Manchu five-year plan of the Japanese military

This part stories World War II is little known due to the almost complete absence and rarity of literature, especially in Russian. This is the military economic development of Manzhou-Guo, a state formally independent, but actually controlled by the Japanese, or, more precisely, the command of the Kwantung Army. The Japanese captured a very large part of China, a kind of Chinese Siberia, with booming agriculture and agrarian resettlement from other provinces of China, and conducted industrialization there.

The industrialization of Manchuria was carried out, of course, in the interests of the Japanese military. However, its methods, goals, and general appearance were so similar to industrialization in the USSR that research on this topic was clearly not encouraged. Otherwise, it would be possible to get to the interesting question: if Soviet industrialization was for the people, and Manchu was for the Japanese military, then why are they so similar?

If we abandon emotions, then it should be noted: two extremely similar cases of industrialization of territories previously underdeveloped in industrial terms are of great scientific value for the study of the general laws of initial industrialization.

Manchuria is a good trophy

Torn away from China in late 1931 - early 1932 by Japanese troops, Manchuria was a very significant trophy for the Japanese. Its total population was 36 million people, including about 700 thousand Koreans and 450 thousand Japanese. From the moment when in 1906 Japan received the South Manchu Railway from Russia (Port Chanchun-Port Arthur) from Portsmouth Peace to Russia, relocation from Japan and Korea began to this part of Manchuria.

Manchuria annually produced about 19 million tons of grain crops, mined about 10 million tons of coal, 342 thousand tons of pig iron. A powerful railway was operating, the large port of Dairen, while the second most powerful port on the entire coast of China after Shanghai, with a capacity of about 7 million tons per year. Already in the early 1930s there were about 40 airfields, including in Mukden and Harbin, the airfields were with repair and assembly workshops.

In other words, by the time of the Japanese capture, Manchuria had a very well-developed economy, which had huge and almost untouched reserves of all kinds of minerals, free land, vast forests suitable for river construction. The Japanese took up the transformation of Manchuria into a large military-industrial base and were very successful in this.

A characteristic feature of Manchuria itself was that the command of the Kwantung Army that actually controlled it was categorically against attracting large Japanese concerns to its development, since the military did not like the capitalist element typical of the Japanese economy, which was difficult to control. Their slogan was: "Development of Manzhou-Guo without capitalists", based on centralized management and planned economy. Therefore, the Manchu economy at first was undoubtedly dominated by the South Manchu Railway (or Mantetsu) - a large concern that had exclusive rights and owned everything from railways and coal mines to hotels, opium trade and brothels.

However, for large-scale development capital was needed, and the Japanese militarists in Manchuria had to agree with a large Japanese concern Nissan, established in 1933 as a result of the merger of the DAT Jidosia Seizo automobile company with the Tobata metallurgical company. The founder of Yoshisuke Aikawa (also known as Gisuke Ayukawa) quickly found a common language with the Japanese military, began to produce trucks, planes and engines for them. In 1937, the concern moved to Manchuria and adopted the name “Manchurian Heavy Industry Development Company” (or “Mangyo”). Two companies, Mangyo and Mantetsu, divided the spheres of influence, and industrialization in Manchuria began.

First Five Year Plan

In 1937, the first five-year development plan was developed in Manchuria, which provided for an initial investment of 4,8 billion yen, then, after two revisions, plans increased to 6 billion yen, of which 5 billion yen went to heavy industry. Just like in the first five-year plan in the USSR.

