The defeat of the Italian army in the Battle of Caporetto

Heavy defeat of the Italian army led to the fall of the government and the change of the Supreme Commander Luigi Cadorna. The situation was critical and that Italy did not fall, the Allied command sent French and British divisions to help. During the heavy November battles, the front was able to stabilize. The Italian army lost the ability to conduct offensive operations for a considerable time, which allowed Austria-Hungary to hold the front for some time.

General situation before the battle

The situation of Italy and Austria-Hungary in the autumn and winter of 1917 was similar - both powers had a lot of difficulties. Russia actually no longer existed as an ally of the Entente. The Russian army collapsed and ceased to be the main threat to the Habsburg Empire. The Austrian General Staff could focus its main efforts on the Italian front. The United States sided with the Entente, but could not immediately compensate for the absence of the Russian army, since they did not hurry with the transfer and deployment of the army in the European theater.

The unlimited submarine war waged by Germany had a negative effect on the economy and population of Italy. The country had a certain dependence on the supply of food and raw materials for industry. Italy’s merchant fleet was small, so ship losses were sensitive for him. The Italian population suffered greatly from the vicissitudes of war. Part of the society advocated the conclusion of peace. The Pope’s Encyclical of 15 of August 1917 of the year spoke of a “useless slaughter” and offered the mutual withdrawal of troops from the occupied territories and the restoration of Belgium as a basis for peaceful negotiations. Questions about Alsace-Lorraine and the disputed Italian territories were to be resolved by the parties concerned. Germany rejected these proposals: Berlin considered the issue of the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine non-negotiable and refused to re-establish Belgium. In turn, London and Washington did not want peace with Germany, since they had already seen the victory and divided the "skin of the German bear."

The position of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, both economic and military, was worse than that of Germany. The last battles on the Italian front demoralized her army. The High Command expressed doubts that Austria would endure a new battle at the Isonzo. Vienna turned for help to Berlin. The German command, in order not to lose its main ally, decided to support the offensive of the Austro-Hungarian army in Italy. The Allies were going to inflict a decisive defeat on the Italian army, which could bring Italy out of the war.

The Italian army outwardly significantly strengthened compared with 1915. Compared to 1915, the number of personnel doubled - instead of 35 divisions on the Italian front, there were 65 divisions, another 5 in Albania and Macedonia. The military material base of the armed forces was seriously strengthened. So, the number of heavy guns increased from 200-300 (there were a lot of old, obsolete types) to 1800. Motorized transport made it possible to carry out fast troop transfers; aviationmilitary industry produced more weapons, ammunition and other military equipment.

The problem was in the moral factor. The troops were tired of the futile and extremely bloody fuss on a rather isolated front. The defense of the enemy had to literally gnaw, promotion for several kilometers was considered a great victory. The slow, heavy progress in the rocky desert, which had to be paid at great cost, exhausted the soldiers. The war of attrition caused feelings of despondency and hopelessness. The general morale of the Italian army, like the Austro-Hungarian, was heavy. The question was who would collapse faster. Changed the staff of the army, as in other warring armies. A large number of personnel officers, reserve officers and volunteers - people more or less trained, full of enthusiasm (they were going to liberate Italian lands!), Died, or were seriously injured, some after recovery were used to train personnel or go to headquarters. Wartime officers were worse prepared, morally worse. Many were made officers not by their own will, but by compulsion, as people with a good education. Many of them were still very young people who had just graduated from school and had been studying at the cadet school for several weeks. It is clear that part of the Italian intelligentsia was infected with defeatist sentiments, while others had “no milk on their lips dried up,” and soldiers who had already gone through fire and water did not respect them.

Many old school generals, who closely communicated with their subordinates, walked in the front ranks, also fell. Some of the generals were dismissed for mistakes, although they had better training and experience, unlike most new commanders. This led to a gap between the commanders and the rank and file. Higher command in general has come off the ordinary mass, it has ceased to understand that people of flesh and blood are leading the war. Part of the generals, remembering the old wars, which usually lasted for weeks and months, forgot that soldiers needed rest, entertainment, and home leave. Other generals made a career in the war, looked at the war and the soldiers as a means to grow up the career ladder. This led to a policy of silencing unpleasant information, smoothed the overall picture, tried to isolate the good and keep silent about the bad.

