Crimea in 1918-1919. Intervents, local authorities and whites

Politics of the Second Crimean Government

The government of Solomon of Crimea relied on Denikin’s army. The Crimean peninsula entered the scope of the Volunteer Army in agreement with the government of S. Crimea, was busy with small white units, began to recruit volunteers. At the same time, Denikin announced non-interference in the internal affairs of the Crimea.

The government of S. Crimea believed that it was a model of the “future All-Russian power”. The cabinet’s leading politicians were Minister of Justice Nabokov and Minister of Foreign Affairs Vinaver, who were among the leaders of the All-Russian Constitutional Democratic Party (Cadets). The Crimean government tried to cooperate with all organizations and movements that sought to "reunite United Russia", saw allies in the Entente, intended to re-establish public self-government bodies and wage a determined struggle against Bolshevism. Therefore, the regional government did not interfere in the repressive policies of the whites (“white terror”) in relation to representatives of the opposition socialist and trade union movement.

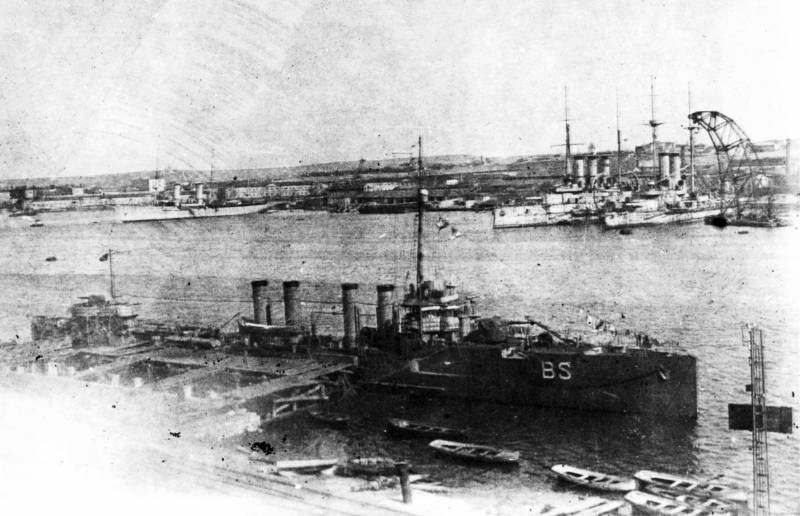

26 November 1918, the Entente squadron (22 pennant) arrived in Sevastopol. The Crimean regional government as a whole expressed its respect to the invaders. November 30 Western occupiers occupied Yalta. The Crimean government attached great importance to the presence of the Entente forces. Therefore, the Ministry of External Relations headed by Vinaver moved to Sevastopol, which became the main stronghold of the interventionists. At this time, the Entente, having won the World War, enjoyed great popularity among the Crimean public and intellectuals. The Cadets and the representatives of the White movement believed that under the cover of such a force they would be able to form a powerful army that would launch an offensive against Moscow. It is possible that divisions of the Entente will take part in this attack. The Bolsheviks, as Crimean politicians believed, were already demoralized and quickly defeated. After that, it will be possible to form a "All-Russian power."

However, the white Crimean-Azov army of General Borovsky did not become a full-fledged unit. Her number did not exceed 5 thousand fighters. The chain of small white detachments stretched from the lower Dnieper to Mariupol. In Crimea, they were able to create only one full-fledged regiment of volunteers - 1-th Simferopol, the other parts remained in their infancy. There were fewer officers in the Crimea than in Ukraine, and we drove here to sit out and not fight. The locals, like the fugitives from the central regions of Russia, also did not want to fight. They hoped to protect foreigners - first the Germans, then the British and French. General Borovsky himself showed no great managerial qualities. He rushed about between Simferopol and Melitopol, not really doing anything (plus he turned out to be a drunkard). The attempt to mobilize in Crimea also failed.

Deterioration of the situation on the peninsula

Meanwhile, the economic situation on the peninsula gradually deteriorated. Crimea could not exist in isolation from the general economy of Russia, many ties were broken due to the Civil War and the conflict with Kiev. Enterprises shut down, unemployment grew, finance sang romances. There were various monetary units in the peninsula: “Romanovka”, “Kerenki”, Don paper money (“bells”), Ukrainian rubles, German marks, French francs, British pounds, American dollars, coupons from various interest-bearing papers, loans, lottery tickets, etc. The sharp deterioration in living conditions led to an increase in revolutionary sentiment and the popularity of the Bolsheviks. This was facilitated by the Soviet government, sending its agitators to the peninsula and organizing partisan detachments.

