The Warsaw Matins of 1794

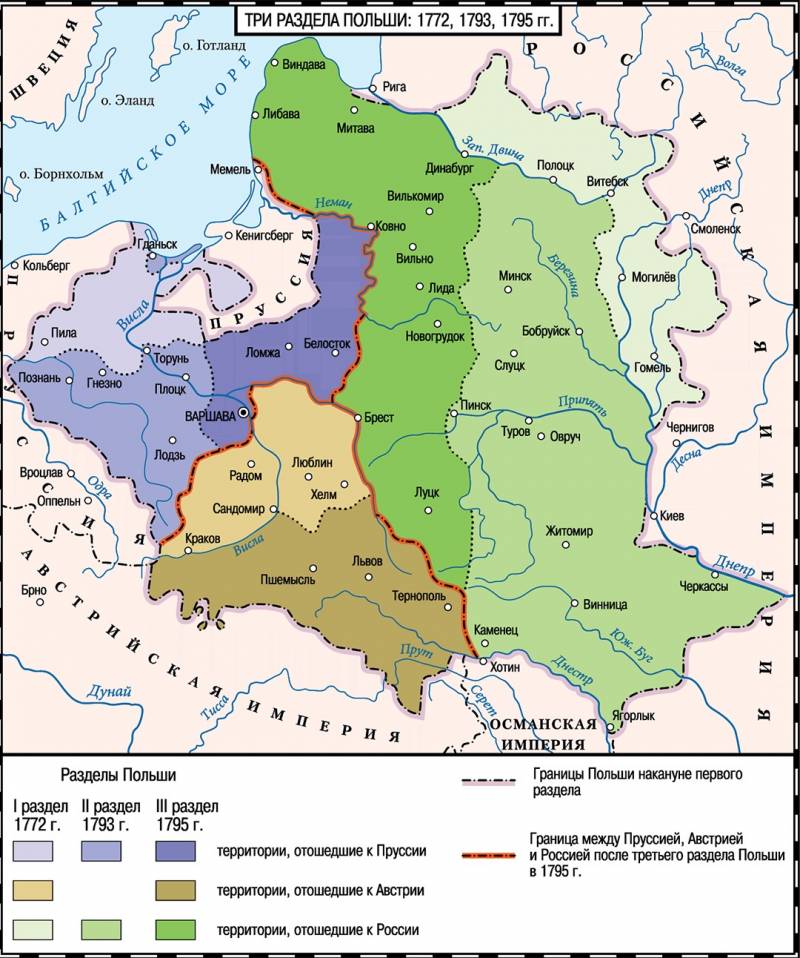

In two articles brought to your attention, we will talk about the tragic and sad events that occurred in Poland in 1794. The rebellion, led by Tadeusz Kosciuszko and accompanied by the massacre of unarmed Russian soldiers in the churches of Warsaw ("Warsaw Matins"), ended with the assault on Prague (the outskirts of the Polish capital) and the third (final) division of this state between Russia, Austria and Prussia in 1795. The emphasis, of course, will be placed on Russian-Polish relations, especially since then there were interconnected tragic incidents, called the Warsaw Matins and the Prague Massacre.

The first article will talk specifically about the "Warsaw Matins", which occurred on Easter Thursday, April 6 (17), 1794. The events of this day are little known in our country, attention has never been focused on them, especially in Soviet times. That is why for many, this story may seem especially interesting.

"The eternal dispute of the Slavs"

Mutual claims and grievances of Poland and Russia have long-standing history. Neighbors for a long time could not decide on the degree of kinship, or on the size of the controlled territory. This was reflected in Russian epics, where some characters marry girls from the "Lyashsky land", and the hero of the epic "Korolevichi from Kryakova" is called the "hero of the Holy Communion of Russia." But even real dynastic marriages sometimes led to war - like the marriage of Svyatopolk (the “Cursed” son of Vladimir Svyatoslavich) to the daughter of the Polish prince Boleslav the Brave, who later fought on the side of his son-in-law against Yaroslav the Wise.

Perhaps, the main reason for the Polish hostility should be recognized as the failed imperial ambitions of the Commonwealth.

Indeed, at the peak of its power, this state was a real empire and, in addition to the Polish regions, also included the lands of modern Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia and Moldova.

