On the way to the assault rifle

It is believed that the term “Assault phase rifle” was first used by Isaac Lewis, an American designer and creator of the famous machine gun of the same name, applied to the line of experienced automatic rifles he developed in 1918-1920. These rifles used regular American rifle cartridge .30 M1906 (.30-06, 7,62х63 mm). It should be noted that the German 7,92x57 mm cartridge with a light pointed bullet had a great influence on the development of this cartridge. Impressed by the success of engineers from Germany, their American counterparts in March 1906 began work on their rifle cartridge with a pointed bullet. Experienced Lewis automatic rifles repeated the same concept of "firing on the move" as the Browning BAR M1918 automatic rifle.

The people who came up with this concept were the French. At the beginning of the 20th century, the French army was at the height of technical progress. At first, self-loading rifles were adopted here, and during the First World War, infantry were equipped with a new class of small arms — automatic rifles, which were mass-produced in France. Thanks to this, the French infantry received weapons suitable for firing from the belt from the hands or from the shoulder, from short stops or on the move. The main purpose of the French automatic rifles was to support infantry, which was armed with ordinary magazine rifles, directly during the attack or assault of enemy positions.

The first production model of a weapon of this class is called a machine gun, an automatic gun or a Shosh machine gun of the 1915 model of the year (Fusil Mitrailleur CSRG Mle.1915). Soon after it, the famous Fedorov automatic rifle of the 1916 model of the year was created in Russia later; history like an automatic machine Fedorov. Finally, in 1918, in the USA, Browning created his M1918 automatic rifle.

The first swallow of hand-held automatic weapons, which, of course, was the model Fusil Mitrailleur CSRG Mle.1915, was originally designed taking into account the possible mass production at non-specialized enterprises (the Gladiator bicycle factory was the main manufacturer of this machine gun during the First World War). The weapon managed to become really massive, in just three years of the war more than 250 thousands of units of this machine-gun were assembled. At the same time, mass production became the model’s weakness and its weakest point — the level of industry at the beginning of the 20th century did not guarantee the required stability of characteristics and quality from sample to sample, which, combined with a rather complex weapon design and a magazine to increased sensitivity of the model, to the general low reliability and sensitivity to pollution. At the same time, with proper maintenance and proper maintenance, the CSRG Mle.1915 light machine gun could provide acceptable combat effectiveness (they tried to recruit shooters from non-sergeants, and their training lasted up to three months).

A characteristic detail of this model was a huge open-type sector magazine, which was designed for just 20 unitary rifle cartridges Lebel 8x50. In many ways, it was the unsuccessful design of the store that was the main source of claims to the weapon. Many called the Shosh machine gun the worst weapon in its class, prone to a very large number of failures and delays when shooting. Other drawbacks of the weapons were very high recoil and low rate of fire - just about 250 shots per minute.

Both the French Fusil Mitrailleur CSRG Mle.1915 and the Fedorov machine gun and the Browning M1918 combined the fact that all three "assault rifles" had one drawback - they used regular rifle cartridges from that time period, which had a frankly excessive range for the assault use and firing range. All this led to a very strong impact when fired, as well as a significant mass and dimensions of the weapon itself. The fact is that the rifle cartridges of those years were created in the late XIX, early XX century, when salvo firing from long-range rifles was considered the normal and generally accepted method of infantry combat. As a result, the deadly range of rifle bullets of those years reached two kilometers, whereas in a real battle the infantryman could hardly expect to see enemy fighters more than 300-400 meters away, not to mention getting into them high probability. At the same time, none of the military denied the importance and necessity of maneuverable automatic fire in order to suppress the resistance of the enemy both during the attack and in defense.

An obvious solution to the emerging problem could be the creation of new cartridges with reduced power. Such ammunition would solve the problem of defeating enemy soldiers at a distance of 300-500 meters. Moreover, the development of such cartridges promised a serious gain in their mass, and hence in the mass of weapons in general, as well as in reducing recoil when fired, in saving gunpowder and materials, in increasing the number of cartridges worn by the soldier.

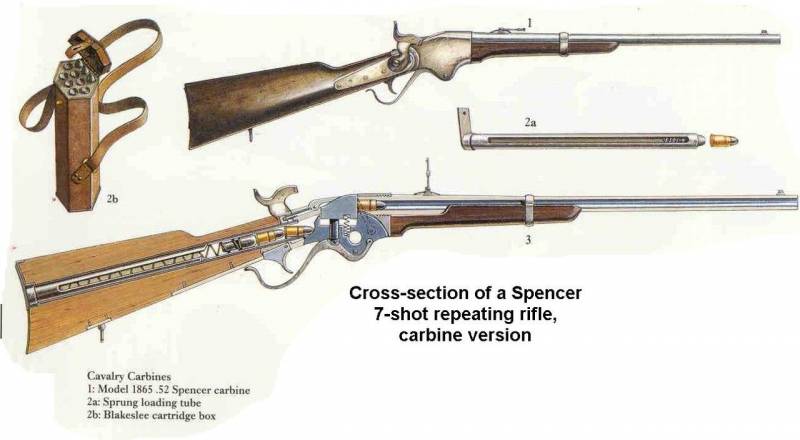

Curious is the fact that the very concept of “weakened” rifle cartridges appeared during the domination of black powder — a number of armies in the second half of the 19th century armed their cavalry units and other non-infantry units with carbines that fired weakened (compared to regular rifle) cartridges . At this stage, the closest to the implementation of the concept of "assault rifle" were the Americans, who created and produced the high-speed shop carbines of Spencer and Henry systems. These carbines were actively and successfully used during the American Civil War, and then used during the conquest of the "Wild West". These were compact and lightweight models of small arms, which used significantly weaker cartridges than ordinary single-shot army rifles of that period. This was more than compensated for by a significantly higher density of fire in the short range, which was especially important during cavalry attacks, which were quite transient. The same rifle and Spencer carbine were equipped with a tubular magazine for 7 cartridges, all 7 bullets could be fired at the enemy in 7 seconds, for that time it was a fantastic rate of fire.

