The most expensive helmets. Helmet of Gisborough. Part three

Helmet of Gisborough. Front view. Looking closer, you can see an engraved figure of a deity in the center.

Obviously, the find was "intentionally buried in a hole dug for this purpose, where it was found." Thomas Richmond, a local historian, mistakenly identified the find as belonging to the “late Celtic or early Anglo-Saxon period.” In 1878, Frederick B. Greenwood, who owned the land on which this find was made, transferred it to the British Museum. In the museum, it was restored and it turned out that in fact it is nothing more than an ancient Roman helmet. It is currently on display in the Roman Britain section of the 49 room. Similar helmets have been found elsewhere in Europe; the closest continental parallel is a helmet found in the Saone River at Chalon-sur-Saone in France in the 1860s. The Helmet of Gisborough gave the name to a certain type of Roman helmets, called the type of Gizboro, which can be distinguished by three pointed crests on the crown, giving it the appearance of a crown.

Helmet of Gisborough. Front view left.

Initially, the helmet was equipped with two protective headlamps, which, however, were not preserved. Only the holes with the help of which they were attached, and which are visible in front of the protective headphones of the helmet, are visible. The helmet is lavishly decorated with engraved as well as relief figures, indicating that it could be used as a parade or for hippik tournaments gymnasium. But there is no reason to think that it was not intended for battle. The helmet was found on a bed of gravel, far from the famous places of the Roman presence, so it is obvious that he came to this place by chance. After he was found, he was presented to the British Museum in London, where he was restored and where he is currently on display.

Helmet of Gisborough. Side view, left.

The helmet is made of bronze in the III century AD. On it are engraved figures of the goddess Victoria, Minerva and the god of Mars, that is, all the patrons of military affairs. Between the figures of deities, galloping horsemen are depicted. The helmet hub has three diadem-like protrusions that make it look like a crown. On the outer edge of these protrusions are wriggling snakes, whose heads are found in the center, forming an arch over the central figure of the god Mars. In the back of the helmet there are two small umbonas, located in the center of the relief colors. The sides and top of the helmet are decorated with feather reliefs. By its design, it is similar to a number of other artifacts similar to it, found in Worthing, Norfolk and Chalon-sur-Saone in France. Despite its relative subtlety and rich decoration, it is believed that such helmets could be used in battle, and not only at parades or in hippik competitions, gymnasium.

Helmet of Gisborough. Back view. Two umbo are clearly visible.

The helmet is still a mystery. For some reason it was flattened and buried in the ground away from any other ancient Roman objects known to us; and it remains unclear why they did not bury him completely, why they led him to such an unsuitable state for anything ?! In the vicinity there was neither a fort nor a fortress. Consequently, this helmet was brought here from afar. But if it was a sacrifice to some pagan gods, then again it is not clear why it was to spoil it?

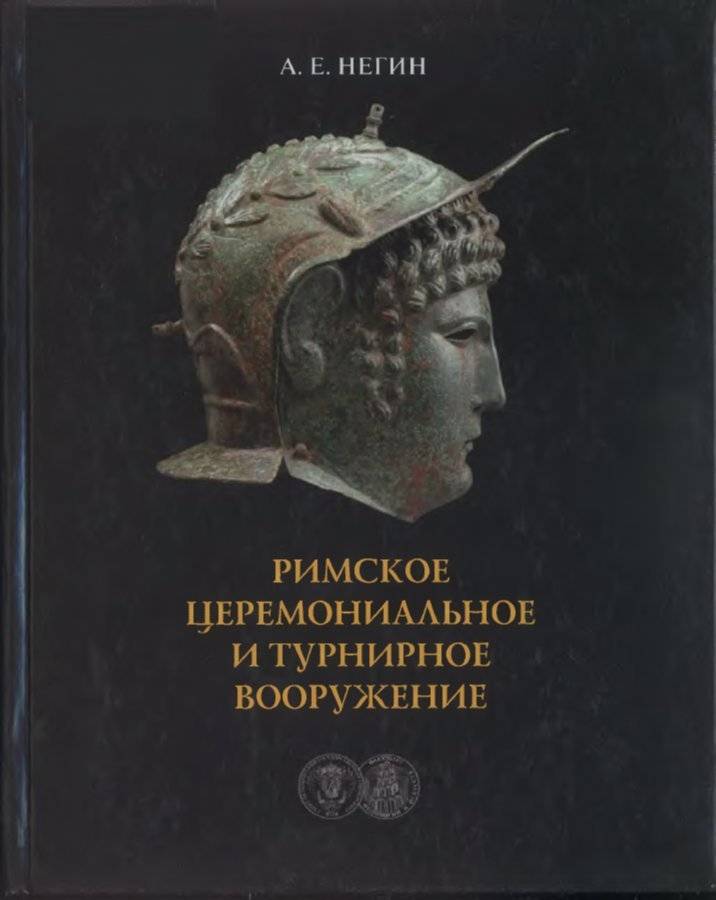

Those who wish to deepen their knowledge of this topic can recommend this book: Negin, A. Ye. Roman ceremonial and tournament weapons.

