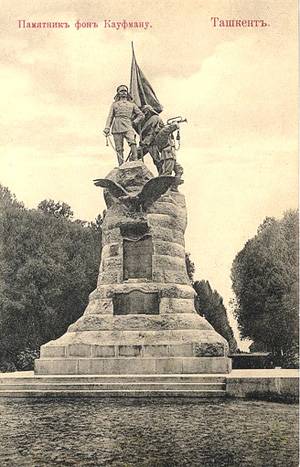

Organizer of the Turkestan Territory K.P. Kaufman

The process of developing new and, besides, vast territories has never been either quick or easy. Much, of course, depends on the methods and methods that ultimately in one way or another affect the result. It is possible, arranging a mass extermination and robbery of the local population under the pretext of forced its initiation to the true faith, on carts with gold, in the end, to slide into degradation and poverty. Driving the freedom-loving tribes on the reservation, the seas with their hunger and cold, later declare the country - a political rival a "prison of nations". And how easy it is not to bother thinking about millions of natives who do not unbend on the plantations, arguing in the salons about the burden of the white man.

Behind the development of territories are people - their will, charisma and perseverance. Behind the first research and military expeditions and detachments came the turn of a long-term development, not always proceeding in calm conditions, a time of bold, courageous and at the same time wise and fair. Many were engaged in the development, or rather, the assignment of resources and funds sent from the center. But there were others who left their deep mark on the distant frontiers. They were not Kipling's heroes with his “burden”, although their burden was heavy and sometimes threatened to fall out of hand. One of these was Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman.

Descendant of an ancient race

Russia has traditionally favored foreigners and willingly accepted them into the service. Was no exception and the genus von Kaufmanov. Its origins go to medieval Swabia, from where the surname Kaufman moved in XVII to Austria. The first mention of it dates back to the middle of the XV century. In 1469, Ebergard Kaufman received a noble title from the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. His son John for merits during the siege of Vienna by the Turks was elevated by Charles V to imperial knighthood. The first representatives of the von Kaufman family entered the Russian service in the second half of the 18th century. The grandfather of the future governor of Turkestan, called in the Russian manner by Fyodor von Kaufman, served in the army of the Russian Empire as a lieutenant colonel, and died from a wound in battle against the Turks. His ten-year-old son Peter was left an orphan. Empress Catherine II ordered to identify the boy in the gentry corps, appointing him guardians.

Peter F. von Kaufman participated in the Patriotic War of 1812 and the foreign campaign of the Russian army in the Russian-Turkish war of 1828 – 1829. and the Hungarian campaign 1848. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, was awarded the Order of St. George 4 degree and large estates in the Kingdom of Poland. After returning from France, where Peter F. von Kaufman served as part of the Russian occupation squad, March 3 1818 in the town of Deblin, which, along with other former Polish lands, was transferred to Russia by the decision of the Vienna Congress, he had a son named Konstantin . The future governor of Turkestan had a far from sentimental childhood of a noble offspring guarded by hordes of mothers and nannies. From an early age, young Kaufman had a chance to get acquainted with the intricacies of bivouac and hiking life, because his father constantly took him with him.

Upon reaching 14 years, Konstantin was determined to study at the Main Engineering School. The son of the general showed himself well in the sciences, was executive and disciplined. In 18 years Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman received his first officer rank - field engineer-ensign. A year later, after graduating from honors officer classes and receiving the rank of engineer-lieutenant, he was sent to the army. One of the fellow practitioners of the young Kaufman was Edward Totleben, a brilliant future engineer, hero of the defense of Sevastopol.

In subsequent years after graduation, Kaufman served consistently in Novo-Georgievsk and Brest-Litovsk. In 1843, he was assigned to the Caucasus, to the Tiflis engineering team. This territory at that time was a theater of military operations between the Russian troops and the mountain tribes operating against them. Soon Konstantin Petrovich was promoted to captain with the appointment of a senior adjutant at the headquarters of a separate Caucasian corps. Kaufman spent almost 13 years in the Caucasus, and these years did not seem like a quiet garrison service somewhere in the central provinces. He regularly participated in various combat operations, campaigns and captures of villages. During the Crimean War, commanding the Caucasian Sapper Battalion, he became a direct participant in the siege of the fortress of Kars, well-fortified with the participation of the British, in 1855.

