Small fortress against a large fleet. Defense of bomarsund

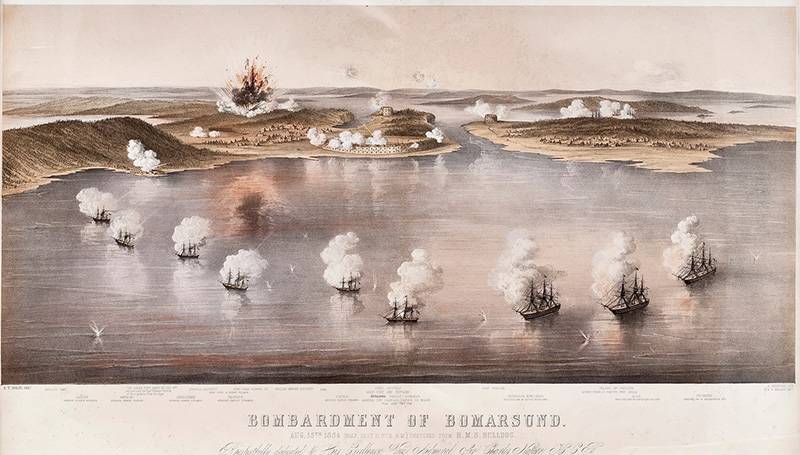

By the evening of August 14 1854, the fire of the Allied siege artillery did not drop - there was plenty of ammunition, and the proximity of success gave hunting excitement. Explosive mortar bombs fell in abundance not only in the long-suffering tower "C", but also in the main fort of the Russian fortress Bomarsund. The commandant of the tower, Captain Tesche, who had literally a handful of completely exhausted and most of the wounded people on hand, was aware of the current, almost hopeless situation of both the fortifications entrusted to him and the entire fortress. However, according to the testimony, stingy to the enemy’s praise and the BritishStories Baltic campaign ", the garrison courageously defended its position, and its artillery worked without stopping.

Already at dusk, the French huntsmen leading a tight fire on Russian positions noticed how a parliamentary flag appeared in one of the embrasures. The commander of the French expeditionary corps, General Barage d'Hillet, and several officers approached the walls of the C tower to find out the intentions of the besieged, secretly hoping that the Russians would capitulate. However, his hopes did not come true. Captain Teshe requested only a four-hour truce - he had many wounded who needed help. Some of them were going to ship to the main fort, under more reliable protection. However, the general, finding that in four hours a few defenders of the tower "C" will receive reinforcements and ammunition, agreed only to a cease-fire for a period of not more than an hour. Sources of allies give different answers to the defenders of the tower "C". The French claimed that the Russians had rudely advised Barage d'Hillet to get out, for they would resume the fire now. The British, however, claim that their enemy only urged the French envoys to hasten. One way or another, but the bombing of the tower “C” was resumed - she met her last night. Bomarsund still held out.

Old nodules of the next international tangle

For Europe, peace by the middle of the 19th century was still unattainable. Naive romantics and dreamers still spent the evening at the fireplaces, talking about the era of universal peace and prosperity, which for some reason was in no hurry to attack. The grandiose and tragic era of the Napoleonic wars died down and scattered in powder shroud. Swept by a raging stream, shaking gray and dust covered thrones, the wave of revolutions of the forties. But after a series of military-political storms, the much-expected calm did not come. And in Europe, the smell again habitually to the pain - gunpowder and iron.

The winners of the famous prisoner of Saint Helena made different conclusions after the completion of the pompous and optimistic-looking, but not the content of the Congress of Vienna. Emperor Alexander placed too much hope on the created Holy Alliance with Austria and Prussia, believing that this alliance would become the most effective preservative of post-Napoleonic Europe. Practical as the British were absolutely opposed to any unions without their participation. Strengthening the role of Russia in European affairs, the United Kingdom considered completely unacceptable. The relationship between the two monarchies remained very difficult for all three decades between the battle of Waterloo and the Sinop battle.

Nicholas I, who succeeded his elder brother on the throne, was much less inclined to idealize relations with European “partners,” but Russia continued to move in the wake of the Vienna Congress. In matters of the Middle East policy, the Greek problem, St. Petersburg tried to coordinate its actions with London and Paris. During the Hungarian uprising in Austria, Russian troops directly supported the wandering monarchy of Franz Joseph. However, England and France saw in the Russian Empire only a hostile rival, whose ambitions needed to be shortened and pointed to its proper place. Traditional diplomatic sclerosis and Vienna, confidently embarked on the path of hostile neutrality.