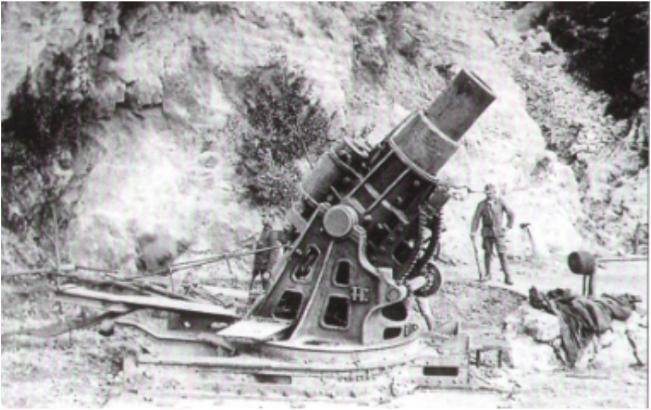

Austro-Hungarian 305-mm cannon

Plans for the Austro-German Command

The Austrian high command, as noted above, doubted the ability of the army to withstand the new strong blow of the enemy. As a result, the Austrians decided that passive defense could lead to defeat, and a fatal, complete disaster. Therefore, it is necessary to attack themselves before it is too late. But for a decisive offensive operation, the help of the German army was needed. Already 25 August 1917, when the battle on the Beinsitz plateau was still going on, the Austrian high command asked the German bid for help.

26 August Austrian Emperor Karl Franz-Joseph wrote to Kaiser Wilhelm: “The experience of our eleventh battle convinces me that the twelfth battle will be a very difficult task for us. My generals and my troops believe that it is best to overcome all difficulties by going on the offensive. Change the Austro-Hungarian units on the eastern front with the German ones, so that the first ones are freed. I attach great importance to the conduct of an offensive against Italy by some Austro-Hungarian units. The whole army calls this war our war; all officers are brought up on the feeling of war against the primordial enemy, transmitted to them from their fathers. But we would gladly accept German artillery, especially heavy batteries. A successful strike against Italy will accelerate the end of the war. ” The German emperor Wilhelm replied that in an operation against "perfidious Italy" Austria could count on Germany. It was relatively calm on the Western Front, and there was no serious threat in the East.

29 August 1917, General Waldstetten, presented the plan of the operation to the head of the Austrian General Staff, Artsu von Straussenburg. The main attack included an offensive from Tolmino in the direction of the Yudrio valley and on Cividale. Auxiliary actions were planned from the Plezzo basin towards Nizezone. To do this, it was planned to allocate 13 Austrian and German divisions. Ludendorff did not initially support the idea of a major offensive operation. He feared to reduce forces on the French front and did not hope to achieve a decisive result in Italy, with a significant expenditure of troops. Ludendorff would prefer a new attack on the Romanian front in order to finish off Romania and provide an additional inflow of food resources. As a result, Hindenburg and Ludendorff still approved this plan, although it was thoroughly finalized.

Thus, the offensive plan only by the reinforced Austrian army was changed to a joint offensive operation by the Austro-German army. German divisions, aimed at strengthening the Austro-Hungarian army, were deployed through Trentino in order to mislead the Italian intelligence regarding the true direction of the main attack. The Isonian army - 23 divisions and 1800 guns, was reinforced by 14 divisions - German 7 and Austrian 7 with 1000 guns (of which German 800). Finally decided to strike in the area of Pletstso - Tolmino.