During the years of service in the Caucasus, Kaufman was awarded several orders, among which stood the Order of St. George 4 degree for taking the aul Gergebil and the golden award sword with the inscription “For Bravery”. Kaufman’s two other less pleasant reminders of the Caucasian Campaign were two injuries. His achievements were noted at the very top - in 1856, General Kaufman was appointed a member of the board of the Nikolaev Academy of Engineering. Two years later he was honored to remain in the retinue of Emperor Alexander II. The era of universal reform, which began in 1861, found Major General Kaufman as Director of the Office of the War Ministry. The Russian army was in the process of transformation, a military district system was created from scratch. Konstantin Petrovich took part in this process in the most direct way: he was a member of various committees and commissions to discuss and introduce new elements of the military organization. By the highest order, he was given the right to vote at the Military Council. Four years of activity as director of the Office were marked with the rank of lieutenant general and the honorary title of adjutant general.

In 1865, Mr. Kaufman was appointed Governor-General of Vilna instead of the retired M. N. Muravyev. However, he held this post for a relatively short time - in the fall of 1866, the lieutenant general was summoned to Petersburg. In October, 1866, by the highest decree, Kaufman was sent on 11-month leave with the rank of adjutant general. Emperor Alexander II had far-reaching plans for this talented man. Russia increasingly penetrated the intricate and not very simple Central Asian affairs, where often fashionably trimmed English sideburns could be seen in the midst of saxaul thickets. The situation was difficult and on the eve of the penetration of Russia into the depths of Central Asia, the construction of iron roads, the struggle against local khanates in Turkestan who did not disregard the slave trade, a talented governor was needed. He had to combine strong-willed and diplomatic qualities at the same time, to be an excellent organizer and, most importantly, a good military man.

In St. Petersburg, they decided that Konstantin Petrovich could not be more suitable for these broad demands. Therefore, even before the end of the extended 14 leave in July 1867, Lieutenant-General von Kaufmann was appointed Governor-General of Turkestan and commander of the Turkestan Military District. He received broad powers with the right to begin hostilities and make peace based on the situation. In October 1867, after solving organizational issues, Lieutenant General Kaufman left St. Petersburg for a new duty station. At first glance, the route they chose was not the fastest and most optimal, which was the route to Tashkent via Orenburg. Kaufman set off in a roundabout way: through Semipalatinsk, Sergiopol and the center of the Semirechensk region - the fortress of Faithful. This was done intentionally, in order to follow the local affairs and get acquainted with the vast region and its customs. Special attention was paid to the local administration. November 7 Kaufman arrived in Tashkent. So began his governorship.

Turkestan governor

Konstantin Petrovich accepted the territory entrusted to him in a form that was far from brilliant. The administration, repulsed by the hands and supervision, felt itself supreme and therefore uncontrollable. It was not the region that flourished, but bribery, embezzlement and various embezzlements. All of the above could not but affect the attitude of the local population to the Russians. The foreign policy situation also did not favor calmness - Turkestan was surrounded by feudal khanates, the best way to dialogue with which was the use of force.

The once rich and powerful Kokand Khanate was now weakened by the unsuccessful attempt to clarify relations with the Russians, undertaken in 1860. The result was several sensitive defeats for Kokands and the fall of 15 in June 1865 in Tashkent. They painfully perceived the institution of the Russian general-governorship, believing that they would now be oppressed and destroyed. The mass exodus of the population to the territory of the neighboring khanates and China began. Faced with such incessant commotion, Kaufman found it necessary to send a letter to the Kokand Khan, where in accessible terms he explained to him the full benefits of friendship with the Russians, and that in the event of hostile actions by the Khan, no fortifications and armies would save him. It was especially emphasized that Russia is not going to conquer his country and destroy its population.

Somewhat more difficult relationships developed with the belligerent and still inaccessible Khiva khanate. Located in remote, desert areas, it continued to pester its neighbors — primarily Russia and, to some extent, Persia — by systematically plundering trade caravans and the slave trade. It was necessary to solve this problem in the near future, because they planned to pull the railway through the territory of the Khanate. Starting off the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea, the road was supposed to connect Russia and Turkestan.