The central and intricately knotted knot of contradictions and intractable problems remained the increasingly decrepit Ottoman Empire. The days of her greatness have long been the subject of gossip in Istanbul coffee houses, heavy sighs and nostalgic memories. In no case could Britain allow Russia to finally reach its long-established geopolitical goal: to gain control over the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles. Turkey itself has weakened from year to year. The recent war of 1828 – 1829. only showed all the tragedy of the position of the old and sick empire.

Heavy civil strife with the ruler of Egypt Muhammad Ali almost caused the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The collapse of Turkey was prevented only by the intervention of Russia and a number of European states. In July, 1841 was forced to ratify the London Straits Convention, according to which Russia could no longer block the entrance of third-party ships in the event of war. This item will hurt to respond later. However, the Turks were no longer fit for the role of the dam, which was independently restraining the pressure of St. Petersburg, but Britain herself did not want to fight for the territorial integrity of Turkey alone. This contradicted her political principles.

And then the English expectedly lucky - in France, in the wake of Bonapartist revanchism and the state crisis, the evil nephew of Bonny, Louis Napoleon, came to power. Uncle glory did not give him rest, and very soon the presidential chair was replaced by the pompous throne of Emperor Napoleon III, whose pointed beard, like a compass needle, increasingly pointed to the East. The fact that in the congratulatory letter Nicholas I called Louis Napoleon his “friend” and not “my brother” relying, was perceived in Paris as an insult. The situation was tense - the Western partners, who had forgotten their eternal offenses and contradictions, were ready, in addition to caustic diplomatic notes and statements, to use even more acute weapon.

The conflict between the Orthodox and Catholic missions in Palestine over the ownership of the keys to the Church of the Nativity of Christ in Bethlehem broke out. There were more than ten million Orthodox in the Ottoman Empire, while Catholics numbered tens of thousands. The main arbiter in the outbreak of the conflict was the Turkish Sultan - Palestine belonged to him at that time. In the end, after long disputes, control over the Church of the Nativity of Christ was transferred to the Catholics, which clearly meant the success of not only the Vatican, but also Napoleon III, who considered himself the patron saint of Catholicism.

Wanting to return to the position, Nicholas I, who mistakenly believed that England and France would not agree, and even more erroneously counted on the help of Austria and Prussia, sent his personal representative of Prince Menshikov to Istanbul with a solid retinue. The false and dramatic diplomatic game that followed — the Vienna Note of England, France, Prussia, and Austria — the entry of Russian troops into Moldavia and Wallachia requires a separate article because of the vastness of the material. As a result, Menshikov left with nothing, the Turkish sultan Abdul-Mejid I, incited by the British ambassador in Constantinople, Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, on October 4, 1853, declared war on Russia.

The return move followed on October 20 in the form of a royal manifesto. The calculation of Nicholas I on internal contradictions between Western countries did not materialize. When it comes to the issue of causing this or that harm to Russia, the Western "partners" show surprising unanimity. In November 1853, Admiral Nakhimov inflicted a crushing defeat on the Turkish side. the fleet in the battle of Sinop. In response, as if on command, the democratic press of all calibers raised a heartbreaking howl about the “massacre” perpetrated by the Russians. By the way, full of humanity and exclusively peaceful intentions, the fully mobilized Anglo-French fleet entered the Sea of Marmara in early November.

Further developments developed incrementally: at first, England and France broke off diplomatic relations with Russia, and on March 15 London declared war on “a barbarous nation, the enemy of any progress” (as the Honorable Lord Lyndhurst expressed a member of the House of Lords). 16 March has finally exposed his uncle's sword and Louis Napoleon. The British "Times", far from sentimentality, pragmatically stated that "the goals of the war will not be achieved as long as Sevastopol and the Russian fleet exist." To the greater chagrin of the lords of the Admiralty, Russia had a fleet not only on the Black Sea.

