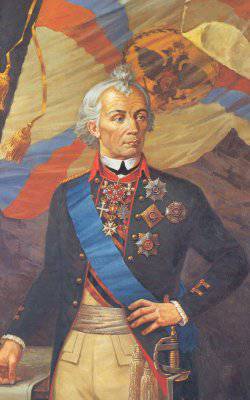

Epole Massena

History, what happened here, is still interpreted from the point of view of opposite sides in different ways. Some are convinced that the actions of the Russian troops, led by Suvorov, were his fatal mistake. Others - that they were the only true ones and, under the best of circumstances, could alter the further course of history.

One way or another, but what happened happened, everyone is free to draw conclusions himself. In the meantime, try to understand what happened in the Alps at the very end of the XVIII century?

In 1789, France from a centuries-old, established and influential monarchy turns into a republic that has barely emerged and longed for freedom. Sensing the growing danger, the European monarchs yards began to unite their efforts in trying to pacify rebellious France. The first of the military alliances created against it, in which Austria, Prussia and Great Britain entered 1792, failed to bring any results, it broke up after 5 years. But less than a year later, Austria, Great Britain, Turkey, the Kingdom of both Sicilies, as well as Russia that joined them in 1798, formed the second anti-French coalition even more concerned with the current situation. At the same time, the French army, led by the young General Bonaparte, had already invaded Egypt, capturing the Ionian Islands and the island of Malta, which had great strategic importance.

The Russian squadron under the command of Admiral Ushakov approached the Ionian Islands and blocked the island of Corfu, which was the key to the entire Adriatic. The attack of the island’s fortified fortress from the sea forced the French garrison to surrender 2 March 1799. On land, the Austrians, having an army twice as large as the French, managed to push General Jourdan’s army back beyond the Rhine, but suffered a serious defeat on the border with Tyrol. Coalition got into a very difficult position.

At the urgent request of the allies, Field Marshal A.V. was to lead the combined forces in order to save the situation. Suvorov. He, who was discharged from service because of his disagreement with Emperor Paul I about the reforms he was conducting in the army, was actually under house arrest on his own estate. However, this did not mean that the commander was not aware of the events. He attentively followed the actions that the young French generals conducted in Europe, analyzed the new things that they brought to the practice of warfare. So, barely having received the Supreme Rescript on the appointment from the Emperor, Suvorov began to act. It must be said that, being a convinced monarchist, he attached special importance to the war with France, although for the whole of his many years of practice he had to command the combined forces for the first time.

The Russian army was formed from three corps: the corps of Lieutenant General A.M. Rimsky-Korsakov, a corps of French émigrés serving in the Russian army, under the command of Prince L.-J. De Conde, and the corps, headed by Suvorov himself.

The Russian army was formed from three corps: the corps of Lieutenant General A.M. Rimsky-Korsakov, a corps of French émigrés serving in the Russian army, under the command of Prince L.-J. De Conde, and the corps, headed by Suvorov himself.During the journey, the commanders took a number of measures aimed at preserving the troops, which were to go thousands of kilometers, from providing them with the necessary amount of materiel and food to rest on the march. But the main task of the commander was to train the troops, and first of all the Austrian ones, who were inclined to under-act.

15 April in Vallejo Suvorov began to lead the coalition forces. His decisive actions quickly ensured a number of Allied victories. In close cooperation with the squadron of Ushakov, Suvorov cleared almost the whole of Italy from the French for several months. Despite repeated attempts by Vienna to intervene in the actions of the commander, he, given the current situation, continued to adhere to his plan. However, the three major victories of the Allied armies that soon followed caused an even more ambiguous reaction. Now the commander was obliged to report to Vienna on each of his decisions, and only after approval by the Austrian Military Council, he was given the opportunity to act. Such a situation fettered the actions of the commander. In one of the letters to Count Razumovsky, Suvorov wrote: “Fortune has a bare back of the head and long, hanging hair on her forehead, her lightning flying without grabbing her eyes — she already does not return.”