Of the large formations, there was also a rather problematic Bukhara. Local authorities were very frightened by the capture of Tashkent and began to threaten the Russian representatives with holy war. Difficult diplomatic upheavals led to the detention of the Russian embassy headed by the official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Struve as hostages. The immediate response to such an event was naturally a military expedition, the capture of the Hagenta fortress in 1866, the release of the embassy and the prayer of the Emir Muzaffar for peace. Negotiations in Orenburg did not lead to any intelligible results, gangs of Bukharians continued to rage, attacking caravans and fortified points, and Orenburg Governor-General N. A. Kryzhanovsky resumed hostilities. In Petersburg, these actions were perceived with disapproval and grumbling about abuse of authority. Turkestan was removed from its jurisdiction, and a governor-general was formed on its territory, at the head of which they placed Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman. Thus, together with the new appointment, the governor inherited a war that had not yet ended with Bukhara.

Arriving in Tashkent and calming down the Kokand Khan, Kaufman presented the terms of a peace conclusion to the Bukhara emir, which were predictably rejected. The fighting resumed. At the end of April, 1868, together with the 8-thousandth detachment, which had 16 tools, advanced from Tashkent towards Samarkand, where, according to intelligence data, the Bukhara emir gathered a large army. By the beginning of May, Russian troops approached the capital of the Bukhara Emirate. 1 May 1868, the infantry of General Golovachev, right in front of the enemy, forced the river Zeravshan and hit with bayonets. The Bukhara army, outnumbered by its enemy, but absolutely inferior in terms of discipline and organization, quickly fled.

Samarkand opened the gates, and on May 2, Kaufman’s troops stepped into one of the most ancient cities in Central Asia. The local leadership, feeling the power of the newcomers and therefore quickly and correctly orienting themselves in the situation, presented the Russian commander with bread and salt and his most sincerely sincere wishes to pass into citizenship to Emperor Alexander II. For the capture of Samarkand Kaufman, in addition to the royal favor, was granted the Order of St. George 3 degree. Konstantin Petrovich knew well the price of sincerity of the most ardent and heartfelt statements of loyalty and loyalty. Therefore, his detachment remained in Samarkand, awaiting the arrival of reinforcements from Tashkent.

Parliamentarians were sent to the Emir of Bukhara with the proposal to begin peace negotiations. However, the letter remained unanswered, and cruel reprisals were committed against the envoys. Once again, making sure that no dialogue with the Emir could be established, the military operation was continued. Leaving a garrison in Samarkand, Kaufman moved south, where on May 18 defeated the Bukharians at Katta-Kurgan. As usual, the enemy repeatedly surpassed the Russian expeditionary forces, yielding in quantity and quality of firearms weapons. Having suffered huge losses in the last battles, the emir was forced to change his tone and send his ambassadors to the negotiations, obviously knowing for sure that their bloodthirsty Russian heads would not be cut off.

The delegation of the Bukharians at the beginning shook their rights, as if there were no Samarkand’s downfalls and numerous defeats of the troops of the Emir Muzaffar. I had to explain to them that the emirate was far from being in a bright position, and therefore he was offered two options to choose from. According to the first, the emir paid Russia for 8 years more than 4 million rubles of indemnity, after which all the lands conquered by the Russians would be returned to him. According to the second, Muzaffar reimbursed only military expenses in the amount of 120 thousand rubles, but recognized all the military conquests of Russia. There was no money in the Emir’s treasury, and the Bukhara side agreed to the second option.

