Japanese musketeers

Then three Portuguese merchants were thrown by a storm on the shore of the island of Tangegashima, and this seemingly insignificant event became a truly gift of fate for the whole of Japan. The Japanese were struck by the very appearance of the “long-nosed barbarians”, their clothes and speech, and what they held in their hands - “something long, with a hole in the middle and an ingenious device closer to the tree, which they rested on their shoulder ... then fire flew out of it , there was a deafening thunder and a lead ball at a distance of thirty paces killed a bird!

Daime of Tanegashima Island Tochikata, having paid a lot of money, bought two "teppo", as the Japanese called this strange weapon, and gave it to his blacksmith to make an analogue no worse. Since the Portuguese fired from “this” without a stand, it should be assumed that it was not a heavy musket that fell into the hands of the Japanese, but a relatively light arquebus, the dimensions and weight of which allowed hand-held shooting. However, it was not possible to make an analog at first. The Japanese blacksmith was able to forge the barrel without much difficulty, but it turned out to be too much for him to cut the internal thread in the back of the barrel and insert the “plug” there. However, a few months later, another Portuguese came to the island, and here it is, as the legend tells, and showed the Japanese masters how to do it. All other details were easy to do. So very soon, on the island of Tanegashima, the production of the first in stories Japan firearms. Moreover, from the very beginning, the production of "tanegashima" (the Japanese began to call it that way), went at an accelerated pace. For six months, 600 Arquebuses was made on the island, which Totikata immediately sold out. As a result, not only enriched himself, but also contributed to its widespread distribution.

Modern Japanese "musketeers" - participants of demonstrations with shooting.

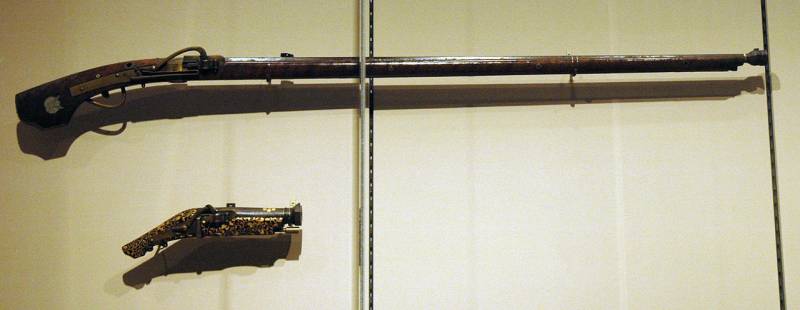

And this is the real “Tanegashima” of the Edo era from the Tokaido Museum, in Hakon.

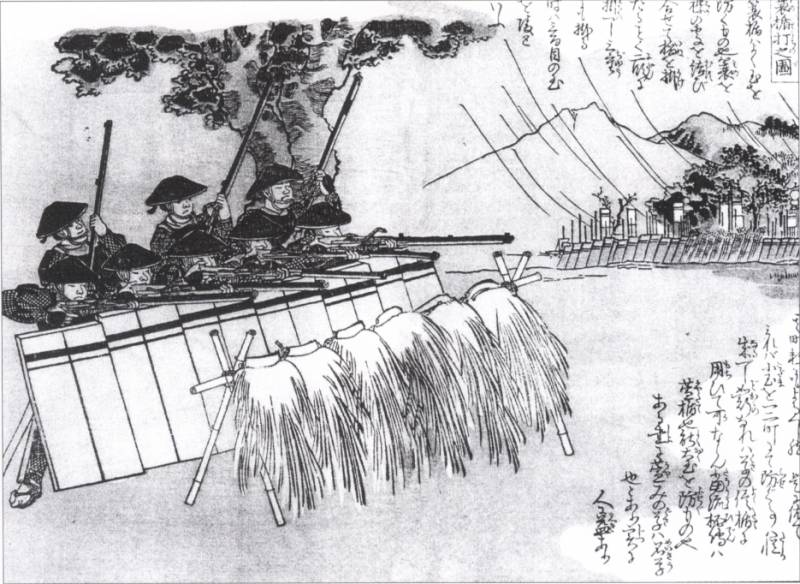

Already in 1549, daimyo Shimazu Takahisa applied tanegasimu in battle, and then every year its popularity grew more and more. Takeda Shingen, for example, already in 1555 year, paying tribute to these weapons, bought at least 300 such arquebuses, and already Oda Nobunaga (this one loved everything European, starting with wine and ending with furniture!) 20 years later had 3000 arrows at his disposal in the battle of Nagashino. Moreover, he used them very modernly, having built in three lines so that they fired over each other’s heads, and from the attacks of Katsuri's cavalry they would be covered by a lattice fence.