The victory over enemy troops on the Adda River (26 — 28 on April 1799) gave the Allies the opportunity to capture Milan and Turin. The next battle, on the river Trebbia, took place on June 6, when Suvorov, at the head of the 30-thousandth army, was forced to rush to help the Austrians, attacked by the French army of General J. MacDonald. Under the conditions of the summer heat, the Russian army, when striding, and when running, overcoming 38 km in Trebbia for 60 hours, arrived at the place just in time and without any respite entered the battle, hitting the enemy with swiftness and surprise of the onslaught. After the 2 day of fierce fighting, MacDonald ordered a retreat. Suvorov was determined to finish off an exhausted enemy, who lost half of his army, and to launch an invasion into the borders of France. But the leadership of Austria had its own opinion on this matter, and the Russian commander, indignant to the depths of his soul by the “ineradicable habit of being beaten,” was forced to retreat. The French, who had the opportunity to regroup and gather new forces, moved their troops, led by a young talented General Joubert, to Alessandria - to the location of the allied forces. The last battle of the Italian campaign took place near the town of Nevi. Started in the early morning of August 4, it ended with the complete rout of the French. But again, according to the position of the Vienna Court, the decisive blow to the enemy was never dealt. As a result, Russian troops were sent to Switzerland to join the corps of General Rimsky-Korsakov for a subsequent joint attack from there on France.

According to the plan developed by the Austrians, the Russian troops were to replace allies there, who, in turn, moved to the areas of the Middle and Lower Rhine — Austria intended to regain them first. The organizers of this move, however, did not consider it necessary to involve direct implementers in the development. In addition, the Austrians did not want the Russians to stay in Italy for a long time. The reason was simple: Suvorov in the liberated territories actually restored the local municipal government, but this did not suit the Austrians, who already considered Italy their own.

According to the originally developed plan, the army of Suvorov was to leave the city of Asti on September 8 and move in two columns: the corps of General V.Kh. von Derfelden and the corps of General AG Rosenberg, who was ordered to join 11 September in Novara, then go along towards the city of Airolo. Artillery and wagon train were supposed to be moved separately, through Italy and the province of Tirol to Switzerland.

Meanwhile, having received an order for the complete withdrawal of troops from Switzerland, the commander-in-chief of the Austrian troops, Archduke Charles, began to implement it immediately. Suvorov, who learned about this on September 3, was forced to immediately, without waiting for the surrender of the garrison of the fortress of Tartons, to speak in Switzerland. But at that very moment the French made a desperate attempt to unblock the besieged citadel, while Suvorov had to return and force the garrison to capitulate. The loss of two days in this situation could lead to the most serious consequences.

The army, numbering about 20 thousand people, having overcome more than 150 km of the way, arrived in the Tavern place not through 8 days, as planned, but through 6. Suvorov needed to reach the Gotthard pass as quickly as possible. While still in Asti, he ordered the Austrian field marshal M. Melas to prepare and concentrate before the army in the Tavern the baggage bag necessary for further advancement (the allies were supposed to provide mules with fodder and provisions to 15 September). But having arrived at the Tavern, Suvorov did not find either one or the other, and only 1 of September around 500 animals with part of the forage stock arrived on the spot. Partially using the Cossack horses to fill in the missing ones and completing the preparations for the march, 18 of September Suvorov begins his nomination to Saint Gothard. Time is inexorably compressed. The “overall attack plan” developed by Suvorov’s headquarters in the Tavern under the conditions of a changed situation and recommended for implementation by Austrian commanders F. Hotz and G. Strauch suggested that all Allied forces would attack the 650 km front along the right bank of the River Rois Aare, to Lucerne.