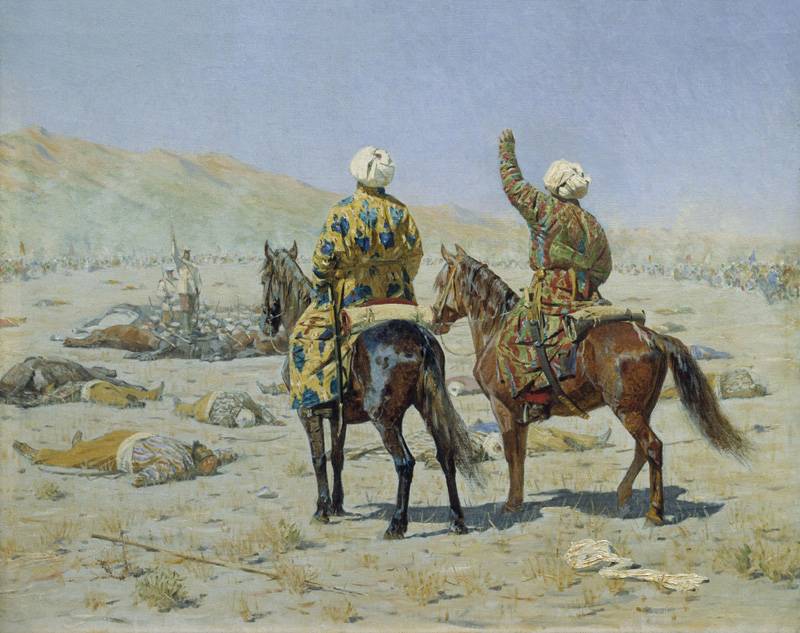

Ambassadors asked for ten days to collect the necessary funds, but very soon the Bukhara side broke the truce, suddenly attacking the Russian troops. It became clear that new efforts would be needed to bring Muzaffar to a state of agreement. 2 June 1868, in a fierce battle on the Zarabulak heights, the Emir's army suffered a cruel defeat. Russian troops were no more than 2 thousand. People, they were opposed by many times superior forces, which were defeated and fled.

The officers advised Kaufman to go deep into the territory of the enemy and strike directly at Bukhara. However, Konstantin Petrovich did not consider his own already exhausted forces sufficient to make a trip to a major city. In addition, he was increasingly worried about the situation left behind in the rear of Samarkand. Since the main forces of the Russian troops left the city, the situation there has gradually begun to heat up. The mullahs were making more and more obvious agitation aimed at the uprising. Numerous signals from representatives of the Persian and Jewish communities about the impending danger were simply ignored.

2 June, the day of the battle at Zarabulak heights, Samarkand rebelled, and a small garrison left by Kaufman under the command of Major Shtempel (no more than 600 people) was besieged in the city citadel. The position of the defenders turned out to be very difficult - they had limited ammunition, the number of attackers exceeded them by an order of magnitude - nomadic tribes loyal to the emir joined the inhabitants of Samarkand. All attempts to inform Kaufman about the incident were unsuccessful - messengers, mostly from local ones, were successfully intercepted. Kaufman's detachment moved to Samarkand, but its speed would be higher, have the commander any information about the events in the city. Only 7 of June, being approximately 20 km from Samarkand, was the next brave man finally able to reach the Russian camp and report that the citadel’s garrison was besieged and in urgent need of help. The next day, Kaufman's detachment entered the city, scattering crowds of rebels. Exhausted garrison of the citadel enthusiastically met their liberators. By the way, among the besieged was Ensign Vereshchagin, who was an artist under Kaufman.

Systematic military failures, unrest among the population and, moreover, the lack of funds to continue hostile actions against Russia made Amir Muzaffar extremely accommodating. On June 12, he sent Kaufman a letter of utter despair asking the commander to accept his capitulation and allow him to make a pilgrimage to Mecca. Peace with the ruler of Bukhara was concluded on benign conditions, despite his repeated treachery. Samarkand and Katta-Kurgan districts departed to Russia, during the year the emir pledged to pay a contribution to 500 thousand rubles. In addition, he had to take care that no robber raids were carried out on Russian territory. Of the territories conquered from the Bukhara emirate, the Zarafshan district was formed, headed by Major General Abramov.

In early July, Kaufman made a speech in Tashkent, where at that time persistent rumors were spreading about the defeat of the Russian troops and the capture of Samarkand by the troops of the Emir. The appearance of the governor-general dispelled these doubts and stopped the attempts of the local population to make a riot. In the emirate, internecine feud soon began. Part of the nobility, dissatisfied with the signing of the treaty with the hated Russians, raised a revolt against Muzaffar, headed by his eldest son, Abdul-Malik. In such a difficult situation, the emir was forced to turn to no one else, but to the same “hated Russians” who, in the person of General Abramov, helped to cope with the insurgency.

