Tablets from Vindolanda. Roman soldiers wore underpants!

Exodus 39: 30

Ancient writings tell. In our last article about excavations in Vindoland, we talked about finding there wooden signs that became the oldest written monuments in the UK. To date, more ancient tablets have been found, the so-called Bloomberg tablets. But we’ll talk about them some other time. And today, let the tablets from Vindolanda tell us about their contents, because they are a very rich source of information about life on the northern border of Roman Britain.

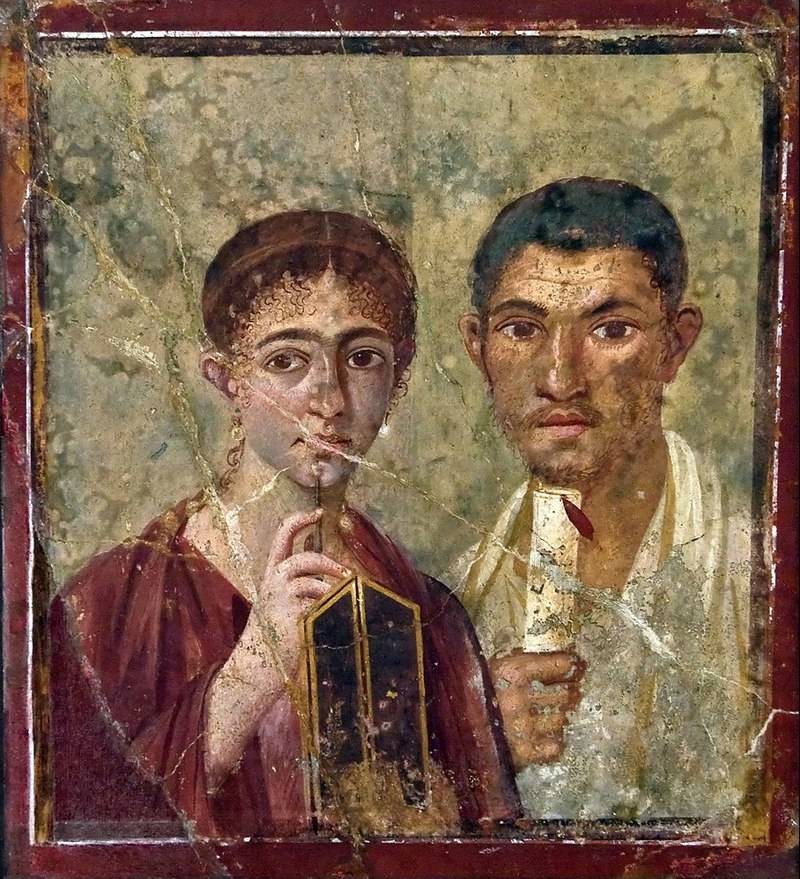