Away from the Sinop volleys

The fleet of the Russian Empire was rightly considered one of the strongest in the world and by the beginning of the Crimean Empire, or, as they began to be called in the West, the Eastern War firmly held third place after the naval forces of England and France. The largest naval compound, of course, was the Baltic Fleet, which at the beginning of the war had 23 sailing battleships, 12 steamboat frigates, 11 sailing frigates and some smaller rank ships. The main naval base was well-fortified Kronstadt. Admiral Charles Napier, commander of the British fleet in the Baltic Sea, who visited him after the war, was forced to admit that the forts of this fortress were so strong that it was almost impossible to take it from the sea. There were also a number of other major naval fortresses, among which Sveaborg stood out.

Knowing about the superiority of the allies at sea, the Russian command did not at all rule out an attempt to attack not only Kronstadt, but even St. Petersburg. True, the most sober-minded, like Prince Golitsyn, Adjutant General Admiral Konstantin Nikolayevich’s adjutant, rightly pointed out the impossibility of such a threat to the Russian capital. Rather, in his opinion, expressed in a memorandum, one should have expected the destruction of Russian maritime trade and individual tactical landings with limited objectives.

Views on the use of the Baltic Fleet in the outbreak of the war were very different - reports were laid on the table of the head of the marine department of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich with enviable regularity. Their tone and content were also quite varied: from the bold, “capturing” doctrines of Vice-Admiral Melikov (who didn’t touch the fleet from the 1832 of the year, however) to the strictly defensive concept of Adjutant General Litke, a teacher of Konstantin Nikolaevich himself.

The outcome of the disputes was summed up in March 1854 at a large meeting with the Grand Duke. It was decided in view of the substantial technical superiority of the enemy to adopt defensive tactics. The fleet was supposed to be kept in the well-fortified harbors of Sveaborg and Kronstadt, waiting for the attack of the enemy. The final resolution of the meeting emphasized that if the Allies left the Baltic without achieving any success, this would be tantamount to a lost battle. It is quite possible to admit that gentlemen admirals calmed themselves a little. The Baltic Fleet, which in peacetime took so much manpower and resources, and which had glorious military traditions and history, was to play a very modest role.

Allies go to the Baltic

If in regard to the Black Sea and Sevastopol, which Western newspapermen have already begun to level with the land, to burn and plunge into abyss in every possible way with the hated Russian fleet, the Western allies had more or less common views, then there was no similar unanimity regarding the Baltic. The emperor Louis Napoleon saw in the upcoming activity in this theater an exclusively political factor. The successes of England and France, in his opinion, could, first, ignite a long-burning fire in the Kingdom of Poland, where the tension was becoming almost chronic for the Russian authorities. Secondly, the emperor was well aware of the revanchist sentiments in the military and political circles of Sweden, which could not forgive her neighbor for the loss of Finland in the early nineteenth century. Militantly correct steps could have endorsed this kingdom unfriendly to Russia to join the coalition, join the war and form a new theater of military operations.

The British, unlike their allies, did not build such large-scale plans - they were determined to undermine the sea power of their enemy in the face of the Baltic Fleet and to nullify the Russian sea trade. At the end of winter, the 1854 on the Spithead raid began to form a British squadron to march on the Baltic. Charges were difficult and accompanied by some red tape. Since all the best, including officers, sailors and ships, was primarily selected and sent to the Black Sea, which was considered the priority theater of war, the Baltic squadron was formed from the pine forest. The command on it was assigned to Vice-Admiral Sir Charles John Napier, who had the reputation of a bold, determined and energetic seaman and commander, who was, however, in a very strained relationship with the Admiralty.

For operations on the Baltic, 10 propeller and 7 sailing battleships, 22 steam frigates and corvette and a number of smaller ships were allocated. The personnel of the squadron, from the words of Napier himself, was recruited from the "scum". There was a shortage of pilots, lacked a variety of equipment and equipment. At the same time, the command and the hunt for sensational society demanded from the admiral a speedy departure and equally quick and loud victories.

The French were also eager to take part in the upcoming expedition, although the capabilities of the French fleet were weaker than that of an ally, most of which went to the Black Sea. Nonetheless, Louis Napoleon ordered his own squadron to be prepared for shipment to the Baltic Sea, which included the newest 100-gun steam warship Austerlitz, 8 sailing battleships, 7 sailing frigates and 7 smaller steam ships. The command was carried out by Vice-Admiral Parceval-Deschen. On the ships of his squadron were 4 thousands of paratroopers. However, the French were ready to send a special expeditionary force to the Baltic, but its preparation was delayed.

