Rifles by countries and continents. Part of 11. Like a ross rifle, I almost became Huot's machine gun.

Machine gun Huota. (Army Museum in Halifax, Nova Scotia Province)

As you know, improving is easier than re-creating. As a rule, in the course of operation, many people notice the shortcomings of a particular structure and, as they are talented and able, try to correct them. But it also happens that someone’s idea inspires another person to create a structure that is already so “something new” that it deserves a fundamentally new attitude. And the need in such cases is usually the "best teacher", since it is she who makes the "gray cells" work with a voltage greater than usual!

And it was so that when Canadian units went to Europe to fight for the interests of the British crown during the First World War, it immediately turned out on the battlefields that the Ross rifle, although it was shooting accurately, was completely unsuitable for military service. Its straight gate was very sensitive to contamination, and quite often, in order to distort it, we had to beat it with the handle of the deminer blade! Many other annoying incidents happened to her, because of which Canadian soldiers simply began to steal Enfield rifles from their English "colleagues", or even to buy for money. Anything - just not Ross! Moreover, difficulties with ammunition did not arise here, since they had the same ammunition. And it ended with the fact that the Ross rifles were left only to snipers, and in the linear parts they were replaced by “Lee-Enfilds”.

But now there is a new problem. They began to miss the light machine guns. Manual Lewis machine guns were required by everyone - the British and Russian infantry, aviators, tankers (the latter, though not for long), Indian bass, as well as all other parts of the dominions. And no matter how hard the British industry tried, the output of these machine guns was not enough.

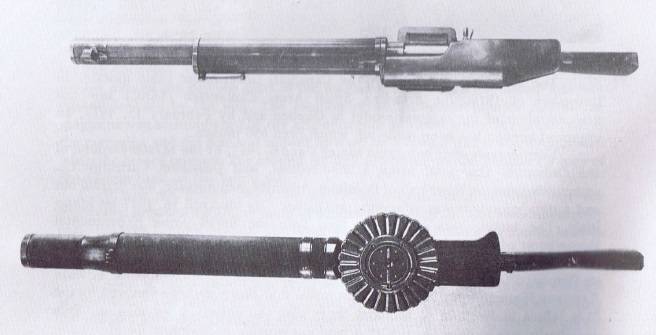

“Huot” (above) and “Lewis” (below). Views from the top. The characteristic flat “boxes” on the closures contained: the “Lewis” system of the magazine's rotation levers, the “hoot” - the gas piston damper and the details of the connection between the bolt and the piston. (Photos from the Museum Museum of the Seafort Highlanders in Vancouver)

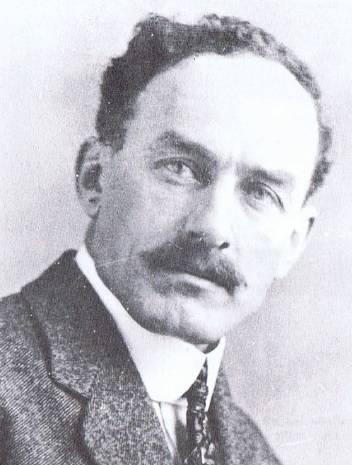

And so it happened that the first to figure out how to get out of this difficult situation was Joseph Alphonse Hoot (Wot, Huot), a machinist and a blacksmith from Quebec. Born in 1878, he was a big and strong man (not surprising for a blacksmith), more than six feet tall and weighing 210 pounds. The man, as they write about him, he was not only strong, but also hardworking, stubborn, but unnecessarily trusting of people, which in business does not always help, but more often than not, it hurts!

Joseph Alphonse Huot (1918)

At first, he viewed his work on the automatic rifle as a hobby. But when World War I broke out, his interest in arms became more serious. He began working on his project from the middle of 1914 onwards and worked until the end of 1916 onwards, continuously improving it. Its development was protected by Canadian patents, #193 724 and #193 725 (but to my great regret, not a single text, nor images from any of them are available to the Internet through the Canadian online archive).

His idea was to attach to the rifle of Charles Ross gas tube with a gas piston on the left side of the barrel. This would allow this mechanism to be used to activate the shutter of a Ross rifle, which, as is well known, had a reloading knob on the right. Such an alteration would be technically quite simple (although the devil is always hiding in details, because you need to make such a mechanism work smoothly and reliably). In addition to the gas piston, Huot designed the ratchet and the feed mechanism of the ammunition from the drum mechanism to the 25 cartridges. He took care of the cooling system of the barrel, but he didn’t overwork, but simply took and used the ingeniously invented Lewis machine gun system: a thin-walled casing with a narrowing at the muzzle of the barrel recessed inside this casing. When fired into a “pipe” of such a design, an air draft always occurs (on which all inhalers are based), so if you install a radiator on the barrel, this air flow will cool it. On a Lewis machine gun, it was made of aluminum and had longitudinal fins. And Huot repeated it all on his model.

“Huot” (above) and “Lewis” (below). (Photos from the Museum Museum of the Seafort Highlanders in Vancouver)

Until September 1916, Huot refined his sample, and 8 September, 1916, met with Colonel Matish in Ottawa, after which he was hired as a civilian in the Experimental Division of Small Arms. True, although this ensured the continuation of work on his weapon, working for the government also meant a catastrophe for any of his hopes of commercial gain from this work. That is, now he could not sell his sample to the government, since he worked for him for a salary! The situation, as we know, has already taken place in Russia with Captain Mosin, who created his own rifle during working hours as well, being released from service as such.

