Electronic warfare. "War of the Magi". Part of 1

Night Luftwaffe bombers used to raid England

For a better understanding of how this secret war between Germany and Great Britain was prepared, it is necessary to go back several years and see how the Germans developed radio navigation systems. The first was the Lorenz company, which back in 1930 developed a system designed to land aircraft in poor visibility conditions and at night. The novelty was named Lorenzbake. It was the first course glide system based on the principle of beam navigation. The main element of Lorenzbake was a radio transmitter operating at 33,33 MHz and located at the end of the runway. The receiving equipment installed on the aircraft detected a ground signal at a distance of up to 30 km from the airfield. The principle was quite simple - if the plane was to the left of the runway, then a number of Morse code dots could be heard in the pilot's headphones, and if to the right, then a series of dashes. As soon as the car was on the right course, a continuous signal sounded in the headphones. In addition, the Lorenzbake system provided for two radio beacon transmitters, which were installed at a distance of 300 and 3000 m from the start of the runway. They broadcast the signals vertically upward, which allowed the pilot to estimate the distance to the airfield while flying over them and begin to descend. Over time, visual indicators appeared on the dashboard of German aircraft, allowing the pilot to get rid of the constant listening to the radio broadcast. The system turned out to be so successful that it found application in civil aviation, and later spread to many European airports, including the UK. Lorenzbake began to be transferred to military rails in 1933, when the idea came to use radio navigation developments to increase the accuracy of night bombing.

[/ Center]

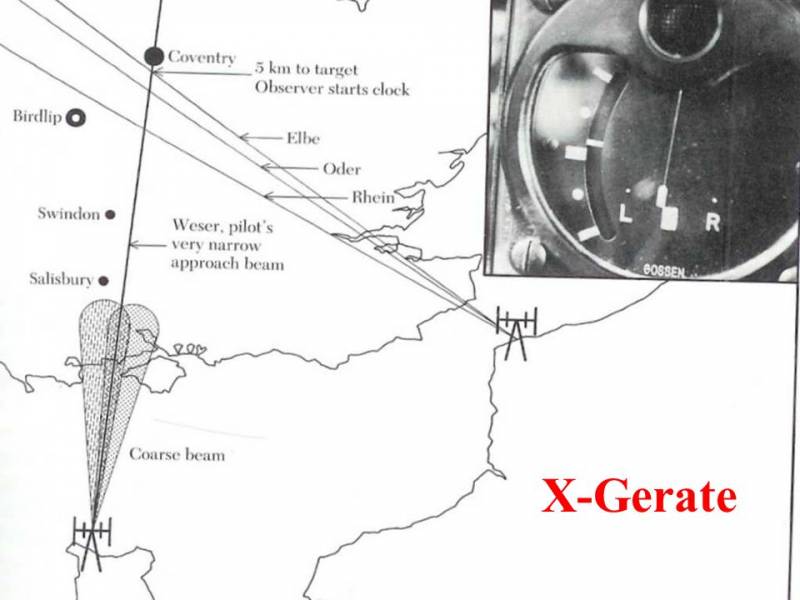

[/ Center]Luftwaffe bomber targeting principle at Coventry

Thus was born the famous X-Gerate system, which consisted of several Lorenz emitters, of which one emitted the main radionavigation beam, while others intersected it at specific locations in front of the bombing point. The planes were even equipped with automatic deadly cargo discharge equipment over the airstrike point. For the pre-war period, X-Gerate allowed planes to deliver night bombing with incredible accuracy. Already during the war, German bombers on the way to Coventry from the French Vonnes crossed several radionavigation rays under the names Rhein, Oder and Elba. Their intersections with the main driving beam, named after the river Weser, were mapped in advance to the navigator's map, which allowed for accurate positioning above night England. Through 5 km of flight, after crossing the last Elbe checkpoint, the German armada approached the target and automatically dropped its cargo on the center of the peaceful sleeping city. Recall that the British government knew in advance about the course of this action from Enigma decoders, but in order to preserve the ultra-secrecy, no measures were taken to save Coventry. Such precision targeting German bombers became possible after the Nazis occupied France and Belgium, on whose coasts were emitters. Their mutual arrangement allowed crossing the navigation rays over Britain almost at right angles, which increased the accuracy.