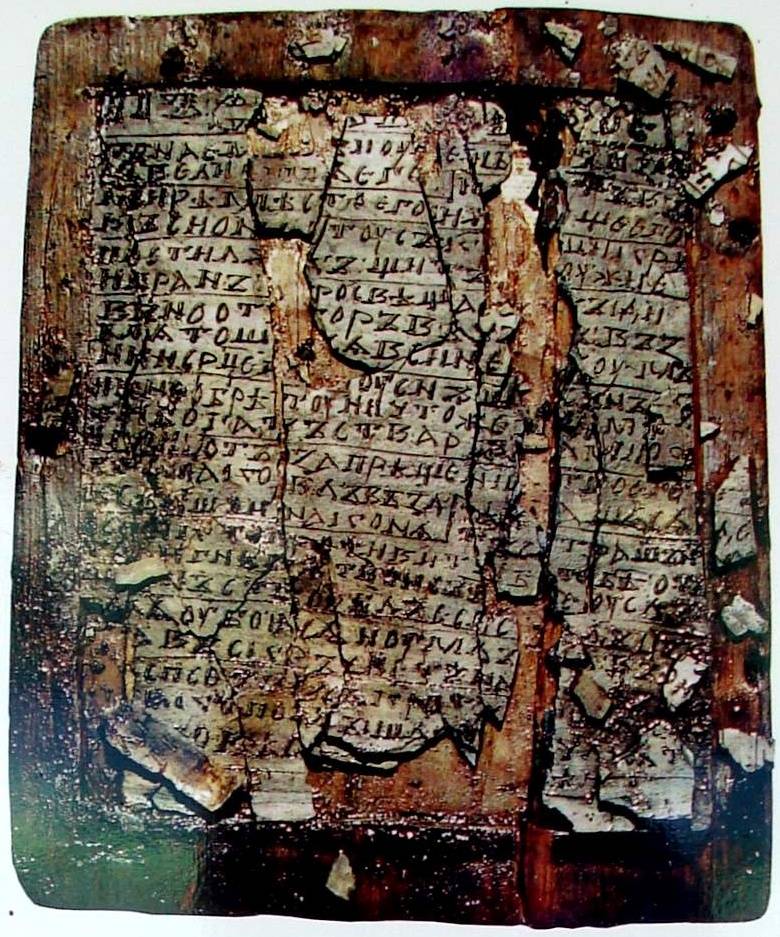

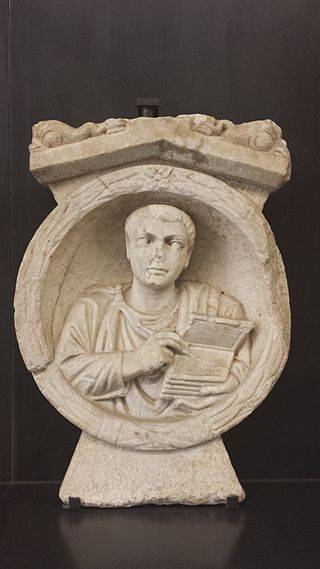

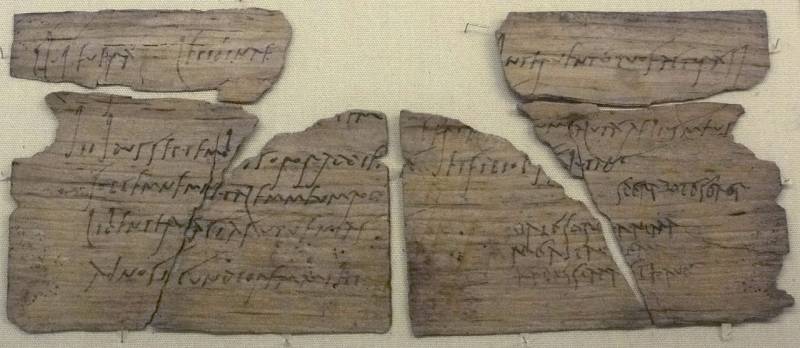

They look like this: these are thin wooden plates the size of a postcard, on which the text is written in black ink. They are dated I-II centuries of our era (that is, they are contemporaries of the construction of the wall of Hadrian). Although papyrus records were known from finds elsewhere in the Roman Empire, wooden ink-plaques were not found until 1973, when archaeologist Robin Birli discovered them in Vindoland, a Roman fort in northern England.

