me: "Were these 70 Red Army men at the Shelter or not?" I will answer in the affirmative.

And it's not just Groth's handwritten report. I don't think he would have ascribed such a victory to himself in the presence of a large number of witnesses from among his soldiers and officers.

There is one more essential, in my opinion, circumstance that confirms me in this conviction.

Pay attention to an interesting fact, repeatedly reflected in various German reports: there were 3 Red Army officers at the shelter at the time of the capture.

Three officers for 6 soldiers is an unimaginable ratio for reconnaissance or defense of the Shelter.

With a severe staff shortage for the officers that existed in parts of the Transcaucasus, when even junior lieutenants were sometimes put in command of the battalion, such a situation, in my opinion, is simply impossible.

But 3 officers for almost a company is quite normal.

Well, a considerable amount of food, ammunition, uniforms and equipment seized at the Shelter, which the Germans write about, is also a bastard in the same line.

And the last.

Here is a tracing paper from a two-kilometer map of the Elbrus area for August 16-18 from the documents of the intelligence department of the headquarters of the 1st mountain division.

On it to the south of the Elbrus peak in the area of Shelter 11, the position of the Red Army is indicated in red with the inscription “60 people”.

Serious people served in the intelligence department. And they did not eat their bread in vain.

So there were more than two Red Army platoons at Shelter 11 at the time of its capture. Here Hauptmann Groth has nothing to reproach.

When the book was already being prepared for publication, the next archival excavations produced one interesting document from the headquarters of the 49th Mountain Corps of the Wehrmacht, which is directly related to the history of the capture of Shelter 11.

Here are excerpts from it:

[/ Center]

[/ Center]

[/ Center]Final conclusion

Nevertheless, the capture of Shelter 11 took place on August 16. Despite the fact that it was guarded by almost a company of Red Army men (70-80 people) from 1 squadron of 214 cavalry. regiment, which ceded Shelter 11 without a fight to about fifteen German mountain rangers.

Now you can put an end to this story.

I wonder why the huntsmen did not burn Shelter 11 when they left the Elbrus region?

But they could.

However, this sad fate did not pass over many years later.

Note. Photo scans are provided by A. Mirzonov and are published with his permission.

Information