The Polish Empire had a chance to become a powerful European state, but it collapsed literally in the eyes of its contemporaries, not at all surprised by its fall. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth not only lost the territories once conquered, but also lost its statehood, which was restored only in the XNUMXth century - by decision and with the consent of the Great Powers. The main reason for the fall of the Commonwealth was not the strength of the neighbors, but the weakness torn by internal contradictions and poorly managed Poland. Political short-sightedness, bordering on the inadequacy of many Polish political figures of those years, including those now recognized as national heroes of Poland, also played a role. In conditions when only peace and good relations with neighbors gave at least some hope for the continued existence of the Polish state, they went to confrontation for any reason and began hostilities in the most adverse conditions for them.

On the other hand, the brutal oppression of Orthodox Christians, Uniates, Protestants, Jews and Muslims (who also lived in the territory of this country) declared by people of the "second grade" led to the fact that the outskirts simply did not want to be Polish provinces anymore.

A. Starovolsky, who lived in the XVII century, argued:

Finally, the principle of the “golden liberty”, “Henrykus articles” (a document signed by Heinrich Valois, who also managed to visit the Polish throne), liberum veto, adopted in 1589, which allowed any nobleman to stop the Sejm, and the right to “rokoshi” - creation Confederations waging an armed struggle against the king, in fact, made the central government incapable.

It was impossible to save their state in such conditions. But the Poles have traditionally blamed and blame the neighbors for all the troubles, primarily Russia. These claims against Russia seem especially strange when you consider that during the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the XNUMXth century, primordially Polish lands were transferred to Prussia and Austria-Hungary, while Russia received areas where the vast majority of the population was Ukrainian, Belarusian, Lithuanian and even of Russian origin.

Polish state in 1794

One of the episodes of the "national liberation struggle", perhaps the most destructive for Polish statehood (but it is traditionally proud in Poland), was the military campaign of 1794. It entered the history of Poland as Insurekcja warszawska (Warsaw Uprising). On marble slabs near the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Warsaw, two episodes of this inglorious war for Poland are mentioned as “great victories” along with the capture of Moscow in 1610 and Berlin in 1945 (yes, without the Poles, the Soviet Army, of course, would have been in Berlin failed), and the "victory at Borodino" in 1812.

They tried not to recall politically correct events in the USSR. Meanwhile, in Russian historiography, the central event of the uprising of 1794 was called the "Warsaw Matins" and the "Warsaw Massacre" - and these official terms say a lot.

The fact is that since 1792, foreign military garrisons were deployed in large cities in Poland. Since they stood there with the consent of the Polish government and King Stanislav Poniatowski, these troops could not be called occupying. Otherwise, for the same reason, we can now call the American troops occupying in modern Poland. The commanders of foreign units did not interfere in the internal affairs of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but the very presence of foreign soldiers caused strong irritation in Poland.

Russian troops in Poland were then led by Lieutenant General Baron Osip Igelstrom. In love with the Polish Countess Honorata Zalusskaya, he paid little attention to "gossip" about the upcoming anti-Russian speech.

On the other hand, Catherine II did not attach any importance to reports of the troubled situation in Poland. The empress hoped for the loyalty of her former lover - King Stanislav Ponyatovsky. Thus, the responsibility for the tragedy in Warsaw and Vilna lies with her shoulders.

Tadeusz Kosciuszko, a native of a rather poor Lithuanian family, whom schoolmates from Warsaw Knight School (studied from 1765 to 1769) was nicknamed “Swede”, was elected the leader of the new rebellion (recall that the king and the Polish government did not declare war on anyone). By this time, Kosciuszko had the U.S. Independence War, in which he fought on the side of the rebellious colonists (and rose to the rank of brigadier general) and military operations against Russia in 1792.

On March 12 (according to the Julian calendar) the Polish Brigadier General A. Madalinsky, who, according to the decision of the Grodno Seim, was to disband his brigade, instead crossed the Prussian border and seized the warehouses and treasury of the Prussian army in the city of Soldau. After this act of robbery, he went to Krakow, which was surrendered to the rebels without a fight. Here Kosciuszko March 16, 1794 was proclaimed the "dictator of the Republic." He arrived in the city only a week later - on March 23, announced the “Act of Rebellion” on the market square and received the title of Generalissimo.

The size of Kosciuszko’s army reached 70 thousand people, however, the armament of most of these fighters left much to be desired.

They were opposed by Russian troops numbering about 30 thousand people, about 20 thousand Austrians and 54 thousand Prussian soldiers.

