Electronic warfare. "War of the Magi". Ending

The second story related to civilian radio networks happened to the Parisian radio, which the British often listened to through household radios. Light music and variety shows, broadcast by the French from the occupied country, brightened up the everyday life of many English. Of course, given the fact that it was necessary to pass by the ears abundant fascist propaganda. The British began to notice that at some time intervals the level of signal reception from Paris increased sharply, which forced to muffle the sound in the receivers. Moreover, this preceded the Luftwaffe night raids on certain cities. In a strange coincidence, experts from the Ministry of Defense sorted out: they revealed a new German bomber radar guidance system aviation.

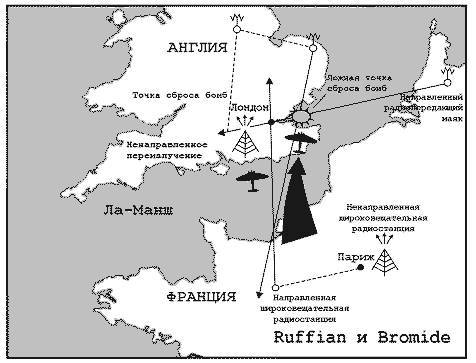

Before the departure of the aircraft from the airfields of France, the Paris radio station switched from broadcasting to broadcasting mode with simultaneous guidance of a radar repeater to a British city of sacrifice. Residents of this city just fixed a noticeable increase in French music on the air. Meanwhile, the squadrons of the bombers approached them, orienting themselves in space along a narrow beam from the radar guide. The second beam, as usual, crossed the main "radio" at the point of dropping bombs, that is, over the night city of England. The crews of the Luftwaffe, just listening to the entertainment programs of the French, quietly traveled to London or Liverpool. The British called the system the name Ruffian and have been looking for an antidote for it. It is noteworthy that it is still not completely clear how the Germans managed to form a narrow (up to 3 degrees) and very powerful electromagnetic beam at the level of 40's technology development. The British responded mirror - they created a broadcast repeater of Paris radio on their own territory, which completely confused Hitler's navigators. German bombs began to fall anywhere, and this was a definite victory for the British electronics engineers. This system went down in history under the name Bromide.

The interaction scheme of the German Ruffian and the British Bromide

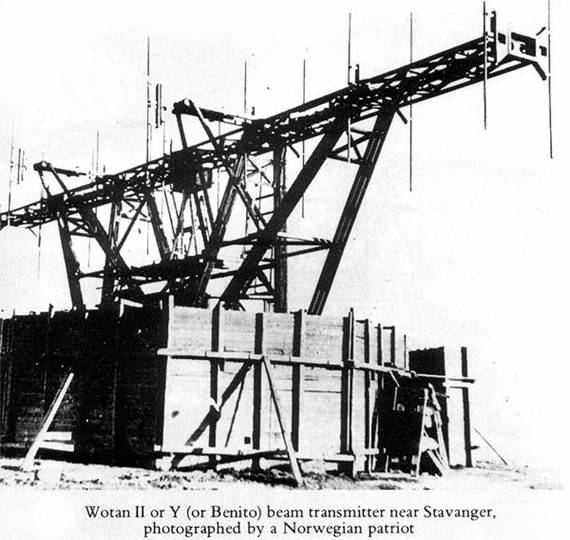

Benito radar complex

By the beginning of 1941, the Germans made a reciprocal move, creating the Benito complex dedicated to the leader of the Italian fascists - Duce. In this case, it was necessary to organize a transfer of German agents to the territory of England, equipped with portable radio transmitters. With their help, the pilots of the bombers received a full amount of information about the goals of the strikes and their own location. Navigation support was also provided by the German Wotan radar stationed in the territories occupied by Germany. The response program of the Domino British intelligence service was already similar to the classic spy radio game - groups of operators in excellent German language misled the pilots of the Luftwaffe, who again dropped bombs in the open field. A few Domino bombers were generally able to land on British airfields in complete darkness. But there was a tragic page in the history of electronic warfare against the Germans: Domino operators mistakenly sent German planes to bomb Dublin from 30 to 31 in May 1941. Ireland at that moment remained neutral in world war.

An "erroneous" raid on the Irish capital of the Luftwaffe was made on the night of May 31. The northern districts of Dublin, including the presidential palace, were bombed. Killed 34 man.

Similar to the act of despair of the Luftwaffe was the forced illumination of targets for night bombing strikes with illuminating ammunition. In each strike group, several aircraft were set up for these purposes, responding to the coverage of British cities before the bombing. However, the settlements still had to be reached in complete darkness, so the British simply began to make giant conflagrations at a distance from large cities. The Germans recognized them as the lights of a big city and bombarded hundreds of tons of bombs. By the end of the active phase of the air confrontation in the skies of England, both sides suffered significant losses - the British 1500 fighters, and the Germans about 1700 bombers. The emphasis of the Third Reich shifted east, and the British Isles remained unchained. In many ways, it was the electronic opposition of the British that caused only one fourth of the bombs dropped by the Germans to achieve their goals - the rest fell on wastelands and forests, or even in the sea.