Kaufman, meanwhile, was summoned for service to St. Petersburg, where 1868 arrived in August. The fact is that the active policy of Russia in Central Asia caused an acute nervous breakdown in the “respected Western partner” - England. Therefore, the governor was torn away from directly fulfilling his duties for an urgent report to the emperor. Chancellor Gorchakov, fearing the reaction of Foggy Albion, pestered Alexander Nikolayevich. At the king’s audience in response to the demand to return Samarkand and Katta-Kurgan to the Bukharians, Kaufman firmly objected, arguing that such steps would sharply undermine Russia's prestige and position in Central Asia. The empire will then be constantly compared with England, and this comparison in ways of behavior was always not in our favor. The king relented and offered Kaufman to state his point of view to Gorchakov in the same convincing manner. The Chancellor had to take into account the opinion of the emperor and reassure the "partners" who had already uttered in the press. In July, 1869, Mr. Kaufman returned to Turkestan and began to fulfill the difficult duties of the Governor-General.

Khiva problems

Russia was seriously thinking about the development of its communications in Central Asia, for which it was planned to extend its railway to the depths. The initial plan of the Samara-Orenburg-Tashkent line was considered too long and costly and was revised in favor of the shorter one - from the east coast of the Caspian Sea through the desert lands to Tashkent. The problem was that the branch was supposed to pass through the territory of the belligerent and completely incompetent Khiva khanate. The main occupation of the inhabitants was robbery, the theft of livestock and prisoners. The local khan refused to enter any diplomatic relations. Upon arrival in 1867 in Turkestan, Kaufman sent a very polite letter to Khiva's governor Muhammad Rahim-Khan, in which he informed the Khan about his appointment and about Russia's desire to maintain good-neighborly relations. The answer was received only in the next year, 1868, and he was deprived of any hints, even of elementary diplomatic politeness.

Clearly understanding that it would be impossible to come to an agreement with Muhammad Rahim Khan in an amicable way, Kaufman began to personally develop a plan for the upcoming campaign to pacify Khiva. The central place in his plan was the creation of a fortified fort in the Krasnovodsk Bay, which was reported in a special note to the Minister of War, Count Milyutin. The decision at the top was not easy - Britain was painfully concerned with almost any Russian activity in Asia, seeing in this a stumbling block to the preservation of the “pearl” of her colonial empire, India. Finally, the authorities gave the go-ahead, and in 1869, Lieutenant Colonel Stoletov, together with a group of engineers and a small detachment, landed in Krasnovodsk Bay, where the fort Krasnovodsk was founded. The Khiva ruler, sensing a threat to his security, responded with an angry letter full of reproaches and threats. Such a reaction of the khanate even more convinced Kaufman of the need to organize an armed expedition.

Initially, the operation was planned to be held already in 1870, however, due to unrest among the local population, unrest in Samarkand and Tashkent, the dates were postponed. At the beginning of 1873, an agreement was reached on the delimitation of spheres of influence between Russia and England in Central Asia, and there were no longer any obstacles to the implementation of Kaufman’s plans. The expedition against Khiva began in late February - early March 1873 of the year. Russian troops advanced deep into the Khanate from several sides: from the coast of the Caspian Sea, from Orenburg and Tashkent. Kaufman himself led the largest convoy, speaking from Tashkent. The hike was carried out in extremely difficult conditions: a constant lack of water, the death of pack animals, sand storms and, of course, exhausting heat. Along the way, the troops were constantly attacked by the Khivans.

Nevertheless, by the end of May, Russian forces began to concentrate at Khiva, and after the bombardment and decisive assault under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Skobelev, the demoralized city was taken. Khiva Khan himself hastened to flee to the Turkmen tribes that remained loyal to him. A rich library was discovered in his palace and subsequently sent to Petersburg. Also, the throne of the Khiva Khans was brought to the capital as a trophy. However, the Russian commander invited the fugitive Muhammad Rahim Khan to return. He was treated with respect, and soon a peace treaty was signed between the Russian Empire and Khiva, according to which Khan recognized himself as the humble servant of the emperor, ceded part of the land, paid a contribution of 2 million rubles during 20 years. A separate item was the release of slaves in the territory controlled by Khiva - about 40 thousand people, mostly Persians, received freedom. For bringing the Khiva khanate to order, Konstantin Petrovich Kaufman was awarded the Order of St. George 2 degree, and the next year, 1874 was promoted to engineer-general.