By the end of 1918 - the beginning of 1919 of the year, there were red underground fighters in almost all Crimean cities. Guerrillas acted throughout the peninsula. In January, the Reds 1919 rebelled in Evpatoria, they were able to suppress it only with the help of the battalion of the Simferopol regiment and other White divisions. The remains of the red ones, headed by Commissioner Petrichenko, sat down in the quarries, regularly making forays from there. After several fights, White was able to knock out the Reds and from there, many were shot. Under the control of the Communists were trade unions, which almost openly led Bolshevik agitation. The trade unions responded with rallies, strikes and protests against government actions to tighten policies. The peninsula was full weaponstherefore, not only the red rebels acted in the Crimea, but also the "green" ones - gangsters. The criminal revolution that began in Russia with the beginning of the unrest, swept the Crimea. The usual thing was shooting in the streets.

The volunteers responded by intensifying the “white terror” to the activation of the red and green ones. Formed units of whites were forced not to go to the front, but to engage in the protection of order, to carry out punitive functions. This did not contribute to the growing popularity of the White Army among the local population. White terror pushed many Crimeans from the Volunteer Army.

Thus, there was no real power behind the government of S. Crimea. It existed only under the protection of whites and invaders. Gradually, the first rainbow dreams of the Crimean politicians began to shatter about the harsh reality. It was not possible to form a powerful white Crimean army. White Crimeans did not want to go and defend the “united and indivisible Russia”.

Interventionist policy

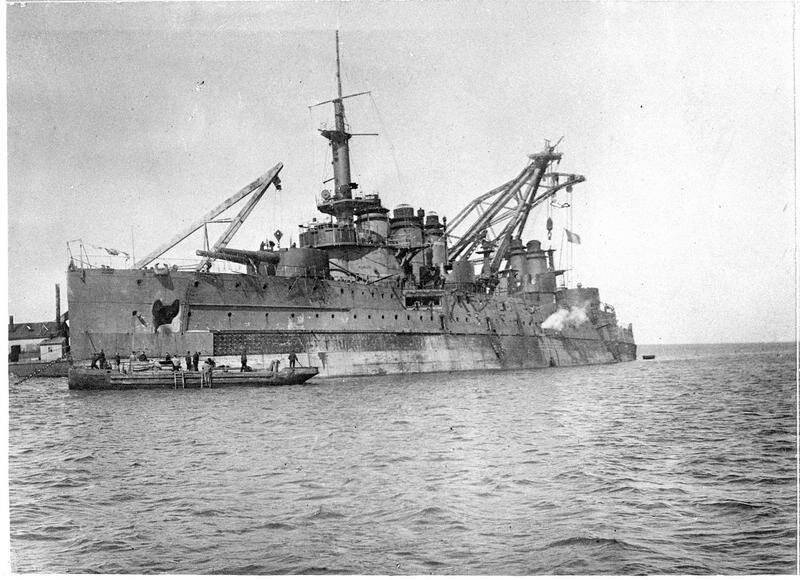

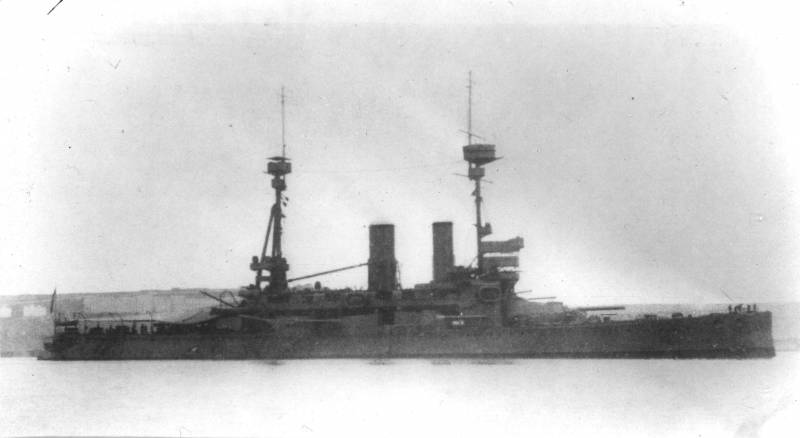

The interventionists (mainly the French and Greeks), with the main base in Sevastopol (the powerful fleet of Admiral Amet and more than 20 thousand bayonets), took a peculiar position. The garrison was only in Sevastopol, the French were interested in control of this naval fortress. The interventionists captured several ships of the former fleet Russia, as well as part of the stock of coastal weapons.