Still interesting is the question of how well the Roman "ceremonial" helmets could serve as protection in battle. This question interested the Russian historian A.E. Negin, who examined him in his monograph "The Roman Ceremonial and Tournament Armament", in which he also refers to the experiments of M. Yunkelman.

The figure of the god Mars on the sill of the helmet.

The latter noted that helmets with face masks of the 1st c. usually made of a fairly thick iron sheet, and if so, then in battle they could easily be used. For example, one of the facial masks found has a thickness of 4 mm, and for a mask from Mainz it is equal to 2 - 3 mm, that is, it is quite enough to protect the face from impact. Helmet crowns II-III centuries. It was also made of sheet metal of sufficient thickness, besides they had hammered images, that is, their protrusions could soften even more the blows struck on the helmet. We know that corrugated or grooved Maximilian armor of the 15th - 16th centuries. were six times stronger than armor with a smooth surface, so here everything was exactly the same as in the Middle Ages.

Mask from “Helm from Nijmegen” (“type Nijmegen”), the Netherlands. Iron and brass, the Flavian era (possibly hidden during the uprising of the Batavians of 70). The helmet was found on the south bank of the river Waal near the railway bridge. Inside it were two patches that did not belong to the specimen. Based on this, it can be assumed that the helmet is a sacrificial gift thrown into the river. From the helmet remained only edge with a bronze lining. On the frontal part there are five gilded busts (three women and two men). The inscription CNT is scratched on the left ear cushion, and the mask on the right cheek is MARCIAN ... S. The lips and eyelids have traces of gilding. Under the ears, there are remnants of rivets for fastening the mask to the helmet by means of a belt located above the nazatylnik. (Nijmegen, Museum of Antiquities)

Bronze masks of many helmets have a thickness from 0,2 to 2 mm. M. Yunkelmann conducted experiments on the firing of armor of such thickness with arrows from a distance of 2 m, threw at them a spear-gastu from the same distance and struck them with a sword-spat. At first, the experiment was carried out with a flat raw sheet of 0,5 mm thickness. An arrow pierced through it and went out on 35. A spear managed to pierce this sheet on 12. See After a sword strike, a dent appeared in it about 2 cm deep, but it was not possible to cut through it. An experiment with a brass sheet 1 mm thick showed that an arrow penetrates 2 cm into it, a spear into 3 cm, and a sword creates a dent about 0,7 cm in depth. However, it should be taken into account that the impact was made on a flat surface and at a right angle, while the impact on the curved surface of the helmet, as a rule, did not reach the goal, since the thickness of the metal was actually greater due to the difference in the product profile. In addition, leather and felt, used as a lining, allowed to neutralize the blow.

The only full Roman helmet (including the mask), not counting the “Crosby Garrett helmet”, found in the UK in the Ribchester area back in 1796 year. Part of the so-called "Ribchester treasure". Together with him was found a bronze figure of the Sphinx. But Joseph Walton, who found the treasure, gave her children to one of the brothers to play, and they, of course, lost it. Thomas Dunham Whitaker, who examined the treasure after the discovery, suggested that the sphinx had to be attached to the top of the helmet, because it had a curved base that echoed the curvature of the surface of the helmet and also had traces of solder. The discovery of the Crosby Garret helmet in the 2010 year, with a winged griffin, confirmed this assumption. (British Museum, London)

Subsequent experiments were carried out with a profiled plate that imitated a roman helmet crown, minted in the form of curly hair, and had a thickness of 1,2 mm. It turned out that most of the strikes on this detail did not reach the goal. Weapon slipped and left only scratches on the surface. The arrow sheet of metal was pierced to the depth of the entire 1,5, see the Spear, falling into the profiled sheet, most often rebounded, although with a direct hit it punched the plate to a depth of 4 mm. From the blows of the sword on it remained dents no more than a depth of 2 mm. That is, both helmets and masks made of metal of the specified thickness and covered in addition with chased images, quite well protected their owners from most of the weapons of that time. The greatest danger was that of a direct hit by an arrow. But with such a hit, the arrows pierced both chain mail and even scaly shells, so no type of armor of that time guaranteed absolute protection!

As for wearing comfort, a helmet with a mask was more comfortable than a knight's tophelma, since the mask fit snugly to the face, and since the eye openings are close to the eyes, the view from it is better. When the jump air flow is quite sufficient, but annoying lack of blowing the face of the wind. Sweat runs from face to chin, which is unpleasant. At samurai on masks for removal of sweat special tubes were thought up. But for some reason, the Romans did not think of it.

Helmet of Gisborough. The cutout for the ear is clearly visible, with a chased roller around it.

Audibility in the helmet is bad. And the protection of the neck itself is absent. But this was typical of all Roman helmets, which had only a backsight in the rear, and only cataphracts and clibanariums had barmia. The conclusion made by M. Yunkelmann and A. Negin, is that helmets with masks provided the Roman soldiers with very good protection and could be used both at parades and in battles!

To be continued ...

Information