Meanwhile, Charles Napier, bending down in every way and lords, and frankly bored the public, left England and moved to the Baltic. An official declaration of war has not yet followed, but this was a long-resolved issue. 7 March British squadron reached Denmark. Further, the pace of advancement of Sir Napier was significantly reduced - the Danish pilots categorically refused to conduct British ships through their waters, citing neutrality. The king of Denmark, to whom the British commander was about to make a visit, “fell ill” on an emergency basis.

On March 12, the British arrived in Kiel, and the 20s anchored in Kyoga Bay on the island of Zealand, where they received information about the beginning of the war with Russia. The English public rejoiced - still, the first success! Napier, they say, was ahead of the Russian fleet and was the first in the Danish straits. Even the Admiralty condescended to approval. No one in England yet knew about the defense strategy adopted by the Russians, and that their ships were protected by the forts of Kronstadt and Sveaborg.

Receiving reports from the steamer Miranda that the Gulf of Finland is covered with ice, Napier took up intense combat training, first and foremost, shooting. The lords of the Admiralty, on the one hand, demanded from the admiral "victories and accomplishments", and on the other, they filled him with a stream of instructions and recommendations, often contradicting one another. In general, the leadership of the Baltic expedition was more concentrated in London (from which it could be seen better) than in the admiral cabin of the British flagship.

To find out the location of the Russian forces, 5 high-speed steam-frigates under the command of Rear Admiral Plumridge were sent to the Gulf of Finland. Meanwhile, 25 in March, the French battleship Austerlitz arrived at Kyogue Bay at full speed and reported that the rest of the squadron, almost the entire sailing ship, had not yet left Brest. Plumridge, who returned from intelligence, reported on the 7 Russian battleships and frigate in Sveaborg. Understanding that further delay may be misunderstood in London, seeing everything from across the sea, 31 in March Napier left Kyoke Bay and moved east.

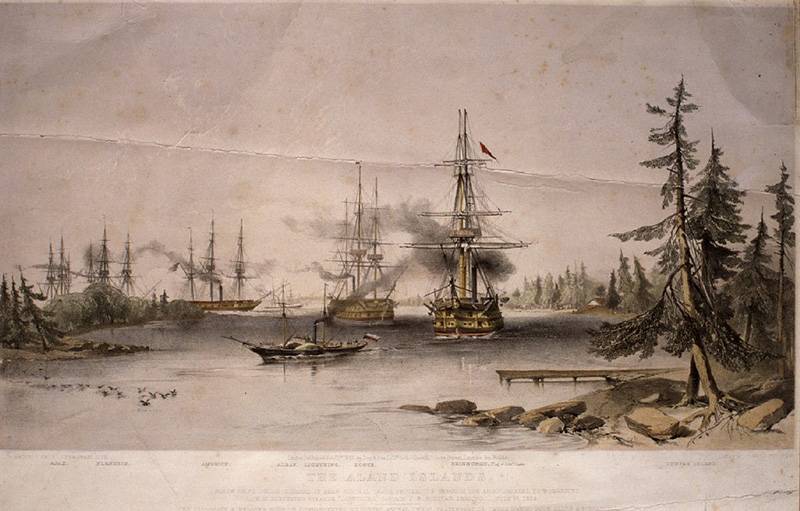

The Allies moved very carefully, because they had only the most general ideas about the navigation features of the local waters. In his regular reports to the Admiralty, Napier often complained about the lack of pilots. Reaching the Gulf of Finland, the Allies landed in a storm, and further being in enemy waters was considered dangerous. Napier anchored in the Swedish bay of Elksnabbene near Stockholm. Correcting the damage and continuing to train the teams that were too inexperienced, the admiral stayed here for two weeks, and in early May he moved to the Gangutsky raid. Here it was decided to wait for the French squadron dragged from Brest while at the same time carrying out intensive measurements of the depths on the approaches to Sveaborg and the Aland Islands. At the end of May, Vice Admiral Parseval-Deschene finally joined the British, and the obvious question was what to do. Louis Napoleon, by the way, was so eager to render allied aid that Parseval-Deschene was forced to leave Brest with incomplete crews and with insufficient reserves.

The intensive cruising of the Plumridge frigates in the Gulf of Bothnia did not bring glory to the British fleet, and the destruction of coastal towns and villages only embittered the local population. The inspection of Sveaborg undertaken by the British gave Napier a reason to compare it with Gibraltar in a letter to the Admiralty and point out that it was impossible to take this stronghold without a large flotilla of gunboats and a significant landing corps. Going to Kronstadt was even more dangerous. Having stood at anchor near the main Russian base from 14 to 20 in June, the allies left with nothing.