Kokand

The pacification of Khiva made an impression on the Central Asian khans, but the calmness in it turned out to be a temporary phenomenon. Kokand Khan Khudoyar was vitally interested in maintaining good neighborly relations with Russia, because he had a good income from trade with the empire. However, not everyone in his circle liked this situation. In July, 1875, in Kokand, unrest began, soon turning into an ordinary civil war. The notable Kipchak Abdurakhman-Avtobachi, known for his Russophobian sentiments, stood at the head of the rebels. All those who were dissatisfied with the presence of Russians in the country, nobles, counting on personnel changes, and almost all clergymen took his side. Khudoyar, left without support, fled to Russian territory, and his eldest son, Nasr-Eddin, was proclaimed the “ideologically correct” ruler of Kokand.

Already in August, 1875, the 15-thousandth Kokand army invaded Russian territory and laid siege to the city of Khojent. Kaufman’s reaction was operational — an expeditionary detachment was made up of 16 infantry companies, 8 Cossack hundreds, 20 guns and 6 rocket launchers. In the second half of August, these forces were already concentrated by Khojent. Having released the city, Kaufman moved to the Mahram fortress, where, according to intelligence data, the main forces of Abdurahman-Avtobachi were located. On the morning of August 22, Mahram held a battle with the Kokand army, which was defeated and put to flight. During the retreat, she suffered huge losses from concentrated rifle fire. The losses of the Russian side were limited to five killed and eight wounded.

Leaving the garrison in Makhram, Kaufman 26 August 1875 spoke to the capital of the Khanate of Kokand. 29 August the city was taken, and, not stopping there, Kaufman continued the expedition. 9 September his squad reached Margilan. Here, for the further prosecution of the Avtobachi troops, which had lost any semblance of organization, a mobile, or, as it was said, flying unit under the command of Major General Skobelev responsible for this task was formed. There were six Cossack hundreds, two infantry companies, planted on arbs and a battery of horse artillery. Skobelev began the persecution and occupied Osh, the easternmost city of the Kokand Khanate, without a fight. The troops of Abdurakhman-Avtobachi were finally scattered, and he fled abroad.

Having completed the task, Skobelev's squad returned to Margilan. So in a short time, Kaufman managed to take control of the territory of the entire Kokand Khanate. 22 September 1875 was signed a peace treaty with Khan Nasr-Eddin on the type of those that were concluded with Bukhara and Khiva. The ruler of Kokand recognized the supreme power of the Russian emperor, transferred part of his lands to Russia and paid indemnities. From the former Kokand territories, the Namangan district was formed, at the head of which was Major General Skobelev. However, this was not the end of the Kokand epic. Khan, who signed a peace treaty with Russia, did not control the whole situation in the country and soon Abdurahman-Avtobachi, who remained at large, again raised an uprising, the center of which was the city of Andijan. Nasr-Eddin was overthrown, and a relative of Khudoyar Foulash-bek was proclaimed khan.

Only after a series of successful operations undertaken by General Skobelev's troops, this uprising was put down, and 24 in January 1876, having lost the ability to resist, Avtobachi surrendered to the Russian troops, after which he was exiled to Ekaterinoslav. Foulash-bek taken prisoner, distinguished by cruelties and crimes, was convicted and hanged in Margilan. Khan Nasr-Eddin returned from emigration to Kokand, but then Kaufman, who had the appropriate authority from the emperor, decided that it was impossible to leave the Khanate, systematically showing concern, without supervision, and ordered Skobelev to arrest the Khan. 7 February Nasr-Eddin was taken into custody and sent to Orenburg. 7 February, Alexander II issued a decree according to which the Kokand Khanate was part of the Russian Empire, and the Fergana region was formed from its territory.

Last years

Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman did a lot to expand and strengthen the borders of the Russian Empire. He is famous not only for his military campaigns and diplomatic efforts, but also for his scientific and administrative activities. Local customs were not destroyed or altered by the Russian authorities — local self-government and leaders from among those whom they themselves would choose from among their own were given to local ones. Much has been done to explore the region and study its geology. The resettlement of the Russian population to Turkestan was encouraged in every way.

Kaufman was an honorary member of Moscow University and the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Surviving the attempt and death of Emperor Alexander II, in March 1881, Mr. Kaufman fell ill, and did not recover, and died on May 4, May 1882, in Tashkent, where he was buried. Five years later, his ashes were transferred to the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior. After the transfer of titles and awards, the “Organizer of the Turkestan Territory” was listed on the tombstone.

Information