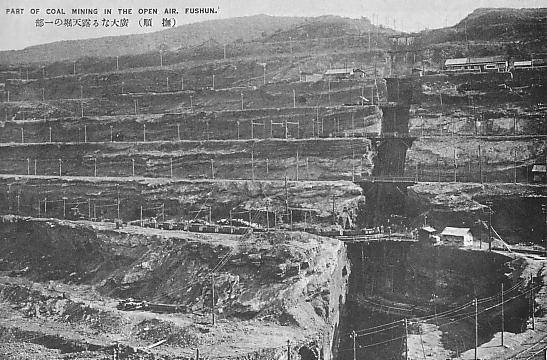

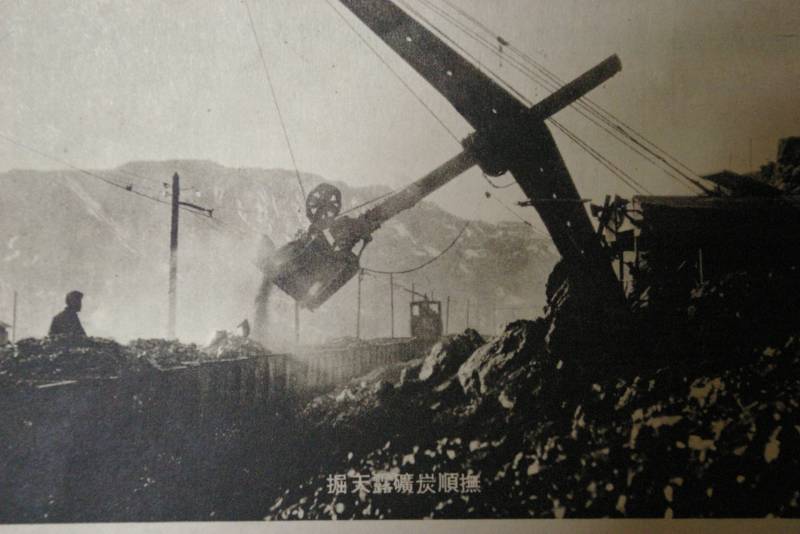

Coal. Manchuria had 374 coal-bearing districts, of which 40 were under development. The five-year plan provided for an increase in production to 27 million tons, then to 38 million tons, but it was not implemented, although production increased to 24,1 million tons. However, the Japanese tried to get the most valuable coal in the first place. The Fushun coal mines, created by the Russians during the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway and South Ural Railway, acquired the largest open-pit coal mine at that time producing high-quality coking coal. He was taken to Japan.

Coal was to become a raw material for the production of synthetic fuel. Four synthetic fuel plants were built with a total capacity of up to 500 thousand tons per year. In addition, there were reserves of oil shale in Fushun, for the development of which a plant was built. The plan provided for the production of 2,5 million tons of oil and 670 million liters (479 thousand tons) of gasoline.

Cast iron and steel. In Manchuria, a large Siova metallurgical plant was built in Anshan, which the Japanese regarded as an answer to the Kuznetsk Metallurgical Plant. He was well endowed with reserves of iron ore and coal. By the end of the first five-year plan, it had ten blast furnaces. In 1940, the plant produced 600 thousand tons of rolled steel per year.

In addition to it, the metallurgical plant in Bensihu was expanding, which was supposed to produce 1200 thousand tons of pig iron in 1943. It was an important plant. He smelted low sulfur cast iron, which went to Japan for the smelting of special steels.

Aluminum. To develop aircraft manufacturing in Manchuria, mining of shale containing alumina was started, and two aluminum plants were built - in Fushun and Jirin.

In Manchuria there was even its own DneproGES - the Shuyfinskaya hydroelectric station on the Yalu River, bordering between Korea and Manchuria. The dam, 540 meters long and 100 meters high, gave pressure to seven Siemens hydraulic units, 105 thousand kW each. The first unit was put into operation in August 1941 and provided current for supplying the large Siova metallurgical plant in Anshan. The Japanese also built the second large hydroelectric power station - Fynmanskaya on the Sungari River: 10 hydraulic units of 60 thousand kW each. The station was launched in March 1942 and gave current to Xinjin (now Changchun).

“Mangyo” was the core of industrialization, it included: “Manchurian coal company”, metallurgical plants “Siova” and Bensihu, production of light metals, mining and production of non-ferrous metals, as well as automobile factory “Dova”, “Manchu joint-stock company of heavy engineering ”, An industrial engineering company, an aircraft manufacturing company, and so on. In other words, the Japanese equivalent of the People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry.

In July 1942, a meeting was held in Xinjing that summed up the results of the first five-year plan. In general, the plan was implemented at 80%, but for a number of points there was a good effect. Iron smelting increased by 219%, steel by 159%, rolled products by 264%, coal mining by 178%, copper smelting by 517%, zinc by 397%, lead by 1223%, aluminum by 1666% . The commander of the Kwantung Army, General Umezu Yoshijiro, could exclaim: “We did not have heavy industry, we have it now!”