But the mere evolution of the Anglo-French fleet and the demonstration of flags could not satisfy the monarchs who craved for high-profile events, the command and the public of England and France. We needed at least some victory, exceeding in scale the ruin of defenseless Finnish villages. And here the Admiralty came to the aid of the admirals, generating ideas, guidelines and recommendations. Napier clearly pointed out the Aland Islands and the small Russian fortress Bomarsund located on them, whose fortifications, to the delight of the allies, could not be compared with the power of Sweaborg and Kronstadt. In addition, both in England and in France, they were confident that in the case of the transfer to the Swedes of the archipelago that had been beaten off from the Russians, Stockholm would join the coalition from happiness.

Small fortress against large fleet

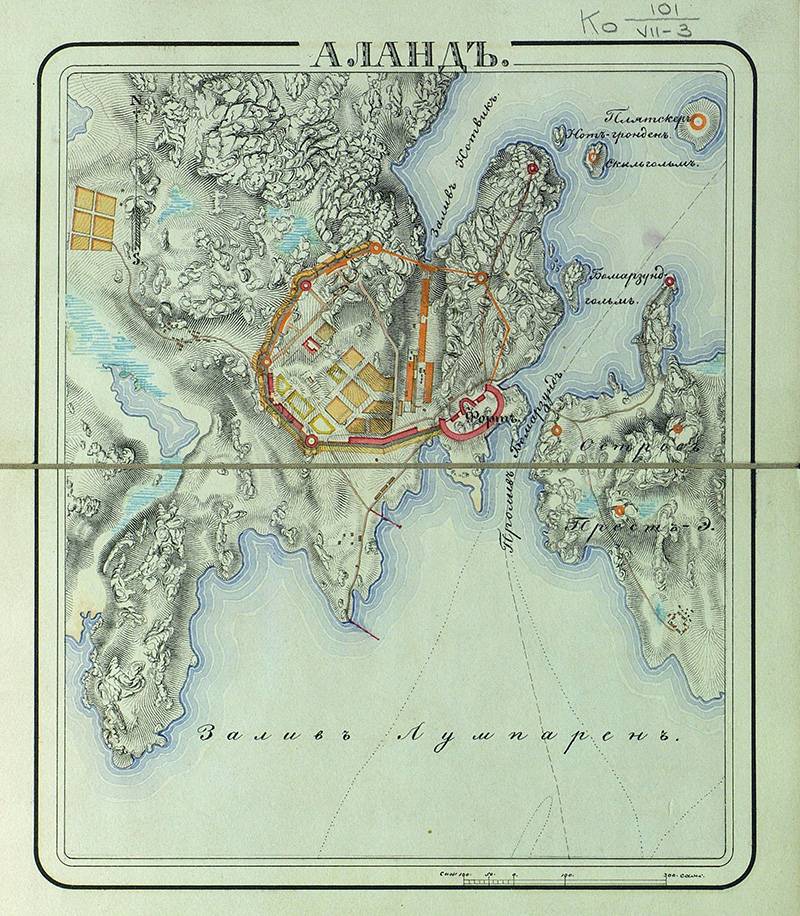

The fortifications described on the Åland Islands were far from being perfect, but also defensive sufficiency. Conceived back in 20-s. XIX century to counter Sweden in a possible war, by the beginning of 1854, they were ready by almost a quarter. On the main island of the Aland archipelago, a fort was built, representing a two-story stone defensive barracks with more than 2 thousand people and having embrasures 115. In addition, three stone towers were built. The two were located on the same island as the fort — they provided protection for the main fort from the west and north. The third tower was on the island of Prest-e and was intended, like the fort, to bombard the Bomarsund Strait.

On the eve of the war, 139 guns were delivered to Bomarsund, of which 66 were placed in the main fort and 44 in the towers. The rest, in the absence of gun carriages, continued to lie in the fortress courtyard. The garrison of the fortress consisted of 42 officers and 1942 soldiers, some of whom were Finns by nationality and came from local ones. The fortress also had a number of prisoners and penalty box. The command was carried out by 60-year-old Colonel Yakov Andreevich Bodisko, who was not distinguished by special military talents, but showed diligence in service. Bodisko received a special instruction, which indicated that the Bomarsund fortress could be attacked only by the fleet, so you should focus on the defense of the fortifications. Based on this erroneous concept, the Bomarsund garrison at the start of the war was not reinforced by reinforcements. However, the belated decision to send 40 gunboats there and several small steamboats was made only in July, when the connection with the Aland archipelago was already interrupted.

