Shipyard named after 61 communard. Rear Admiral Butakov against business people

Rumors that a joint-stock company of shipping and trade, created with the support of the highest level, required experienced seamen, agitated the storekeepers - veterans of the defense of Sevastopol. The office of Rear Admiral Butakova was simply overwhelmed with a mass of various requests for transfer to a new duty station, applications for pensions, housing and material assistance.

In the conditions of the perturbation of the fleet economy, the reduction and displacement of a large number of people, materials and property by tropical vegetation, the everlasting embezzlement and bribery has rapidly developed. Butakov was a stubborn man by nature and tried to fight this old and tenacious hydra living in the bowels of the state apparatus.

Elusive quartermasters

Many did not like Grigory Ivanovich Butakov at the new service station in Nikolaev, considering him an upstart. His relations with Rear Admiral Alexander Ignatievich Shwendner, who was the deputy for the quartermaster, were particularly tense. By the time Butakov arrived at the Black Sea Fleet after the end of the cadet corps, Schwendner had already commanded the Kolkhida steamer and was considered a very experienced sailor. Now, the youngest in age, but Grigory Ivanovich, who is ahead of his post, was the head of Schwendner, which, most likely, the latter did not like very much.

But the conflict, which gave rise to rather noisy and foul-smelling consequences, broke out between the two admirals not at all because of the career steps. Butakov, being an honest and responsible man, having arrived in Nikolaev, found himself in a kind of cat role in a grain warehouse. Local "mice" have long since distributed among themselves the "mountains of grain", the paths between them, the sequence and number of "feeding." The “cat” who arrived in these schemes did not fit at all and frankly interfered. While the "mice" warped under the floor, their existence was an inevitable evil, for the quartermaster ranks are subject to temptation at all times. But when the plunderers began to become impudent, Butakov had to take unpopular measures.

Grigory Ivanovich was informed that his deputy for the quartermaster, Rear Admiral Shvendner, was involved in food speculation. More specific data indicated the delivery of thousands of quarters of rotten flour to the 13 marine agency. A certain effective owner, Mr. Kireevsky, started a dubious habit of systematically improving his financial situation at the expense of the fleet. So, for example, this merchant capable of commercial and other matters was taken from the shipyard 16 thousands of tons of sheet iron in exchange for the supply of flour. Moreover, if the iron was still in the public warehouse, it was quite tangible and man-made, then the fact of the existence of 13 thousands of quarters of flour, suitable for food, raised doubts.

A sudden test carried out by Butakov revealed that the specified flour could be quite confidently applied, but only as a biological weapons. If this regrettable fact with respect to Mr. Kireyevsky were sporadic, and his behavior could have been attributed to the costs of a passion for the free spirit of commerce, the scandal would not have overflowed the shores. However, in fact, Kireevsky was a confidant, accomplice and accomplice of the esteemed Rear-Admiral Schwendner and was only a part of a well-established system.

For example, another no less energetic merchant named Bortnik, taking the forest wood at a bargaining price, also sent low-quality supplies under the obligation. The scheme, which was well developed and adjusted, allowed fleets to be sold to private individuals and received completely inedible food in return. The difference in price, of course, settled in the pockets of a business financial group led by Rear Admiral Schwendner.

Since the end of the Crimean War, large warehouses with naval and army property have been located in the southern regions. After the signing of the world, this property began to disappear somewhere. So, one of the schemes for extracting quick money was the sale of the Nicholas Admiralty ship forest through nominees to Baltic shipyards.

The measures taken by Butakov were the most decisive. A special commission was set up to investigate the incident. Having found in the documents numerous violations, members of the commission expressed their views. Negotsiant Kireevsky, an expert on quality food, was taken into custody, and his warehouses sealed, Rear Admiral Shwendner - suspended from business during the investigation.

Clearly hearing the angry squeak caught on the hot "mice", Grigory Ivanovich immediately notified Petersburg about the events. Grand Duke Constantine, who was on good terms with Butakov and even, to some extent, patron of him, reported on the incident to Alexander II. The case was given a full-fledged move, and the “highest established commission” headed by Prince Dmitry Alexandrovich Obolensky, the confidant of Grand Duke Constantine, who was admiral general at that time, went to Nikolaev urgently.

While Mr. Obolensky was traveling from St. Petersburg to Nikolaev, the commission created on the spot by Butakov did not waste any time trying to poison the savory stories in the smoking lounge. By virtue of the numerous violations found in the affairs of the Black Sea intendancy, Rear Admiral Shwendner, seven staff officers, four officials and two businessmen, Kireyevsky and Bortnik, were committed to the military court.