As a result, Huot completed the creation of a prototype and in December 1916 of the year demonstrated it to military officials. 15 February The 1917 of the year was demonstrated by an improved version of the machine gun, which has an 650 firing rate per minute. Then they fired at least 11 000 cartridges from a machine gun - so he passed the test for survivability. Finally, in October, 1917 of the Year of Huot and Major Robert Blair were sent to England to be tested there, so that this machine gun was approved by the British military.

They sailed to England at the end of November, arrived in early December 1917 of the year, and the first tests were launched on 10 in January 1918 of the year at the Royal Enfield Small Arms Factory. In March, they were repeated, and they showed that Huota's light machine gun has clear advantages over Lewis, Farquar-Hill and Hotchkiss machine guns. Tests and demonstrations continued until the beginning of August 1918 of the year, although on July 11 of the year the British military officially rejected this sample.

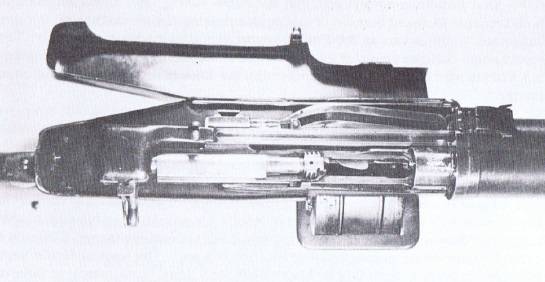

The device automatic machine gun Huota. (Photos from the Museum Museum of the Seafort Highlanders in Vancouver)

Despite the fact that it was decided to reject the Huot machine gun, compared with the Lewis machine gun, it was recognized to be quite competitive. It was more convenient when firing from a trench and it could be quickly brought into action. Huot's machine gun was easier to disassemble. It was found that it was less accurate than the "Lewis", although this was probably due to the fact that both the sight and the front sight were attached to the cooler case, which, as it turned out, vibrated heavily when fired. In Enfield, they complained about the shape of the butt, which made it difficult to hold the weapon well (which is not surprising given the volume and location of the gas valve cover, which was far back). As a disadvantage, the store was marked for only 25 cartridges, which was empty in 3,2 seconds! To speed up store equipment, special 25 charging clips were provided, so it was easy to recharge it. True, there was no fire interpreter, so it was impossible to fire a single machine gun from a machine gun! On the other hand, it was noted that it is smaller than the “Lewis”, and can shoot in an inverted position, whereas he could not do that! It was noted that it was the only weapon tested that could remain in working condition after immersion in water. Lieutenant General Arthur Curry, commander of the Canadian Expeditionary Corps, reported that every soldier who tried the Huot automatic rifle was satisfied with it, so on October 1 1918 he wrote a request for 5000 copies, arguing that there was nothing for his soldiers oppose a large number of German light machine guns.

Huota machine gun. (Photo from the Museum of the regiment of the sittort Highlanders in Vancouver)

For production, the fact that the Huot machine gun had 33 parts that were directly interchangeable with the details of the Ross M1910 rifle, plus 11 parts of the rifle, which would have to be redone, and 56 parts that would have to be done from scratch was very beneficial. In 1918, the cost of one copy was only Canadian 50 dollars, while Lewis was worth 1000! Its mass was 5,9 kg (without cartridges) and 8,6 (with curb magazine). Length - 1190 mm, barrel length - 635 mm. Rate of fire: 475 shots / min (technical) and 155 (combat). The initial speed of the bullet 730 m / s.

But why then was the weapon rejected, despite such promising test results? The answer is simple: with all its positive data, it was not much better than Lewis to justify the cost of refitting producing enterprises and retraining soldiers. And, of course, after the end of the war, it immediately turned out that the Lewis machine guns of the army in peacetime were sufficient, and there was no need to look for additional such weapons.

Major Robert Blair with Huot's rifle, 1917 year. (Photos from the Museum Museum of the Seafort Highlanders in Vancouver)

Unfortunately, due to all these circumstances, the personal condition of Huot was in a deplorable situation. Any agreement on the payment of royalties by the Government of Canada depended on the formal adoption of weapons, so when it was rejected, he only had the salary he received while working on his brainchild. Investments in the amount of their own 35 000 dollars, which he invested in this project, in fact, flew into the tube. Huot demanded at least to return this money to him and eventually received compensation in the amount of 25 000 US dollars, but only in 1936 year. His first wife died a few days after giving birth in the 1915 year, and he married again after the war, marrying a woman with 5 children. He worked as a worker and builder in Ottawa. He lived until June 1947 of the year, continuing to be engaged in inventing, but he never achieved such success, which he achieved with his light machine gun!

It is known that all the Huot machine guns were made 5-6 pieces and today they are all in museums.

Продолжение следует ...

- V. Shpakovsky

- The same "Spencer." Rifles by country and continent - 10

Rifles for South America (Rifles by countries and continents - 9)

Rifles - the heiress of revolver guns (Rifles by countries and continents - 8)

Great Gun Drama USA (Rifles by Countries and Continents - 7)

Great Gun Drama USA (Rifles by Countries and Continents - 6)

Great Gun Drama USA (Rifles by Countries and Continents - 5)

Great Gun Drama USA (Rifles by Countries and Continents - 4)

Great Gun Drama USA (Rifles by Countries and Continents - 3)

Great Gun Drama USA (Rifles by Countries and Continents - 2)

Rifle for Simo Hyahuya (continuation of the theme “Rifles by countries and continents” - 1)

Information