Another 9 June 1854, a detachment of British steamboats and frigates made a primary reconnaissance of Bomarsund, entering into a shootout with the newly built coastal battery 4-gun, which was suppressed. The defenders of the fortress also managed to achieve several hits on British ships, causing a fire on one of them. The last who was able to deliver information about the position of the fortress to Russia was the adjutant of the Minister of War, Captain Shenshin, who distributed awards to those distinguished during the bombardment of June 9. Disguised as a fisherman, he managed to get to Sweden, and from there to arrive in Russia. The allies had already blocked the Bomarsund by then.

18 July 1854 another event happened - the French assault force finally arrived in the Baltics under the command of General Barague d'Hilles, who had previously been the representative of France in Istanbul. Barage d'Ille was in a difficult relationship with his English counterpart, Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, besides, there was no place for him among the high command of the expeditionary army. Wanting to amuse the self-esteem of the old general, they set him up to command the airborne detachment in the Baltic.

Bomarsund was already completely blocked from the sea - the garrison soldiers could clearly observe the actions of the English steamers that did not respond to the fire of the fortress. By this time, the insufficient range of serf guns had already been noted. On the night of 26 on 27 July, the defenders of Bomarsund heard a loud cannon firing - these are the British ships of Napier blocking the archipelago, saluting to their French allies. Under the escort of the squadron Parseval-Desheny, the first transports with Barage d'Iliers soldiers approached the scene. By the indescribable indignation of Napier, the general did not jump from ship to shore with a naked saber, but began to expect all the other transports with troops to arrive, some of which were stuck in Kiel. The Englishman wrote letters full of curiosity to his homeland, where he scolded the slow-moving Frenchmen, who would end up with the landing until the very winter.

The onslaught of Napier, the thirst for military glory and the whipping of the higher command eventually did their job, and on August 2 1854, the first companies of French paratroopers began to disembark in 12 versts from the main fort. Serviceman Bodisko, who, after the bombing of 9 on June, was promoted to general, clearly realizing that from this point on, all instructions for defending the fortress only against the encroachment of the enemy fleet can be used for a certain purpose, he gave the order to destroy all buildings beyond the perimeter of the Bomarsund defense.

During 2, 3 and 4 of August, food shops, a garrison artillery stable, a bathhouse and a guardhouse were burnt down. 7 August the landing of the main forces of the allies began in the morning at 3. Soon there were more than 11 thousand people on the coast: the French landing corps and a small detachment of British sailors. The 8, 9 and 10 of August were unloading siege artillery, ammunition and provisions. Barage d'Ille decided to hedge, soon reinforcing the already considerable forces for the task 2 by thousands of French sailors. Already on August 7, fire was opened on the fortress, and in the morning 8 numbers of the French approached her at close range. The purpose of the initial attack was the so-called tower "C", which dominates the surrounding area. Commanded by the defenders of the tower engineering captain Teshe, who had at his disposal only 123 man: fighters of the Finnish and Grenadier battalions and gunners.

The besiegers quickly erected three siege batteries against the tower, which immediately opened heavy fire on it. Reciprocal shooting of the Russian artillery was ineffective, since the cores simply did not reach the target. The French in such a situation acted as on the range, slowly and confidently taking aim. Defenders who did not lose morale expected the assault, but the enemy, taking advantage of his advantage, was in no hurry with this troublesome and costly affair. Not only the “C” tower, but also the main fort of the fortress itself was subjected to intensive bombardment. The return fire of the Russian artillery was intense, but ineffective.

On August 9, the Penelope steamer ran aground in the sight of the fort, and heavy fire immediately opened fire on it. The enemy ship received at least ten hits, however, it was freely removed from the ground by another English steamer. 13 August position of the defenders of the tower "C" has become critical. Under the cover of artillery fire, French huntsmen approached and showered the embrasures with bullets. The fire of Finnish snipers, so effective in the early days of the defense, was neutralized by almost constant shelling of explosive bombs.