Uprising in Warsaw and Vilna

On March 24 (April 4 according to the Gregorian calendar), the Kosciuszko army near the village of Raclawice near Krakow defeated the Russian corps, led by Major General Denisov and Tormasov. This, in general, insignificant and not having strategic importance victory served as a signal for an uprising in Warsaw and some other large cities. In the Polish capital, the rebels were led by a member of the city magistrate, Jan Kilinsky, who, on his own behalf, promised the Poles the property of the Russians living in Warsaw, and priest Jozef Meyer.

The success of the rebels in Warsaw was greatly facilitated by the inadequate situations of the Russian command, which did not take any measures to prepare for a possible attack on its subordinates.

Meanwhile Igelstrom was well aware of the hostilities opened by Kosciuszko and his associates. Rumors of an impending march in Warsaw were known even to the rank and file and officers of the Russian garrison, and the Prussian command withdrew its troops outside the city in advance. But Igelstrom did not even give the order to strengthen the protection of the arsenal and armory warehouses. L. N. Engelhardt recalled:

And F.V. Bulgarin claimed:

But, again, the Russian command, headed by Igelstrom, did not even take the slightest precaution, and on April 6 (17), 1794 (Maundy Thursday of Easter Week), the ringing of bells informed the townspeople about the beginning of the rebellion. As Kostomarov later wrote:

As a result, many Russian soldiers and officers who came to the churches unarmed were immediately killed in churches. So, practically in full force, the 3rd battalion of the Kiev Grenadier Regiment was destroyed. Other Russian servicemen were killed in the houses where their apartments were located.

To quote Kostomarov once again:

The Russian writer (and Decembrist) Alexander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky in his essay “An Evening on the Caucasian Waters in 1824”, referring to the story of a certain artilleryman, a participant in those events, writes:

In the picture above, “noble insurgents” are selflessly and openly fighting against armed “invaders”. Meanwhile, N. Kostomarov described what is happening:

All this is very reminiscent of the events of Bartholomew’s Night in Paris on August 24, 1572, is not it?

It is estimated that in the first day 2265 Russian soldiers and officers were killed, 122 wounded, 161 officers and 1764 soldiers who were unarmed were captured in churches. Many of these soldiers were later killed, already in prisons.

Got to civilians. Among others, the future nanny of Emperor Nicholas I Evgeny Vecheslov was in Warsaw. She recalled:

One major of Polish artillery managed to take Mrs. Chicherina to the arsenal; and I, having two children in my arms, showered with a hail of bullets and shell-shocked in my leg, fell unconsciously into the ditch with the children, on dead bodies. ”

Then Vecheslov was also taken to the arsenal:

Other "prisoners of war" were the pregnant Praskovya Gagarina and her five children. The husband of this woman, the general of the Russian army, like many other officers, was killed by the Poles in the street. In a letter, the widow personally addressed Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who would later be called the “last knight of Europe” in Poland, and, referring to her pregnancy and distress, asked to let her go to Russia, but received a categorical refusal.

The commander of the Russian troops, General Igelstrom, fled from Warsaw under the guise of the servant of his mistress - Countess Zalusskaya, leaving a lot of papers in his house. These documents were captured by the rebels and served as a pretext for reprisal with all the Poles mentioned in them. Catherine II, who also did not pay attention to the information about the impending rebellion coming to her, feeling guilty, later refused to bring the unlucky general to court, limiting herself to his resignation. According to numerous rumors, she expressed her contempt for the Poles who showed such treachery, making the throne of this country the seat of her "night vessel." It was on him that she allegedly had an attack that caused death.

Some soldiers of the Russian garrison still managed to break out of Warsaw. Already quoted by L. N. Engelhardt testifies:

And on the night of April 23, rebels attacked the Russians in Vilna: due to the surprise of the attack, 50 officers were captured, including the commandant of the garrison, Major General Arseniev, and about 600 soldiers. Major N. A. Tuchkov gathered the escaped soldiers, and took this detachment to Grodno.

Tadeusz Kosciuszko completely massacred the massacre of unarmed Russian soldiers and defenseless civilians in Warsaw and Vilna. Jan Kilinsky from Warsaw (who personally killed two Russian officers and a Cossack during matins) received the rank of colonel from him, and Yakub Yasinsky from Vilno even the rank of lieutenant general.

These are the victories that the modern Poles considered worthy of perpetuation on the marble slabs of the memorial of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

But the subsequent actions of the Russian troops that came to Warsaw were considered by the Poles a monstrous crime.

Further events, which are traditionally called the Prague Massacre in Poland, will be described in the next article.

Information