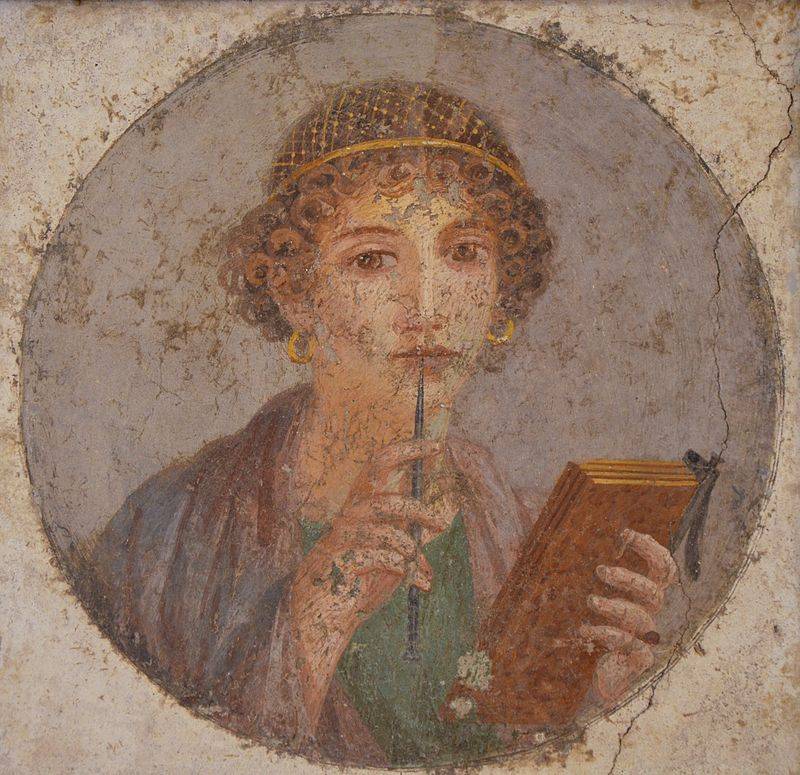

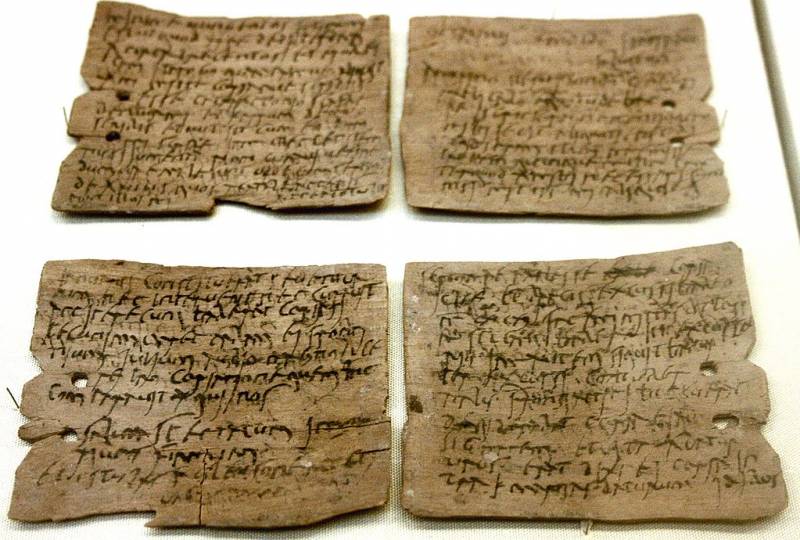

Like the texts of the Novgorod birch bark letters, the texts of these tablets are completely unstructured, that is, they are random in nature. There are texts related to the life support of the fort, there are personal messages to the soldiers of the Vindolanda garrison, their families and slaves. They even found an invitation to some lady’s birthday party. The party took place around 100 AD, so this text is probably the oldest document that has been preserved to our time, written in Latin by a woman.

Almost all the plates are kept in the British Museum, but some were still on display in Vindoland. The texts of 752 tablets were translated and published in 2010. Moreover, the finds of tablets in Vindoland are still ongoing.

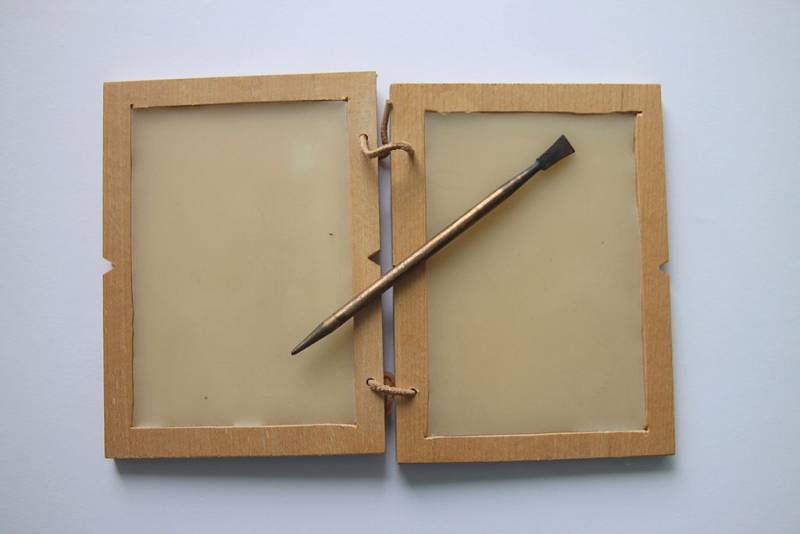

The wooden tablets found in Vindoland were made of different types of wood: birch, alder and oak, which grew here. But the stylus tablets, which were also found and which were intended for writing with a metal stylus on wax, were imported goods and were not made of local wood. The thickness of the plates is 0,25–3 mm, a typical size is 20 × 8 cm (the size of a modern postcard). They were folded in half, with an inscription to the inscription, and the ink was black, gum arabic and water. In the 1970s and 1980s alone, about 500 such tablets were dug, all thanks to the local oxygen-free soil in which the wood could be stored without decomposition.

The first records discovered in March 1973 were delivered to the epigraphist Richard Wright, but the quick oxygenation of the tree led to the fact that they turned black and became unreadable. Then they were sent Alison Rutherford to the University of Newcastle School of Medicine for multispectral photography. Photographs were taken in infrared light, on which the text was first made out. But the result was still disappointing, since the texts at first could not be deciphered. And the reason was simple. None of the researchers simply knew this form of handwriting! However, Alan Bowman from the University of Manchester and David Thomas from the University of Durham were able to decrypt it.