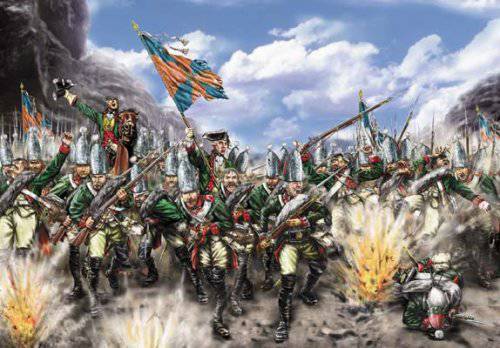

Suvorov attached particular importance to the capture of Saint-Gothard. In this regard, he made sure that a rumor was spread that the offensive should begin no earlier than October 1 (in terms of September 19 originally appeared, but because of the delay in the Tavern, it took place September September). The French in Switzerland had several advantages over the upcoming allies: a more advantageous strategic position, considerable experience in waging war in mountainous conditions and good knowledge of it. Suvorov, in cooperation with the Strauch detachment, was to knock out the French, led by the most experienced General K.Zh. Lekurbom. For the French, the Russian offensive, which began on the early morning of September 24, was precisely this pass that was completely unexpected.

The numerical superiority of the allied forces at the time of the attack, according to some researchers, was 5: 1, but despite this, the first attacks of the French skillfully repulsed. However, the attackers, applying the tactics of a bypass maneuver, constantly forced them to retreat. By noon after heavy fighting, Suvorov climbed to St. Gothard. Then the slightly rested troops began to descend, and by midnight the pass was taken - the French retreated to Urzern. The next day at 6 in the morning, the Allied columns moved to Geshenen through the so-called “Urian Hole” - a tunnel about 65 meters long in the mountains, about 3 meters in diameter, which was kilometers in 7 from Urzern. Immediately after the exit from it, the road, which hung in a huge cornice over the precipice, abruptly descended to the Devil's Bridge. This bridge, thrown over the deep gorge of Shellenen, in fact, connected with a thin thread the north of Italy and the southern borders of the German lands.

A devil's stone hung from the opposite side of the gorge, from which both the exit from the tunnel and the bridge itself were visible. Therefore, the advance guard of the attackers who emerged from the “Hole” immediately came under heavy fire from the enemy.

By the beginning of the battle, the French sappers could not completely destroy such an important crossing, and during the battle the bridge consisted of two halves - the left-bank arcade was partially undermined, while the right remained intact. The Russians, having dismantled the wooden structure that was standing nearby, connected the logs and quickly restored the bridge, rushed along it to the opposite shore. The French, feeling that they were beginning to bypass from the flanks, retreated, but their pursuit was postponed until the full restoration of the bridge.

After 4 hours of operation, the movement of troops was resumed.

In the meantime, in the area of Zurich, where the Allied army was to emerge, the following happened. After the withdrawal of the Austrian units to Germany, the army of Rimsky-Korsakov and the corps of Hotz became a tasty morsel for the commander-in-chief of the French troops in Switzerland, Massena. Only a water barrier did not allow him to attack immediately. Hearing from his spy at the headquarters of the Russian army, Giacomo Casanova, that the Russians were planning to launch an offensive on September 26, Massena delivered a decisive blow with lightning speed. On the night of September 25 in 15 km from Zurich, at Dietikon, a group of brave souls, having crossed by swimming only with cold weapons and removing the Russian patrols, provided the crossing of the main body of Massena's troops. In a two-day battle, the armies of Rimsky-Korsakov and Hotz were defeated. Hotze himself in the first minutes of the battle was ambushed and killed. This news was so strongly reflected in the fighting spirit of the Allies, that almost all of them surrendered. As a result, the total losses of the Allies amounted to about nine thousand people, and the remnants of the Russian troops went to the Rhine. Such a catastrophic defeat could not but affect the further course of the entire campaign.