A separate page in the history of EW between Britain and Hitler’s Germany was the confrontation with air defense radars. The Germans, in order to combat the Chain Home system's radars mentioned earlier, deployed the Garmisch-Partenkirchen false pulse equipment on the French coast of the English Channel. Working in the radio range 4-12 meters, this technique created false group air targets on the screens of English locators. Such jamming stations were re-equipped for installation on airplanes - in 1942, several Heinkel He 111s were immediately equipped with five transmitters, and they successfully “littered” the air in the English air defense zone. Chain Home was a certain bone in the throat of the Luftwaffe, and in an attempt to destroy them, the Germans built radiation detectors of locators on several Messerschmitt Bf 110. This made it possible at night to orient the bombers to strike at the English radar, but a powerful aerostat cover prevented the implementation of such an idea. Electronic warfare was not limited to the English Channel surroundings - in Sicily, the Germans in 1942 installed several Karl-type noise interference stations, which they attempted to prevent British air defense locators and radar-guidance equipment for Malta. But the power of Karl was not always enough to work on remote targets, so their effectiveness left much to be desired. Karuso and Starnberg were quite compact stations of electronic suppression, which allowed them to be installed on bombers to counteract fighter pointing channels. And since the end of 1944, four Stordorf complexes have been commissioned, including a network of new stations jamming communication channels of the allied forces called Karl II.

Over time, the Germans, together with the Japanese, came to a very simple method of dealing with radar - the use of dipole reflectors in the form of strips of foil, which illuminated the screens of the locators of Allied forces. The first were the Japanese Air Force, when in May 1943 of the year threw such reflectors during raids on US forces on Guadalcanal. The Germans called their “foil” Duppel and used it since the fall of 1943. The British began to throw metallized paper Window during the bombing of Germany a few months earlier.

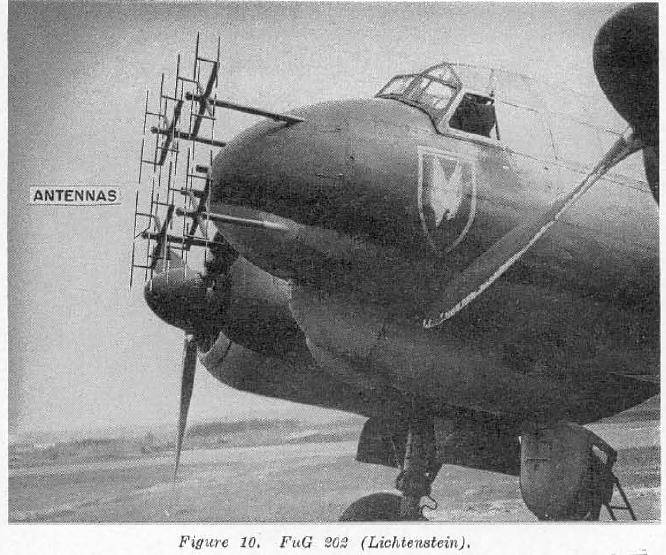

Equally important for the German Air Force was the suppression of the radar systems of British night bombers, which inflicted sensitive strikes on the infrastructure of the Reich. For this purpose, German night fighters were equipped with Lichtenstein radar under the symbol C-1, later SN-2 and B / C. Lichtenstein was quite effective in defending the night sky of Germany, and the British Air Force for a long time could not detect the parameters of its work. It was a matter of the short range of work of the German airborne radar station, which caused the radio intelligence aircraft to converge with the German fighters.