Fort Vindolanda served as the base for the garrison before the construction of the Adrian wall, but most of the plates are somewhat older than the wall, which was started in 122 AD. In total, five periods were identified in the initial stories of this fort:

1. approx. 85–92 AD, the first fort was built.

2. approx. 92–97 AD, the fort was expanded.

3. approx. 97–103 AD, further expansion of the fort.

4. approx. 104–120 AD, a break and re-occupation of the fort.

5. approx. 120-130 years AD, the period when the wall of Hadrian was built.

It turned out that the tablets were made in periods 2 and 3 (c. 92–103 CE), and most were written before 102 AD They were used for official records of cases at the Vindoland camp and for the personal files of officers and their households. The largest group of texts refers to the correspondence of Flavius Cerialis, prefect of the ninth cohort of the Batavians and his wife Sulpicia Lepidina. Several labels contain records of merchants and contractors. But who they are is not clear from the tablets. For example, a certain Octavian, the author of plate No. 343, is clearly a trader because he is engaged in the sale of wheat, hides and tendons, but all this does not prove that he is a civilian. He could well be one of the officers of the garrison, and even an ordinary.

The most famous document is the tablet number 291, written about 100 AD Claudia Severa, wife of the commander of a nearby fort, Sulpicia Lepidine, who contains her invitation to a birthday party. An invitation is one of the earliest known examples of a woman writing Latin text. It is interesting that on the tablet there are two styles of handwriting, with most of the text written with one hand (most likely, a housewife), but with a final greeting, apparently personally added by Claudia Severa herself (in the lower right part of the tablet).

The tablets are written in Latin letters and shed light on the literacy rate in Roman Britain. One of the tablets confirms that Roman soldiers wore underpants (subligaria), and also indicates high literacy in the Roman army.

Another small discovery concerned how the Romans called Aboriginal people. Before opening the tablets, historians could only guess if the Romans had any nickname for the British. It turns out that there was such a nickname. The Romans called them Brittunculi (short for Britto), that is, "little Britons." We found it on one of Vindolanda's tablets, and now we know what a derogatory or patronizing term was used in the Roman garrisons, which were based in Northern Britain, to describe the locals.

The originality of the texts from Vindolanda lies in the fact that they seem to be written in letters other than the Latin alphabet. Unusual or distorted forms of letters or extravagant ligatures, which can be found in Greek papyruses of the same period, are rarely found in the text, they are simply written in a slightly different way. Additional problems for transcription are the use of abbreviations such as “h” for a person (human), or “cos” for a consularis (consular), and the arbitrary separation of words at the end of lines due to the size of the plates.

On many tablets, the ink is very faded, so in some cases it is impossible to distinguish between what was written. Therefore, you have to turn to infrared photographs, which give a much more legible version of the writing than the original tablets. However, photographs contain marks that look like written, but they are not letters; in addition, they contain a lot of lines, dots and other dark marks that were not written. Therefore, some signs had to be interpreted in a very subjective way, based on the general sense of what was written.

Among the texts there are many letters. For example, the cavalry decurion Masculus wrote a letter to the prefect Flavius Cerialis with a question about the exact instructions for his people the next day, including a polite request to send more beer to the garrison (which had consumed the entire previous beer supply). It is not clear why he did not do this verbally, but apparently a certain distance had cut them off, and the affairs of the service prevented them from meeting. The documents contain a lot of information about the various responsibilities that men performed in the fort. For example, they had to be bathhouse keepers, shoemakers, construction workers, plasterers. Among the people assigned to the garrison were doctors, cart and furnace rangers, and stoker bath attendants.

In addition to Vindolanda, wooden plaques with inscriptions were found in twenty Roman settlements of Great Britain. However, most of them were stylus tablets to write on their wax-covered pages.

The fact that the letters were sent from different places on the Adrian wall and beyond (Katerik, York and London) makes us ask why they were found in Vindoland more than in other places, but it is impossible to give an unambiguous answer. The fact is that the anaerobic soils found in Vindoland are not unique. Similar soils are found in other places, for example, in some areas of London. Perhaps, because of their fragility in other places, they were mechanically destroyed during excavations, because these "pieces of wood" simply did not attach importance.

Today the tablets are kept in the British Museum, where their collection is exhibited in the gallery "Roman Britain" (Hall 49). They were included in the list of British archaeological finds selected by experts from the British Museum for the documentary Our Ten Treasures (BBC Television, 2003). Viewers were asked to vote for their favorite artifacts, and these tablets took first place among all the others.

Information