Japanese teppo from the museum in the castle of Kumamoto. In the foreground is the “handgun” of kakae-zutsu.

The same museum, the same arquebus, but only the rear view. The device of their wick locks is clearly visible.

Moreover, it should be noted that, although for some reason it is considered otherwise, in fact, the samurai in the Sengoku era did not at all disdain to use teppo and use it personally. That, they say, this is a “vile” and unsuitable weapon for a samurai. On the contrary, they very quickly appreciated its advantages and many of them, including the same Oda Nabunaga, turned into well-aimed shooters. The continuous wars of all against all just at that time caused a truly mass production of this type of weapon, but they, of course, did not like the fact that it began to fall even into the hands of the peasants. And very soon the number of arquebuses in Japan exceeded their number in Europe, which, by the way, was one of the reasons why neither the Spaniards nor the Portuguese even tried to conquer it and turn it into their colony. Moreover, the Japanese achieved real mastery in the manufacture of their teppo, as evidenced by the samples of these weapons that have come down to us and are stored today in museums.

Tanegashima and pistora. Museum of Asian Art, San Francisco.

Note that the word “teppo” in Japan denoted a whole class of weapons, but at first it was the arquebus made according to the Portuguese model that was called, although such a name as hinawa-ju or “wick gun” is also known. But over time, Japanese craftsmen began to make their own gunpowder weapons, no longer similar to the original samples, that is, they developed their own style and traditions of its production.

Samurai Niiro Tdamoto with teppo in hand. Uki-yo Utagawa Yoshiyku.

So what is the difference between Japanese arquebus and European ones? Let's start with the fact that they have the reverse arrangement of the serpentine (trigger) with hibasami for the hinawa wick. Among the Europeans, he was in front and leaned back "toward himself." The Japanese - he was attached behind the breech and leaned back "from himself". In addition, it seemed to them, and not without reason, that the burning wick, located at a close distance from the shelf with seed gunpowder, called hidzara, was not the best neighborhood, and they came up with a sliding hibuta cover that reliably closed this shelf. The lid moved and only after that it was necessary to pull the trigger to fire a shot. The barrel length of the Japanese arquebus was approximately 90 cm, but the calibers varied - from 13 to 20 mm. The stock was made of red oak wood, almost the entire length of the barrel, which was fixed in it with traditional bamboo pins, just like the blades of Japanese swords, which were attached to the handle in a similar way. By the way, the locks of Japanese guns were also fastened on pins. The Japanese did not like screws, unlike the Europeans. A ramrod is a simple wooden (karuka) or bamboo (seseri) recessed into the box. At the same time, a feature of the Japanese gun was ... the absence of a butt as such! Instead, there was a daijiri pistol grip, which was pressed against the cheek before firing! That is, the recoil was perceived on the barrel and then on the hand, went down and moved back, but the gun did not give back to the shoulder. That is why, by the way, the Japanese were so fond of faceted - six and octagonal trunks. They were both stronger and heavier and ... better extinguished recoil due to their mass! In addition, their edges were convenient to draw. Although, we also note this, the decoration of the trunks of Japanese teppo did not differ in special frills. Usually they depicted monks - the emblems of the clan that ordered the weapons were covered with gilding or varnish.

Bajo-zutsu is a rider's pistol, and richly trimmed. Edo Epoch. Anne and Gabriel Barbier-Muller Museum, Texas.

The Tandzutsu is an Edo-era short pistol. Anne and Gabriel Barbier-Muller Museum, Texas.

The details of the locks, including the springs, were made of brass. It did not corrode like iron (which is very important in the Japanese climate!), but most importantly, it allowed all the details to be cast. That is, the production of locks was fast and efficient. Moreover, even brass springs turned out to be more profitable than steel European ones. How? Yes, those that were weaker !!! And it turned out that the Japanese serpentine with a wick approached the seed more slowly than the European one, and it happened to hit the shelf with such force that ... it went out at the moment of impact, without even having time to ignite the gunpowder, which caused a misfire!

For sniper shooting, the Japanese made such long-barreled shotguns with barrels 1,80 mm long and even 2 meters. The Nagoya Castle Museum.

The Japanese arquebuses had sights, a saki-me-ate front sight and ato-me-ate rear sight, and ... the original, again varnished, boxes covering the lock from rain and snow.

Niiro Tadamoto with cocoa jutsu. Uki-yo Utagawa Yoshiyku.