Weapon

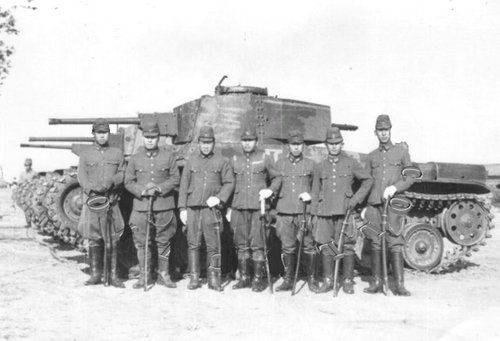

Manchuria acquired large industrial capacities and now could produce a lot of weapons. There is not much data about this since the Japanese, with the outbreak of war, classified them and published almost nothing. But something is known about this.

According to some sources, the aircraft factory in Mukden could produce up to 650 bombers and up to 2500 engines per year.

Dova automobile plant in Mukden could produce 15-20 thousand trucks and cars a year. In Andun in 1942, the second car factory, an assembly plant, also opened. There was also a rubber products factory in Mukden that produced 120 thousand tires every year.

Two steam locomotive plants in Dairen, another steam locomotive factory in Mukden and a carriage factory in Mudanjiang - with a total capacity of 300 steam locomotives and 7000 wagons per year. For comparison: in 1933, South Ural Railway had 505 steam locomotives and 8,1 thousand freight cars.

In Mukden, among other things, the Mukden arsenal emerged - a conglomerate of 30 manufactures that produced rifles and machine guns, assembled tanks, and produced ammunition and artillery. In 1941, the Manchurian Powder Company appeared with six factories in the main industrial centers of Manchuria.

Second Five Year Plan

Very little is known about him, and only from the works of American researchers who studied documents and materials captured in Japan. In Russia, in principle, there should be trophy documents from Manchuria, but so far they have not been completely investigated.

The second five-year plan in Manchuria was not a separate plan, like the first, but was developed in close integration with the needs of Japan and was, in fact, part of the general plans for military-economic development of Japan, including all occupied territories.

In it, greater emphasis was placed on the development of agriculture, the production of crops, especially rice and wheat, as well as soybeans, and on the development of light industry. This circumstance, just as in the second five-year plan in the USSR, was due to the fact that the industrial swing should nevertheless be based on the proportional development of agriculture, which provides food and raw materials. In addition, Japan was more in need of food.

The details of the second five-year plan and the development of Manchuria in 1942-1945 still require research. But for now, you can point out a couple of strange circumstances.

Firstly, a strange and yet inexplicable decline in production in 1944 compared with 1943. In 1943, iron smelting amounted to 1,7 million tons, in 1944 - 1,1 million tons. Steel smelting: 1943 - 1,3 million tons, in 1944 - 0,72 million tons. At the same time, coal mining remained at the same level: 1943 - 25,3 million tons, 1944 - 25,6 million tons. What happened in Manchuria that steel production declined by almost half? Manchuria was far from the theaters of operations, it was not bombed, and this cannot be explained by purely military reasons.

Secondly, there is interesting evidence that the Japanese for some reason created huge steel production capacities in Manchuria. In 1943 - 8,4 million tons, and in 1944 - 12,7 million tons. This is strange, since steelmaking capacities and rolled metal production capacities are usually balanced. The capacities were loaded by 31% and 32%, respectively, which yields rolled products in 1943 of 2,7 million tons, and in 1944 - 6 million tons.

If this is just not the mistake of the American researcher R. Myers from the University of Washington, who published these data, then this is an extremely interesting military-economic fact. In 1944, Japan produced 5,9 million tons of steel. If in addition to this there was still production of 6 million tons of rolled metal, then Japan in total had very significant resources for steel, and, consequently, for the production of weapons and ammunition. If this is true, then Japan should have received from somewhere outside a significant amount of steel suitable for processing into rolled products, most likely from China. This point is still unclear, but it is very intriguing.

In general, in the military-economic history of the Second World War there is still something to explore, and the military economy of the Japanese Empire and the occupied territories here comes first.

Information