Started in 1914, the First World War gave the warring parties real combat experience in using such small arms. For example, in 1917-1918, the French infantry successfully used Winchester 1907 self-loading American carbines chambered for .351 WSL (9x35SR). They were equipped with high-capacity stores and redesigned for the possibility of firing bursts. The Winchester 1907 carbines were much more comfortable and shorter than conventional rifles of those years. They provided soldiers with greater freedom of maneuver and were equipped with boxed magazines on 5, 10 or 15 cartridges, and could be effectively used at a distance of up to 300 meters. The model of this 1917 rifle of the year has been specially modified to enable bursts of fire, and also received a new magazine designed for 20 cartridges. The shooting rate of the 1907 / 17 model was on the order of 600-700 rounds per minute. In fact, the Winchester 1907 was a harbinger of a new class of small arms - automatic carbines for reduced power rifle cartridges, also called “intermediate” (the average between conventional rifle and pistol cartridges).

Already in 1918, in France, on the basis of the hunting cartridge .351WSL, a special army cartridge 8x35SR was developed, which was equipped with a pointed bullet from the French 8-mm cartridge Lebel. An experienced automatic rifle Ribeyrolles Modele 1918 (the official name is Carabine Mitrailleuse 1918) was developed under the designer cartridge Ribeirol. Since the 8X35 mm cartridge is close in its characteristics to the intermediate cartridges, this gives grounds to consider the Ribeirol carbine to be one of the first predecessors of the modern machine gun.

In the same year in the United States, Winchester also created a similar cartridge. Taking the sleeve from the .351WSL as a base, American engineers supplied it with a 9-mm pointed bullet, the new cartridge received the designation .345WMR (Winchester Machine Rifle), its initial velocity of the bullet was approximately 560 m / s. Especially for this cartridge, a Burton-Winchester Machine Rifle automatic carbine system, quite original in design, was created.

It was a free-gate weapon, the original features of the model were interchangeable barrels (ordinary for the aviation version and shortened with a tide for the bayonet, intended for infantrymen), as well as an unusual system of feeding cartridges. It included two receivers for sector stores, they were located on top of a weapon in the shape of a letter V. The stores had a capacity for 40 cartridges, and the switching of weapons to the second store took place automatically after the first one became empty. The rate of fire was already on the order of 800 shots per minute, while providing a fairly good practical rate of fire. The weight of the carbine was about 4,5 kg without cartridges.

Later in the beginning of the 1920-s, similar cartridges and automatic or self-loading carbines for them were developed in Italy and Switzerland, in the 1930-s - in Germany and Denmark. However, none of these models were eventually adopted. So why so promising, it would seem, small arms did not receive widespread use until the second half of World War II, here are just a few assumptions on this subject:

1. High-ranking military men were conservative in their nature, not risking their careers in the name of development, whose usefulness was not completely obvious to them. Most of the warlords of that time grew up in the conditions of the wide use of magazine rifles with a magazine cut-off, bayonet attacks and salvo firing. The idea of arming the fighters with high-speed automatic weapons on a massive scale seemed alien to them.

2. Despite the obvious savings in production costs, materials and delivery of each cartridge, a significantly increasing consumption of ammunition in automatic weapons compared to ordinary magazine rifles would still lead to an increase in the level of load on both production and logistics.

3. By the time of the end of World War I, light and heavy machine guns had become an integral part of infantry weapons. Therefore, the use of significantly weakened intermediate cartridges in machine guns, especially heavy machine guns, would mean a sharp loss in the effectiveness of their fire on all types of targets, and this in turn meant the need to introduce a new weakened cartridge in parallel with the release of traditional rifle cartridges (and not in their place) that also only complicated the logistics.

4. Up until the end of the 1930, not only enemy soldiers but also horses (in many countries, cavalry was still a very important type of force), as well as armored cars and low-flying aircraft, were among the most typical targets for infantrymen to hit with small-arms fire. The use of weakened "intermediate" cartridges could seriously reduce the ability of infantry units to combat these objectives, which was considered unacceptable.

Of course, there were other reasons, as a result, in the pre-war period in most countries of the world, self-loading rifles designed for “traditional” rifle cartridges were considered as promising individual infantry weapons. Attempts of adopting reduced-power cartridges for self-loading rifles or creating automatic rifles for regular rifle cartridges (German FG-42 and Soviet ABC-36 under 7.62х54R) were unsuccessful. As a result, by the beginning of World War II, most of the infantrymen of all the howling countries were still armed with self-loading rifles or store rifles with manual reload, designed for long-range and powerful rifle cartridges.

Information sources:

https://www.all4shooters.com/ru/strelba/tekhnika/Shturmovyye-vintovki-1-zadolgo-do-Shturmgevera/

http://modernfirearms.net/machine/fr/chauchat-csrg-m1915-r.html

http://www.armoury-online.ru/articles/civil/us/win-1907

Open source materials

Information