Hitting a cocoa-zutsu explosive projectile in a tate shield. Uki-ё Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

As a result, Japanese arquebuses became more massive than European ones, although they were still lighter than muskets. In addition, the Japanese came up with the so-called "hand guns" or kakae-zutsu, somewhat similar to European hand grenade launchers used since the XNUMXth century. But although their similarity is undeniable, the Japanese design is very different from the European one, and is an independent invention. The European mortar always had a stock and behind it a short barrel designed for throwing matchlock grenades. The Japanese jutsu did not have a butt, but they fired fired clay balls and lead cannonballs from it. The barrel was quite long, but the powder charge was small. Thanks to this, it was possible to shoot from the "hand gun" really, holding it in hand. The payoff was great, of course. The “gun” could be pulled out of his hands, and if the shooter held it tightly, then it would not overturn him on the ground. And, nevertheless, it was possible to shoot in this way from it. Although another method was also used: the shooter laid out a pyramid of three bundles of rice straw on the ground and laid a “cannon” on it, resting the handle on the ground or another sheaf, lined with two stakes from behind. Having set the desired angle of inclination of the barrel, the shooter pulled the trigger and fired a shot. The bullet flew along a steep trajectory, which made it possible to fire at enemies hiding behind the walls of the castle in this way. It happened that gunpowder rockets were inserted into the barrel of a kakae-zutsu and thus greatly increased the firing range.

Guns from the arsenal of Himeji Castle.

Known were the Japanese and pistols, called them a pistol. Yes, they were wicked, but were used by samurai riders in the same way as European reiters. They were heading in the direction of the enemy, and, approaching him, they almost fired a shot, and then returned back, reloading their weapons on the move.

Asigaru, hiding behind tate shields, fire on the enemy. Illustration from Dzhohyo Monogatari. National Museum, Tokyo.

Another very important invention that increased the rate of fire of Japanese weapons was the invention of specially designed wooden cartridges. It is known that at first gunpowder was poured into the same arquebuses from a powder flask, after which a bullet was pushed towards it with a ramrod. In Rus', archers kept pre-measured powder charges in wooden "cartridges" - "chargers". Where they appeared before - in our country or in Europe, it is difficult to say, but they appeared and it became more convenient to immediately load the squeaks and muskets. But the bullet still had to be taken out of the bag. The solution to the problem was a paper cartridge, in which both a bullet and gunpowder are in one paper wrapper. Now the soldier bit the shell of such a cartridge with his teeth (hence the command “bite the cartridge!”), poured a certain amount of gunpowder onto the seed shelf, and poured the rest of the gunpowder together with the bullet into the barrel and tamped it with a ramrod, using the paper itself as a wad cartridge.

The Japanese invented a “charge” with two (!) Holes and a conical channel inside. At the same time, one of them was closed by a spring-loaded lid, while the other hole was a “plug” served by the bullet itself!

"Varnished boxes against the rain." Engraving Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Well, now let's imagine that we are “Japanese Musketeers” and we have to fire at the enemy.

So, standing on one knee, at the command of the co-gasir (“junior lieutenant”), we take out our wooden cartridge from the cartridge bag, open it and pour all the gunpowder into the barrel. And you just need to press the bullet protruding from it with your finger, and it will instantly slide into the barrel. We remove the cartridge and ram the gunpowder and bullet with a ramrod. We remove the ramrod and fold back the cover of the powder shelf. Smaller seed gunpowder is poured onto a shelf from a separate powder flask. We close the cover of the shelf, and blow off the excess gunpowder from the shelf so that it does not flare up before the allotted time. Now fan the flame at the tip of the wick wrapped around the left hand. The wick itself is made of fibers of cedar bark, so it smolders well and does not go out. Now the wick is inserted into the serpentine. Ko-gashiru commands the first aiming. Then the shelf lid opens. Now you can make the final aim, and pull the trigger. The burning wick will gently press against the gunpowder on the shelf and a shot will occur!

The armor of the warrior ashigaru works of the American reenactor Matt Poitras, already familiar to VO readers in his armor of the soldiers of the Trojan War, as well as the Greeks and Romans.

It is interesting that the Japanese also knew the bayonet-type blade bayonet - dzyuken and the spear-shaped bayonet juso, as well as guns and pistols with wheel and flintlocks. They knew, but since they entered the era of the Edo world, they did not feel any need for them. But now, in peacetime, it was the sword that became the main weapon of the samurai, and the guns that the peasants could successfully fight with, faded into the background. However, it happened, we emphasize, this was already in the Edo era!

Information