Captain Teshe kept in touch with the fort all these days, from where supplies and ammunition were delivered to his subordinates. The few remaining guns in the tower continued to fire. By the evening of August 13, the Russians offered a truce for an hour of 4, in order to transport the wounded to the main fort. However, self-confident Barage d'Hillet agreed only to an hour-long cease-fire. In response, the French parliamentarians politely, and perhaps not very much asked to retire. The bombardment resumed with a new force.

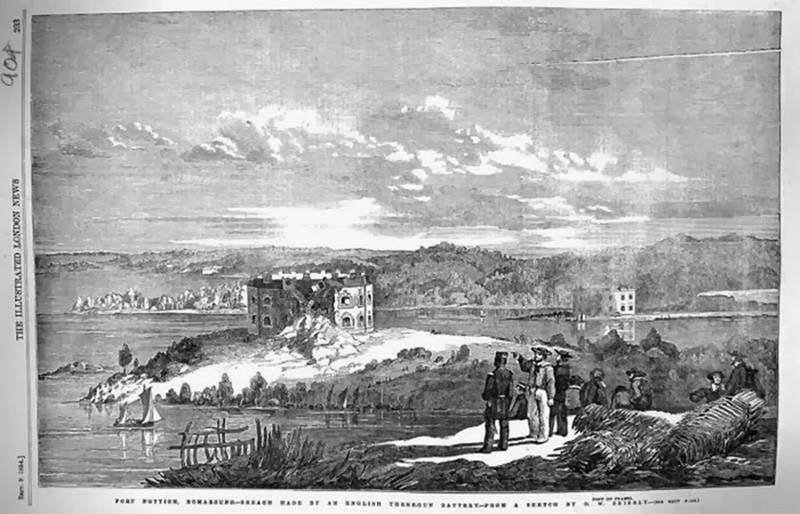

By nightfall, the few Russian artillery of the already pretty destroyed tower “C” was left without nuclei, and the position of its defenders became critical. Captain Tesche ordered the guns to be riveted and retreated into the fortress. Parts of the garrison in the dark succeeded, and Teshe himself, seriously wounded, and the few soldiers who remained with him were captured in the morning of August 14. A new battery was immediately erected on the territory of the captured tower “C”, which began to fire directly on the main fort. However, the lieutenant colonel of the Finnish regiment Kinstedt returned fire from three mortars and achieved an explosion of the powder cellar on the enemy's battery, silencing it.

Then Barage d'Ille called for help the fleet. Already in the morning of August 15, on the day of Napoleon's idolatry, the 8 battleships beat the fortress, helping the already not small siege artillery. The Russians continued to fight - prisoners stood up in line with the soldiers of the garrison. They were equipped with the calculations of three mortars, suppressed the French battery. Moreover, according to eyewitnesses, they showed desperate courage. When, on the orders of Bodisko, external structures were burned, among them was the prison. His guests were transferred to the fortress, and now they have become its defenders.

But the advantage of the enemy was overwhelming. The Allied fire intensified - all new ships joined the eight battleships. One by one, the Russian batteries became silent, their cores did not reach the enemy. Bodisko gathered a council of war, at which it was decided to stop the resistance. At one o'clock in the afternoon of August 16 1854, a white flag was hoisted over Beaumarsund. General Barage d'Hillier, who entered the fortress, in order to respect the courage of the Russians, ordered the officers to leave their personal weapons. He also thanked Bodisko for prudence, because, according to him, in the event of an assault, angry with the stubborn defense of the fortress, the French would not have taken prisoners. The garrison lost 53 people killed and more than a hundred wounded during the siege. Allied losses were doubled. Blowing up and disabling all the remaining fortifications, the winners soon left the Aland Islands. Sweden did not dare to demand from the allies a delicious, but potentially fatal gingerbread.

Throughout the war, Bodisko spent in captivity with his family - his wife and children, who had the opportunity to go to Russia, stayed with him in Le Havre. The capture of the small fortress of Bomarsund was the only success of the Allies in the Baltic Sea, although the press, eager for sensations, in vain exhibited this tactical success as a grand victory. The Marshal's baton Barage d'Hillet, who received the victory, was soon forced to return to France - cholera brutally mowed his paratroopers.

The fate of the war has not yet been resolved, the bastions of Sevastopol, Admiral Nakhimov, the sailor Koshka, Dasha of Sevastopol and thousands of its defenders were still waiting for their time.

Information