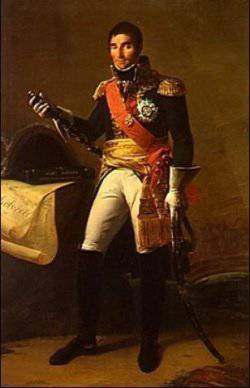

He was born 6 in May 1758, in Nice, in the family of an Italian wine-maker and was the third of five children. When Andre turned 6, his father died, and his mother soon remarried. In 13 for years, he ran away from home and was hired as a cabin boy on one of the merchant ships. After 5 years of marine life, Massena joined the army. Having served in 1789 year before the rank of non-commissioned officer, he realized that for a man of his origin, further promotion is unlikely to be foreseen, and he retired. Soon, Massena got married and started a grocery business. Judging by how quickly he got richer, he was obviously smuggling. One way or another, but knowledge of each trail in the Maritime Alps served him well in the future. When the French Revolution reached the backwater where Massena lived with his family, he, realizing all the advantages of serving in the republican army, joined the national guard detachment and began to move quickly through the ranks. In 1792, he was already in the rank of brigadier general, and a year later Massena became a member of the famous battle of Toulon. In his submission at that time he served as an unknown captain Bonaparte, who commanded artillery in this battle. After the capture of Toulon, each of them received a new rank: Massena became a divisional, and Bonaparte became a brigadier general.

He was born 6 in May 1758, in Nice, in the family of an Italian wine-maker and was the third of five children. When Andre turned 6, his father died, and his mother soon remarried. In 13 for years, he ran away from home and was hired as a cabin boy on one of the merchant ships. After 5 years of marine life, Massena joined the army. Having served in 1789 year before the rank of non-commissioned officer, he realized that for a man of his origin, further promotion is unlikely to be foreseen, and he retired. Soon, Massena got married and started a grocery business. Judging by how quickly he got richer, he was obviously smuggling. One way or another, but knowledge of each trail in the Maritime Alps served him well in the future. When the French Revolution reached the backwater where Massena lived with his family, he, realizing all the advantages of serving in the republican army, joined the national guard detachment and began to move quickly through the ranks. In 1792, he was already in the rank of brigadier general, and a year later Massena became a member of the famous battle of Toulon. In his submission at that time he served as an unknown captain Bonaparte, who commanded artillery in this battle. After the capture of Toulon, each of them received a new rank: Massena became a divisional, and Bonaparte became a brigadier general.Being a resolute man, Massena was distinguished by courage more than once in battles. Thus, in one of them, he, on horseback, made his way through the pickets of the enemy to his surrounded detachment, and in front of the astonished Austrians with such arrogance, led him out of the encirclement without losing a single person. Nevertheless, he had two great weaknesses - fame and money. Thirst for acquisitions nearly served as the cause of the revolt of the hungry and ragged Roman garrison, of which he became head in 1798 year.

In 1799, Massena was appointed head of the Helvetic Army in Switzerland. In 1804, he received a marshal's baton from Bonaparte, in 1808, he was given the title of Duke of Rivoli, two years later - Prince of Eslinga, and in 1814, he betrayed his emperor, going over to the Bourbons. This act would be appreciated “in dignity” - in 1815, Massena became a peer of France and died two years later.

September 26, having restored all the crossings on Reuce, Suvorov's troops continued to move. Approaching the city of Altdorf, Suvorov unexpectedly learned that the road to Schwyz, before which there was 15 km, does not exist. Instead, there is a narrow path along which either a single person or a wild beast can walk. Undoubtedly, it was necessary to turn back and go the other way, but Suvorov, for whom there was no concept of "retreat", decided to move along the "hunting trail." At this time, Massena, who had learned about the advancement of Suvorov to Schwyz, immediately strengthened all the local garrisons, and Suvorov, who still did not know anything about the defeat near Zurich, went into the trap set for him. September 27 in the morning 5 movement started the vanguard of Bagration. This 18-kilometer transition was incredibly difficult.

More than half of the pack animals were lost, the army still lacked food.

Having entered 28 September in Muotatal, Suvorov finally learns from the local population about the defeat of Rimsky-Korsakov and Hotz. Almost instantly, the balance of forces changed in favor of the enemy almost 4 times. In addition, now Massena, who was eager to capture the Russian commander, spoke directly against Suvorov. Arriving in Lucerne, Massena studied in detail the relief plan of Switzerland, and then on the ship reached Lake Sezerorf on Lake Lucerne, where General Lecourbe was waiting for him. Having studied the situation in detail, Massena decided to conduct a reconnaissance in the Shekhenskaya Valley. And making sure that the enemy really went to the Muoten Valley, he gave the order to block the waste to Altdorf.