The fact that Germany is working intensively on an electronic system based on radioluchs was learned in Britain in 1938, when a secret folder was presented to the English naval attache in Oslo. Sources claim that he gave her a "prudent scientist" who did not want to give Germany priority in such sophisticated weapons. In this folder, in addition to information about X-Gerate, there was information about the nature of work in Peenemünde, magnetic mines, jet bombs, and more about a lot of high-tech. In Britain, at first they were taken aback by such a flow of secret data and did not particularly trust the contents of the folder - there was a high probability that the Germans slipped misinformation. Churchill put the point, who said: "If these facts are true, then this is a mortal danger." As a result, a committee of scientists was set up in Britain who began to implement the achievements of applied electronics in the military sphere. It is from this committee that all means of radio-electronic suppression of German navigation will be born. But the Hitlerite scientists were not idle - they understood perfectly that X-Gerate has a number of shortcomings. First of all, night bombers had to fly for a long time along a leading radio beam in a straight line, which inevitably led to frequent attacks by British fighters. In addition, the system was quite complicated for pilots and operators, which made it necessary to lose precious time for training bomber crews.

Avro Anson Radio Scout

The British first encountered the German 21 electronic radio navigation system on June 1940, when the pilot of Avro Anson, performing a standard radio reconnaissance patrol, heard something new in his headphones. It was a sequence of very clean and distinct points of Morse code, after which he soon heard a continuous signal. After a few tens of seconds, the pilot had already heard the dash sequence. So the German radio beam was directed by bomber aircraft to the cities of England. In response, British scientists have proposed a method of counteraction based on the continuous emission of noise in the X-Gerate radio band. It is noteworthy that for this unusual purpose the medical thermocoagulation apparatus, with which the hospital in London was equipped, perfectly suited. The device created electrical discharges that prevented enemy aircraft from receiving navigation signals. The second option was a microphone located near the rotating screw, which made it possible to transmit such noise at X-Gerate frequencies (200-900 kHz). The most advanced system was Meacon, the receiver and transmitter of which were located in the south of England at a distance of 6 km from each other. The receiver was responsible for intercepting the signal from X-Gerate, transmitting it to the transmitter, which immediately relayed it with a large signal gain. As a result, the German planes caught two signals at once - one of their own, which constantly weakened, and the second strong, but false. The automatic system, of course, was guided by a more powerful course beam, which took it away in a completely different direction. Many German "bombers" dumped their cargo into a clean field, and after using up their supply of kerosene, they were forced to board British airfields.

U-88-5, which the British landed with the whole crew on their airfield at night

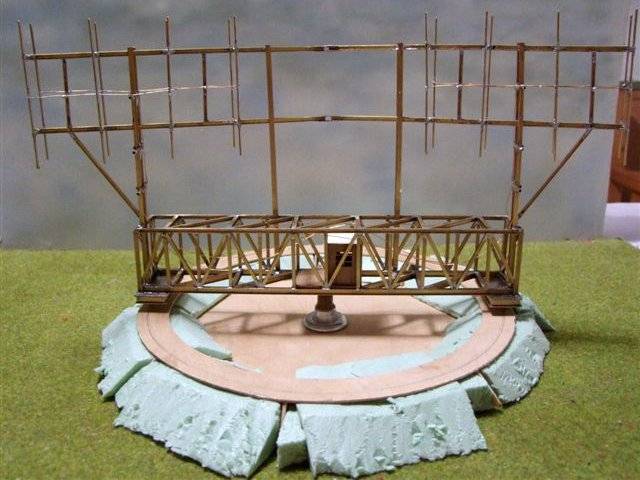

Modern scale model of the Knickebein emitter

The response of the German military machine to such British tricks was the Knickebein system (Curved leg), which got its name from the specific shape of the antenna-emitter. The actual difference from X-Gerate from Knickebein was that only two transmitters were used, which intersected only at the bombing point. The advantage of the “curve of the foot” was greater accuracy, since the sector of the continuous signal was only 3 degrees. X-Gerate and Knickebein were obviously used by the Germans for a long time in parallel.

Knickebein FuG-28a Signal Receiver

Bombing at night with Knickebein could be done with an error of no more than 1 km. But the British on the intelligence channels, as well as on materials from the downed bomber were able to quickly respond and created their own Aspirin. At the very beginning of the Knickebein system, the specialized Avro Anson aircraft plied the skies of Britain in search of Knickebein's narrowly focused beams and, as soon as they were fixed, the relay stations entered the scene. They selectively re-emitted a dot or a dash at greater power, which deflected the route of the bombers from the original one and again led them to the fields. The British also learned to fix the point of intersection of the rays of the Germans' radionavigation system and quickly raised fighters into the air to intercept. This whole set of measures allowed the British to withstand the second part of the Luftwaffe operation, connected with the night bombardments of England. But the electronic warfare did not end there, but only became more sophisticated.

Продолжение следует ...

- Evgeny Fedorov

- modellversium.de, war-only.com, slideplayer.com, airwar.ru

Information