The special color of the scandal gave the fact that both merchants were, in between cases, honorary citizens of the city of Nikolaev. The sentence was quite strict: Schwendner was expelled from service, some of the officers, deprived of their ranks and orders, were demoted to sailors. All losses incurred by the maritime department as a result of embezzlement and the supply of substandard materials were reimbursed from the property of convicts. The ruin and the reputation of the sinking to the bottom already hovered over the heads of “honorary citizens”, when events suddenly lay down on a new tack.

In the midst of a successful special operation for clearing the maritime department from businessmen in epaulets, the Obolensky commission arrived in Nikolaev and immediately showed the provincial fighters for clean hands and the fullness of state-owned warehouses a capital master class.

Prince Dmitry Alexandrovich Obolensky, being the director of the Commissariat Department, considered himself a sincere and enthusiastic fighter with various abuses. Like many metropolitan officials close to the highest echelons, Obolensky combined surprisingly balanced firepower and excellent maneuverability. Arriving in Nikolaev, he first praised Butakov for zeal, while angrily condemning criminals and embezzlers, but the course of the investigation, to use naval terms, made a turnaround.

The composition of the commission created by Grigory Ivanovich was significantly changed. As experts on the analysis of the incident with poor quality food, recently invited in the center of the hurricane Kireevsky, Bortnik and other people with not entirely clean hands were invited. Attempts by Butakov to exert some kind of influence on the rapidly changing circumstances, which acquired a completely different meaning and logic, came up against a polite but decisive rebuff of Prince Obolensky.

He began to conduct heart-to-heart talks with Grigory Ivanovich, during which, with the trusting tone of a person initiated into dense secrets, he strongly advised the rear admiral "... to leave the investigation already carried out completely away." In other words, the capital fighter with bribe-takers and embezzlers explicitly made it clear that one should not dig too deep. The members of the commission created by Butakov were pressured to force them to withdraw their conclusions back.

Infuriated, Grigory Ivanovich wrote a detailed report to Admiral General Grand Prince Konstantin asking for assistance. And then the “main caliber” came into play. “Not to interfere, but to render any assistance to the work of the commission,” rumbled out from under the spitz. The General-Admiral, of course, treated Butakov well, but the trouble is that Prince Obolensky’s piercing look of the bureaucratic apparatus looked at the much more serious figures caught on the hot Schwendner and the company.

The backstage whisper carefully called the name of Admiral Nikolai Fedorovich Metlin, the chief quartermaster, and then the manager of the maritime ministry. Most likely, Dmitriy Aleksandrovich as a dedicated person, delicate and generally legal, knew a lot in advance and therefore was sent to Nikolaev to fix the case, which was spoiled by the hot outdated Butakov. Obolensky took, and corrected.

As a result of “rechecking the check,” it turned out that Rear Admiral Shwendner and his subordinates suffered almost in vain because of the insatiable zeal of Rear Admiral Butakov. With these undoubtedly worthy people (of course, one should not forget about the most honest merchants Kireevsky and Bortnik), they were overly harsh and even unjustifiably cruel. The case of quartermaster thefts began to be undermined, passions, like a sail to calm, began to fall. As a result, the previous court decision against Schwendner and his colleagues was canceled.

Rear Admiral Butakov did not surrender. Hoping for the understanding of the Grand Duke Constantine, he sends a letter for a letter. The General-Admiral, who earlier emphasized his support and favor to Grigory Ivanovich, was now dry and strictly strict. From Petersburg reproachfully threatened with a finger: you there do not dig in the ground! What is curious, at first Konstantin verbally fully endorsed the desire of Grigory Ivanovich, if not to completely obliterate embezzlement, then at least to minimize it. When it turned out that the Rear Admiral lifted the veil too harshly and widely, hiding a measured mouse-scuffle from other people's eyes, the Grand Duke, fearing publicity and the inevitable scandal, began to trim the rigging of Butakov too active.

As a result, he, clearly realizing that the battle with the warehouse hydra, which turned out to be too many-headed, was lost, wrote a resignation report in their hearts. Konstantin shook the grand duke's finger, but did not accept the resignation. Specialists in the steamboat case in Russia at that time were all before, and Butakov was one of the leaders. When the Russian Shipping and Trade Society was established in 1856, the Grand Duke, who was one of its largest shareholders, found in Grigorii Ivanovich an assistant who had fully contributed to the development of the company.

So, among other things, at the end of 1856, Butakov was engaged in accepting steamboats purchased in England. In the same period began the first friction with Petersburg. The Rear Admiral believed that as the commander of the naval forces on the Black Sea (since the autumn of 1855, the Black Sea Fleet received a more modest name for the time and composition of the Black Sea Flotilla), ROPiT ships had to obey. However, the chairman of the society, Rear Admiral Nikolai Andreevich Arkas, made it clear that this was exclusively his diocese. In the dispute of both admirals, Grand Duke Konstantin unreservedly supported Arkas, instructing Butakov to ensure that the crews of commercial cruise ships of ROPiT were manned by the best officers and sailors. In addition, the society received a large loan from the government on favorable terms - for twenty years the company had to receive annual subsidies.