Suvorov, 29 of September, having ascertained the defeat at Zurich, decided to make a connection with the remaining parts of the allies. As a result, the Russian army began to withdraw from the valley, and the French began to pursue it. September 30 was the first battle in Muoten Valley, unfortunate for the last. Frustrated by this outcome, Massena decides to lead the next attack in person. On the morning of October 1, advancing to the bridge and quickly restoring it, the Republicans attacked Russian pickets. Those with the order not to fight, began to retreat. Meanwhile, General A.G. Rosenberg, who was expecting such a turn of events, built his battle formation in three lines. Seeing that the Russians were retreating, the French rushed into pursuit. At this point, the retreating party dispersed on the flanks. And then the French gaze was an unexpected picture. Right in front of them, the whole battle formation of Rosenberg was revealed. The French, inspired by the presence of the commander, confidently rushed to the position of Russian. The Russians, closing bayonets, went on the attack. With lightning bypass maneuvers they captured three guns and a large number of prisoners. Surrounded by the French rearguard was finally overturned and in complete disarray rushed to the Schengengen bridge. Massena was forced to withdraw the remnants of his troops to Schwyz, which the French managed to hold, although the Second Muoten battle turned out to be a very difficult defeat for them. Massena himself was nearly captured. In the confusion of battle, non-commissioned officer Makhotin began to make his way to the enemy general. Having approached closely, he, having grasped his epaulet, tried to pull Massena off his horse. The French officer, who came to the rescue, managed to knock over Makhotin, but the golden general's epaulette remained in his hand. This fact was later confirmed by the captive adjutant Guyot de Lacour.

Now, in order to break out of the encirclement, Suvorov needed to break through to Glarus and then go on to join up with the remnants of the Rimsky-Korsakov army. The Russians took Glarus, but the French managed to close the shortest way to connect Suvorov and Rimsky-Korsakov. To get out of the encirclement, the Russian troops needed to overcome another pass - through the Panix mountain with the height of 2 407 meters. This transition was perhaps the most difficult for the army of Suvorov. For those soldiers and officers who survived all his troubles, he remained in memory as the most terrible test of will and physical strength. Nevertheless, the hungry and immensely weary army overcame it. The first, 6 of October, was the vanguard of General MA Miloradovich. The appearance of the Russian army was deplorable - most of the officers had no soles on their boots, the uniforms of the soldiers were torn almost to shreds. On October 8, the entire army of Suvorov reached the city of Chur, where the Austrian brigade of Aufenberg was already stationed. Here, all prisoners in the number of 1 418 people were transferred to the Austrians.

After a two-day rest, Russian troops moved along the Rhine and October 12 camped at the village of Altenstadt. For two days the soldiers rested, washed and eaten off, and by the end of the second they were ready for the march again. However, this did not take place. In his “Note with general remarks on the 1799 campaign of the year”, dated 7 in March 1800, Suvorov seemed to draw a line under all that happened: “So, the mountain gave birth to a mouse ... Without owning any art of warfare or peace, the cabinet (Austrian. - Note auth.), steeped in guile and deceit, instead of France, forced us to drop everything and go home. ”

The campaign was lost, and meanwhile Suvorov, granted to her by Emperor Paul I in 1799, with the title of Prince of Italy and the title of Generalissimo, did not suffer a single defeat. Despite all these circumstances, the glory of the Russian weapons in this campaign was not defiled. No wonder that the same André Massena, who managed to defend France, later said that he would give all his 48 campaigns during the 17 days of Suvorov’s Swiss campaign.

After a short time, Suvorov drew up a new campaign plan against the French, where it was planned to use only Russian troops now, but he was not destined to be realized - on May 6 on May 1800, the old commander died.

Information