Denikin suggested that the "allies" take at least small garrisons Sivash, Perekop, Dzhankoy, Simferopol, Feodosiya and Kerch, to ensure order there, to protect the entrance to the peninsula, about freeing the white parts for action at the front. However, the Allied Command refused to do so. The interventionists in Sevastopol (as well as throughout Russia) avoided direct battles with the Reds, preferring to set off the Russians with the Russians for general exhaustion, the exsanguination of the Russian civilization and the Russian people. At the same time, their troops quickly decomposed and could no longer fight. Moreover, there was a threat of transferring revolutionary sentiments to the Western countries themselves. The sailors of the French fleet took part in demonstrations with red flags. Lenin and his slogans were very popular among the working masses of Western Europe at that time, and the campaign “hands off Soviet Russia!” Was very effective.

On the other hand, the Westerners believed that they were the masters of the Crimea and the Volunteer Army was in their submission. Therefore, the Allied command actively intervened in the activities of the Crimean government and hindered the activities of Denikin. The invaders interfered with the launch of the “white terror” in Sevastopol, where they organized “democracy” and where the Bolsheviks and the red trade unions felt good.

When the Commander-in-Chief of the All-Union People's Defense Council Denikin decided to transfer the Headquarters from Ekaterinodar to Sevastopol, the interventionists forbade him to do so. And the government of S. Crimea tried in every way to curry favor with the Allies, so that the Westerners would protect the peninsula from the Red Army. The Crimean government, which existed only because of the presence of Denikin’s army in the south of Russia, put sticks into the wheels of Denikin. With the filing of the government in the Crimean press, a campaign was launched against the Volunteer Army, which was considered "reactionary," "monarchical," not respecting the autonomy of Crimea. On the issue of mobilization on the peninsula, the government of S. Crimea under the pressure of General Borovsky, now the interventionists, then the trade unions behaved inconsistently. Either she announced the beginning of the mobilization, then she abolished it, then she called the officers, then she called the officer mobilization optional, voluntary.

The onset of the Reds and the fall of the Second Crimean Government

By the spring of 1919, the external situation had deteriorated sharply. In the Crimea, it was possible more or less to restore order. However, in the north, the Reds came to Yekaterinoslav, headed by Dybenko. They connected with the forces of Makhno. The Russian 8 corps of General Schilling (there were only 1600 fighters in it), which was formed there, retreated to the Crimea. As a result, regular Soviet units and Makhno detachments came out against small volunteers, which quickly grew in size and adopted a more correct organization. Fights began in the area of Melitopol. Denikin wanted to transfer Timanovsky's brigade from Odessa to this site, but the Allied command did not give permission.

In March, the 1919 of the year, the Allies unexpectedly for the white command surrendered Kherson and Nikolaev in red. The Reds had the opportunity to attack the Crimea from the western direction. Under the influence of the success of the Red Army in the Ukraine and Novorossia, the insurgent movement in the Crimea was revived, and both the red insurgents and ordinary bandits acted. They attacked the communications of whites, trashed carts. Crimean trade unions demanded the removal of the White Army from the peninsula and the restoration of Soviet power. The railroad workers were on strike, refusing to transport the cargo of Denikin’s army.

White could not hold the front in Tavria with extremely weak forces. It was decided to withdraw the troops to the Crimea. Began the evacuation of Melitopol. However, it was difficult to retreat. From the north and west, the Reds advanced with large forces, trying to cut off the whites from Perekop. The main part of the white troops retreated to the east, on the connection with the Donetsk group of the Volunteer Army. The Combined Guards regiment was defeated, where the battalions were called the old Guards regiments (Preobrazhensky, Semenovsky, etc.). With battles from Melitopol to Genichesk only the battalion of the Simferopol regiment and other small forces of General Schilling retreated. The second battalion of the Simferopol regiment took positions at Perekop.

In fact, there was no defense of the Crimea. Neither the S. Crimea government, nor the interventionists, nor the whites prepared to defend the Crimean peninsula. Given the power of the Entente, such a scenario was not even considered. Franche d'Espere, appointed in March by the High Commissioner of France in southern Russia and replacing Bertello in this post, promised Borovsky that the Allies would not leave Sevastopol, that Greek troops would soon be landed here to secure the rear, and White should advance to the front.

At the end of March, Schilling, abandoning the armored train and guns, retreated from the Chongar peninsula to Perekop. White gathered all the forces at Perekop: the Simferopol regiment, various units that had begun to form, 25 guns. The Allied Command sent only a company of Greeks. For three days the Reds fired at enemy positions and April 3 went on the attack, but was beaten off. However, at the same time with the frontal attack, the Red Army men crossed the Sivash and began to go to the rear to the white. This idea was proposed by Dybenko, the father of Makhno. White retreated and tried to hold on to Ishun positions. The commander of the allied forces, Colonel Thrusson promised help with troops and resources. However, white rare chains were easily broken by red. A detachment of decisive Colonel Slaschova organized the broken parts and went to the counter. The White Guards rejected the Reds, went to Armenian. But the forces were unequal, the whites quickly exhausted, and there were no reinforcements. In addition, the Red Command, taking full advantage of the forces, organized a landing of troops on the Chongar Strait and on the Arabat Spit. Under the threat of complete encirclement and destruction of the white troops at Perekop, they retreated to Dzhankoy and Theodosia. The Crimean government fled to Sevastopol.