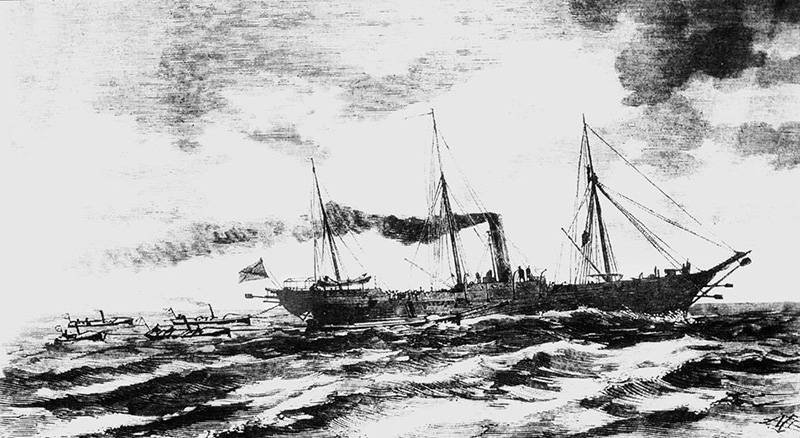

However, it was Grigory Ivanovich Butakov who constantly had to solve serious questions concerning the structure that was not subordinate to him. In the summer of 1858, the steamer ROPiT “Kerch”, serving the Trapezund-Odessa line, was attacked by boat smugglers. Commander of Kerch, Lieutenant Pyotr Petrovich Schmidt, a participant in the Crimean War, later the Rear Admiral and the father of that same Lieutenant Schmidt, organized a repulse, and the attack was repulsed.

The incident with "Kerch" greatly alarmed the management of the company, and it appealed for assistance to Butakov. The Directorate asked the rear admiral and the head of the naval unit to allocate a certain amount of guns in order to arm their ships to protect them from possible attack. In addition, Grigory Ivanovich was urged to allocate firearms and grappling weapons for crew members. The request was completely understandable, and in another situation would not cause any complaints.

However, Russia was in the grip of the Paris Peace Treaty, and the installation of weapons on commercial ships could cause a misunderstanding of respected Western partners who would immediately bombard Petersburg with threats poorly disguised as diplomatic notes. Butakov, although he had nothing to do with ROPiT, was forced to solve his problems.

He turned to Petersburg for clarification. The question of cannons, rifles and sabers was so ticklish that he rushed to the offices of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs through his general admiral. Prince Gorchakov, after weighing the pros and cons, cautiously agreed to a boarding weapon, expressing at the same time some concerns about guns, because of which respected Western partners might be offended. As a result, after listening to all the recommendations, explanations, explanations and instructions, Butakov singled out a number of boarding weapons for ROPiT ships.

While occupying the post of military governor of Nikolaev and Sevastopol, Butakov, as he could, tried to convey to the capital the state of affairs on the ground. Failure with the group Schwendner did not shake his self-righteousness. In 1859, he presented to the attention of Admiral-General Grand Duke Constantine a document entitled “The Secret Note on the Situation in the Black Sea Administration”. In it, the rear admiral outlined not only the true state of affairs in Nikolaev and Sevastopol, but also subjected to scrupulous analysis of the state of affairs in the maritime ministry itself. According to Butakova, everything was extremely neglected and was in the greatest decline. The main reason for this, Grigory Ivanovich, considered the decomposition of the bureaucratic apparatus, total theft and bribery. “Who, after the Sevastopol war, does not know that we have shine from above, rot from below!” - stated in a note at the end of which Butakov asked to send him to resign. However, the Admiral General outplayed the situation in his own way. Instead of providing support, he transferred Butakova to the Baltic Fleet at the start of 1860 for further service.

The first very difficult years after the Crimean War passed. Life at the Ingul shipyard almost froze: the fleet did not become - the shipbuilding also ceased. The few production facilities were planned to be used only for the planned replacement of a limited number of Black Sea corvettes. The time spent as governor of Nikolaev and the head of the port of Rear Admiral Grigory Ivanovich Butakov came to an end.

As in the shipyard, life in the city, formed around the ceased to function Admiralty, actually stopped. People began to massively leave the city. Already at the beginning of 1857, the urban community declined by a huge number for those times in 27 thousand people and continued to decrease. Zahahla commercial and trading activities.

And Nikolaev was waiting for a new governor who was traveling from St. Petersburg. This was the Vice-Admiral, Adjutant General Bogdan Aleksandrovich (Gotlieb Friedrich) von Glasenap. He was in that position until 1871, when, taking full advantage of the defeat of France in the war with Prussia, Russia regained the right to have a fleet in the Black Sea basin.

To be continued ...

Information