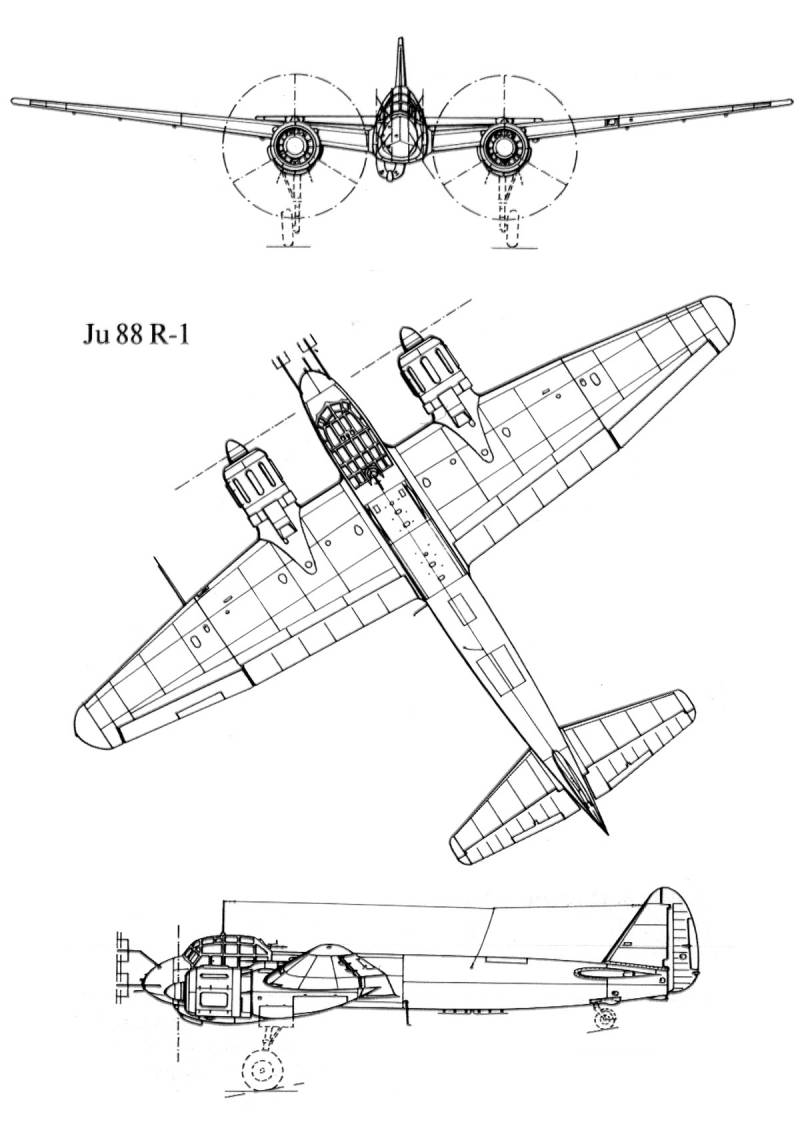

Lichtenstein antennas on a Junkers Ju 88 aircraft

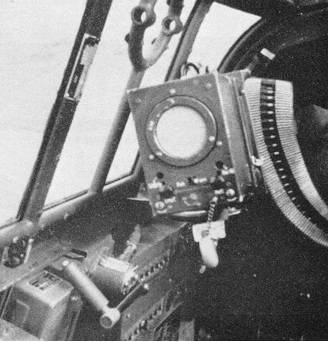

Remote control radar Lichtenstein SN-2

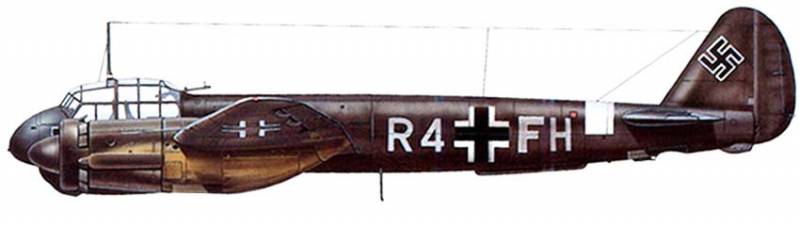

Ju 88R-1

Often it ended tragically, but 9 in May 1943 of the year in Britain boarded a Ju 88R-1 with a deserted crew and a copy of Lichtenstein on board. Based on a study of radar stations in England, an Airborne Grocer aircraft jammer station was created. It was interesting to confront German special means of Monica onboard radar (frequency 300 MHz) installed in the rear hemisphere of the British bombers. It was designed to protect aircraft in the night sky of Germany from attacks from behind, but perfectly unmasked the aircraft carrier. Especially for Monica, the Germans developed and installed the Flensburg detector on night fighters at the start of the 1944 of the year.

Flensburg Detector Antennas at Wings Ends

Such games continued until July 13 1944, until the British landed at night on their own airfield (not without the help of the tricks mentioned in the article) Ju 88G-1. The car was full of mince - and Lichtenstein SN-2, and Flensburg. From that day on, Monica was no longer installed on the British Bomber Command vehicles.

British radar H2S, known in Hitler's Germany as Rotterdam Gerät

A real engineering masterpiece of the British has become the H2S radar of the centimeter range, which allows detecting large contrast targets on the ground. Developed on the basis of a magnetron, H2S was used by British bombers both for navigation and for targeting bombing. From the beginning of 1943, the technology went into a large wave to the troops - the radar was placed on Short Stirling, Handley Page Halifax, Lancaster and Fishpond. And already February 2 shot down over Rotterdam Stirling presented the Germans H2S in a fairly tolerable state, and on March 1 presented this gift to Halifax. The Germans were so impressed with the level of technical development of the radar station that they gave it the semi-mystic name Rotterdam Gerät.

Radar control unit Naxos in the cockpit Bf-110

The fruit of studying such a device was the Naxos detector, operating in the 8-12-centimeter range. Naxos became the ancestor of a whole family of receivers installed on airplanes, ships, and EW ground stations. And so on - the British switched back to the 3-centimeter wave (H2X), and in the summer of 1944 the Germans created the corresponding Mucke detector. A little later, the war ended and everyone sighed with relief. Not for long ...

Based on:

Mario de Arcangel. Electronic warfare From Tsushima to Lebanon and the Falkland Islands. 1985.

Kolesov N. A., Nasenkov I. G. Radio electronic warfare. From past experiments to the decisive front of the future. 2015.

Electronic warfare. "War of the Magi". Part of 1.

Information