Meanwhile, Paris gave the order to withdraw allied forces from Russia. 4-7 April, the French fled from Odessa, leaving the whites remaining there. On April 5, the Allies concluded a truce with the Bolsheviks in order to calmly evacuate Sevastopol. They evacuated to 15 April. The French battleship Mirabeau was stranded, so the evacuation was delayed to release the ship. Trusson and Admiral Amet suggested to the commandant of the Sevastopol fortress General Subbotin and the commander of the Russian ships Admiral Sablin that all the institutions of the Volunteer Army should immediately leave the city. At the same time, the allies during the evacuation robbed the Crimea, removing the valuables of the Crimean government transferred to them for “storage”. On April 16, the last ships departed, taking white and refugees to Novorossiysk. Prime Minister S. Crimea fled along with the French. Many Russian refugees and their allies reached Constantinople and then on to Europe, forming the first Odessa-Sevastopol wave of emigration.

By 1 May 1919, the Reds liberated Crimea. The remaining white forces (about 4 thousand people) retreated to the Kerch Peninsula, where they entrenched on the Ak-Monaysky isthmus. Here whites were supported by Russian and British ships with fire. As a result, the 3 Army Corps, into which the Crimean-Azov Army was transformed, remained in the east of the peninsula. The Reds themselves did not show much stubbornness here and stopped the attacks. It was believed that soon Denikin’s army would be defeated and whites in the Kerch area would be doomed. Therefore, the Red troops confined to blockade. The main forces of the Red Army were redeployed from the Crimea to other areas.

Crimean Soviet Socialist Republic

The 3-I Crimean Regional Conference of the RCP (B), which was held in Simferopol on 2 8-29 on April 1919, adopted a resolution on the formation of the Crimean Soviet Socialist Republic. 5 May 1919 was formed by the Provisional Workers 'and Peasants' Government of the KSSR headed by Dmitry Ulyanov (Lenin's younger brother). Dybenko became People's Commissar of military and maritime affairs. The Crimean Soviet Army was formed from units of the 3 of the Ukrainian Soviet division and local formations (they managed to form only one division — more than 9 thousand bayonets and sabers).

6 May 1919 published a Government Declaration, which reported the republic’s tasks: the creation of a regular Crimean Soviet army, the organization of local council authority and the preparation of a congress of Soviets. The KSSR was declared not a national, but a territorial entity, it was declared about the nationalization of industry and the confiscation of landowner, kulak and church lands. Banks, financial institutions, resorts, railway and water transport, fleet, etc. were also nationalized. Evaluating the period of the “second Crimean Bolshevism,” a contemporary and witness to the events Prince V. Obolensky noted the relatively “bloodless” character of the established regime. This time there was no mass terror.

The Soviet power in Crimea did not last long. Denikin's army in May 1919 began its offensive. 12 June 1919, a white landing of General Sashchev landed on the peninsula. By the end of June, the White Army captured the Crimea.

- Alexander Samsonov

- Smoot. 1919 year

How the British created the Armed Forces of the South of Russia

How to restore Soviet power in Ukraine

How Petliurists led Little Russia to a complete catastrophe

How defeated Petliurism

Give the boundaries of 1772 of the year!

Battle for the North Caucasus. How to suppress the Terek Uprising

Battle for the North Caucasus. CH 2. December battle

Battle for the North Caucasus. CH 3. The January accident of the 11 Army

Battle for the North Caucasus. CH 4. How the 11 army died

Battle for the North Caucasus. CH 5. Capture of Kizlyar and the Terrible

Battle for the North Caucasus. CH 6. Furious assault of Vladikavkaz

How Georgia tried to seize Sochi

How the Whites crushed the Georgian invaders

The war of February and October as a confrontation between two civilization projects

How did the "Flight to the Volga"

How Kolchak's army broke through to the Volga

Catastrophe of the Don Cossacks

Verkhniyon uprising

How "Great Finland" planned to seize Petrograd

"All to fight with Kolchak!"

Frunze. Red Napoleon

The missed opportunities of the army of Kolchak

May offensive of the Northern Corps

How white broke through to Petrograd

Battle for the South of Russia

Strategic change on the southern front. Manych operation

Crimea on fire Russian distemper

Information