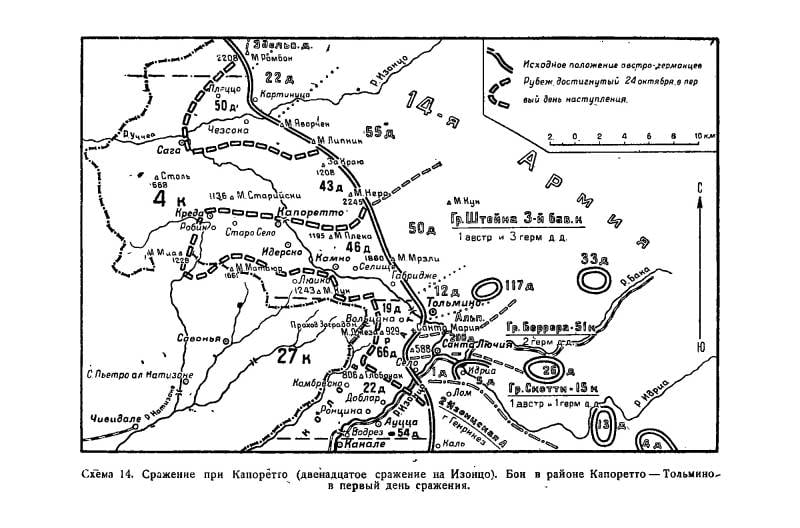

The strike force consisted of the Austrian 8 and 7 German divisions in the 168 battalion - 76 in the first echelon, 63 - in the second and 29 - in reserve. The Italians had a battalion 224 here, but the Austro-German battalions were stronger in composition. The strike group formed the 14 th Austro-German Army under the command of General von Belov. This army was divided into four groups: the Krauss group (3 Austrian divisions deployed on the front from Monte Rombon to Monte Nero), the Stein group (1 Austrian and 3 German divisions, from Monte Nero to Tolmino), the Berrer group (XNUM German divisions, from Tolmino to Idria), Scotty Group (Austrian 2 and German Division 1, Lom Plateau). In addition, the 1 division was in reserve. The army was well equipped with artillery: 4 gun, 1621 mortar and 301 gas guns. From 1000 to 207 guns and mortars located on 259 km of the front, such a density of artillery was the highest in the history of the First World War. The attack of the strike group was supported on the right wing of 1-I Austrian von Krobatin, in the Carnic Alps, on the left-wing - 10-I Austro-Hungarian army, which was part of the Boroevich army group, located in the area of the Bainzitz plateau.

The goal of the offensive was to break through the enemy defenses, entering the Gemon-Cividale line. To do this, it was necessary to completely occupy the area of Plestso - Tolmino and Caporetto. Due to bad weather, the start of the operation was postponed several times, finally, they decided to attack 24 on October 1917 of the year. They decided to launch the offensive not with a lengthy artillery preparation, which gave out the area of the actual attack of the Austro-German assault force, but with a brief and extremely intensive artillery attack. Immediately an infantry attack was to follow. In this operation, they decided to apply the successful experience of the German troops on the Russian front, near Riga (later, in March 1918, on the French front). They used specially formed and prepared assault and assault units, well armed with hand grenades, machine guns, bombers and flamethrowers. As soon as the attack aircraft broke through the front of the enemy defenses, the rest of the infantry, quickly supported by light artillery and machine guns on trucks, quickly moved in between the enemy positions. In the mountainous areas, the offensive was planned to be carried out mainly along the highways, along valleys and mountain passes, without prior capture of the dominant heights, as this caused delays and great losses. Enemy positions on the heights could be taken later, bypassing them and taking a ring. The main goal was to capture the main strongholds and vital centers in the rear, in order to disrupt the enemy’s entire defense system. This technique was completely new on the Italian front, where both armies used to kill time and lose mass during fierce attacks and storming of fortified positions and dominant heights, mountains. These attacks were often fruitless, or the victory was bought at the cost of huge losses, losing precious time, and the enemy managed to tighten up reserves, gain strength in new frontiers and launch a counterattack. The Italians were not ready to attack the assault groups, and this partly explains the first runaway success of the advancing Austro-German forces.

Source: Villari L. The war on the Italian front 1915-1918. M., 1936

Italians

Preparing the enemy offensive was not a secret to the Italian command. Intelligence detected the movement of the enemy troops. The Austrians' closure of the Swiss border 14 September was an important “bell” for the Italians. From the information received from Bern and other sources, the Italians even knew the day the operation began, although at first they did not find out the exact place of the main enemy strike. It was believed that the enemy, apparently, will hit on average during the Isonzo. By October 6, the presence of enemy 43 divisions was clarified; the Bavarian alpine corps and other units were later discovered. The information gathered by the Italian intelligence said that the Austro-German offensive would be launched on 16 - October on 20 on the front from Tolmino to Monte Santo. October 20 to the Italians crossed the Czech officer, who said that the attack will begin October 26 in the area from Pletstso to the sea. October 21 two Romanian defector reported more accurate data: the enemy will go for a breakthrough in the area between Pletstso and Tolmino.

As soon as the Italian command received data on the preparation of an enemy offensive, measures were taken to repel it. The idea of a new Italian offensive was abandoned, efforts focused on repelling an enemy strike. At the edge of the Austro-German strike was the 2-I Italian army under the command of General Capello. The 4 corps was located from Pletstso to Tolmino, with three divisions in the first line (50, 43 and 46), with one division (34) and several Alpine and Bersalier battalions in reserve. The 27 corps stood from Tolmino to Kal on the Beinsitz plateau, with four divisions (19, 66, 22, and 54). The 19 Division was reinforced, almost equal in strength to the hull. In the southern sector of the 2 Army before Wippakko, the 24 Corps, 2 Corps, 6 Corps and 8 Corps (total 11 divisions) held defenses.

Thus, the Capello 2 Army had 9 corps (25 divisions) by force in the 353 battalion (the 231 battalion was in the first line). The area where the enemy was expected to attack was holding the 71 battalion in the first line (50, 43, 46 and 19 divisions), plus the 42 battalion in the second. Against them was the 168 enemy battalions. As a result, the Austro-German troops had some numerical advantage in the breakthrough sector. In addition, the advancing battalions were fully equipped, had in their composition specially trained and trained attack aircraft. And the Italian battalions were incomplete, some soldiers were on vacation or sick. Some regiments had only about a third of the staff. Also, the Austro-German troops had an advantage in artillery.

Another reason for the defeat of the Italian army was, as noted by Hindenburg, the unfortunate location of part of the Italian defensive positions. So, on the front of the 4 of the Italian Corps, located east of the r. Isonzo turned out to be two weak points. In the basin of Plestso, the 50-division had all parts at the bottom of the valley, and because of the location of the groundwater near the surface, the division’s defense area had few closed shelters and buried fortifications. Above the location of the Italian heights commanded by the enemy positions on Mount Rombon and on Yavorchek. A part of the front of the 46 Division passed along the slopes of Mrzli and Voditl, parallel and close to the Austrian positions above, and the terrain behind them steeply descended to the water, so the Italian troops were constantly here not only under the threat of enemy shelling, but also natural troubles - landslides landslides.

The second line was well defended, but it was located close to the first, in some sections the lines almost merged, which made the second line of defense vulnerable. Over the first line of the 27 Corps also commanded enemy heights. The Austrians could flank fire on the forward positions of both Italian corps. In the rear of the 4 and 27 buildings there were two more lines of defense, but they were not prepared in time.

In the first line of defense of the Italian army there were too many troops and artillery (attacking order). Kadorna ordered that only small units, reinforced by machine guns and artillery, be ahead. But his order did not have time to perform. This was due to the fact that almost until the very beginning of the enemy offensive, the Italian command determined its own course of action: pure defense or active defense, offensive-defensive actions. The commander of 2 Army Capello earned a reputation as a hot, brave commander and did not want to accept the idea of a clean defense. He would prefer offensive-defensive actions to passive expectation of an enemy strike, with a strong counterattack on the enemy who had begun the offensive. Commander-in-Chief Cadorna himself was at first inclined to the idea of active defense or "strategic counter-offensive." But then the High Command decided on a clean defense. However, it was too late, the troops did not have time to withdraw in full.

Thus, by October 24, the withdrawal of artillery from the eastern coast of the Isonzo to the western was only partially completed. And when the Austro-German offensive began, many Italian batteries were on the move and could not return fire. As a result, too much heavy artillery was located near the front line when the battle began. There were too many troops ahead - on the Bainzitz plateau and on other sections of the advanced lines. The positions between Plestso and Tolmino were defended by only one corps, although strong. The remaining 8 army corps were located between Bainzitz and the sea. Poor Italian High Command located and reserves, feared strike in the area of Goritsy. From the 114 battalions of the general reserve, which was directly at the disposal of the High Command, the 39 battalions were in the 2 Army, the 60 - 3 Army, and the rest in other sectors.

Thus, the Italians knew about the enemy offensive, knew about the time and the area where the enemy was attacking. But the Italians assumed that the offensive would be with limited goals - to recapture previously lost positions. Indeed, most of the Austrian and German generals themselves did not expect that the Italian defense would collapse and that they would be able to advance so far.

To be continued ...

Information