Explosion in the sky

The cold war was waning. It seemed that the United States and the Soviet Union were ready to discuss their differences. Suddenly, Soviet fighters shot down a Korean civilian airliner. What was it - a mistake, a provocation, or the logical conclusion of a paranoid policy?

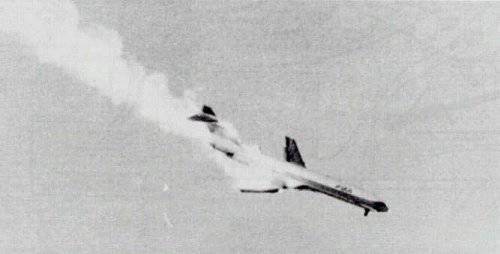

Now I'll try with a rocket, - a calm voice sounded through the interference of the radio. - I'm approaching the target ... I launched. Target destroyed. At 6.47 am on September 1, 1983, the pilot of the Soviet supersonic Su-15 fighter made sure that the target was hit: the Boeing 747-200B began to descend in a spiral towards the icy waters of the Sea of Japan. The hunter hit his prey with two armory systems - a thermal missile that disabled the engine, and a radar homing missile that probably hit the fuselage. "Korian Air 007 ..." - the pilot of the airliner managed to shout out into the radio. Then silence. Within 14 minutes, the huge plane fell from a height of 11 meters into the sea, west of the Russian military bases on Sakhalin Island. Nearby Japanese fishermen smelled burning fuel. There were 000 civilians and crew members on board.

Pangs of uncertainty

Was "KAL-007" hijacked? Has there been an accident? For 18 hours, hope gave way to horror, as there was no official clarification about the missing liner. No one received an SOS signal from his commander. The Japanese air traffic controllers apparently did not notice that their radars were showing the aircraft seriously off course. The pilot of another South Korean aircraft, which was in the air at a distance of 160 kilometers from the airliner, could not contact the commander of the ship, Chon, but did not consider it necessary to raise the alarm. Finally, US Secretary of State George Shultz stunned the world by announcing what US intelligence experts had learned from analyzing computer generated information: KAL-007 had been shot down mid-air by the Soviet military. “People around the world are shocked by this incident,” said President Ronald Reagan. One US congressman said, "Attacking an unarmed civilian aircraft is like attacking a school bus." For two days, representatives of the Soviet Union made literally no comments. The USSR then issued a statement regarding an "unidentified aircraft" that "grossly violated the state border and entered deep into the airspace of the Soviet Union." TASS claimed that the fighter-interceptors only fired warning shots with tracer rounds. There were also hints in the statement that the flight was carried out under the direction of the Americans for espionage purposes. Passions in the international arena ran high. "Civilized countries do not recognize diversion as a capital crime," raged Jean Kirkpatrick, US Representative to the United Nations. The delegates, numb with horror, listened to a tape recording of the Soviet pilot's radio communications. Obtained from the Japan National Defense Administration, the film proved that the plane had been shot down in cold blood. The reaction of Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko was belligerent: “Soviet territory, the borders of the Soviet Union, are sacred. Regardless of who resorts to provocations of this kind, he must know that he will bear the full brunt of responsibility for such actions.

The hunt for the black box

Both the Russians and the Americans immediately rushed to look for the so-called "black box", which contains records of flight parameters and crew conversations. The battery-operated "black box" radio beacon, although designed to transmit a signal even from a depth of 6000 meters, would be discharged in a maximum of a month. With a fully charged battery, it could be heard from anywhere within a five-mile radius. In that hectic atmosphere, according to reports from the American aircraft carrier Sturtet, it was only by pure chance that a collision of ships on the high seas west of Sakhalin was avoided. All efforts were in vain: the “black box” was never found. Instead, the cruel sea returned only pieces of metal, personal items and scattered human remains that could not be identified. Despite the harsh weather conditions and the great depth of the ocean gorges, the search engines continued to work until November 7th. The truth was to be established using computer recordings and data from the last hours of the KAL-007 flight, obtained with the help of top secret equipment and intelligence observers.

American spies?

Eight days after the plane crash, Chief of the General Staff Nikolai Ogarkov spoke on television with a new version. By implicitly admitting that Soviet fighters "stopped" the airliner with two air-to-air missiles, he presented two conflicting excuses. On the one hand, he claimed that the Soviet ground surveillance services had confused KAL-007 with an American spy plane in the same area. On the other hand, he accused the Korean airliner of being involved in spying for the United States. The purely military decision to destroy the passenger airliner was made by the commander of the Far Eastern Military District, and not by the top military or civilian leadership, as Ogarkov explained. Western observers ridiculed both statements. Indeed, an American RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft two hours before the missile attack passed 145 kilometers from KAL-007, flying in the opposite direction. According to the records, a Soviet fighter pilot observed a Korean airliner that is one and a half times the size of an RC-135. He twice reported seeing navigation and flashing lights. As for the accusation of espionage, there are several curious circumstances. The commander of the ship, Chong, tried to get his airliner off course over a very secret area. A naval center and six air bases were located on Sakhalin Island, which were extremely important. Test launches of intercontinental ballistic missiles were carried out on the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was a vital line of Soviet defense. In the Sea of Okhotsk, which stretched between them, nuclear submarines cruised, whose missiles were directed at targets in the United States. Nevertheless, experts believed that there was no need to endanger the lives of civilians by carrying out a covert intelligence operation. The Boeing 747, flying at high altitude at night, could not gather any information about anything. South Korean President Chung Doo-hwan irritably dismissed Marshal Ogarkov's explanation: "No one in the world, except the Soviet authorities, would believe that a 70-year-old man or a four-year-old child would be allowed to fly on a civilian aircraft whose task was to violate Soviet airspace for espionage purposes." .

Unexplained deviation

Why, then, did an experienced pilot, using the most modern equipment, deviate so far into the depths of Soviet territory? All three "inertial navigation systems" (INS) installed on the Korean aircraft included gyroscopes and accelerometers, which were supposed to guide the aircraft along a predetermined route. For greater accuracy, all three computers worked autonomously, receiving information independently of each other. Did it happen that the wrong coordinates were entered into all three computers? Is it possible that the crew neglected to check the INS coordinates with the coordinates on the flight charts, as is usually done? Could an experienced pilot forget to check if the actual position of the aircraft matches the waypoints marked by the INS during the flight? Commander Chon, in his last radio contact with Tokyo, confidently reported that he was 181 kilometers southeast of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. In fact, he was exactly 181 kilometers north of the island. Why didn't the air traffic controllers inform him of the error? Could he purposefully fly over the closed Soviet territory in order to reduce the consumption of expensive fuel for his economical owners? He was already flying the Romeo 20 route, which was close to Soviet territory: the pilots usually used weather radar to make sure they didn't cross the border. By changing the route, the pilot would put the plane in danger, and would not save much money. Documents show that never before during a regular flight did the aircraft deviate from the approved flight plan. In addition, the South Koreans knew better than anyone about the risk associated with a deviation from the course. In 1978, the Russians had already fired on another stray Korean airliner and forced it to land. The Boeing 707 hit by a thermal missile lost control and descended almost 10 meters before it was able to level out and make an emergency landing in the Arctic Circle, on a frozen lake near Murmansk. Two passengers died. The Russians rescued the survivors, including 000 wounded, and then billed the South Korean government for the services - $13.

Hasty evaluation?

This incident sowed suspicion in the minds of the Russians, who were deeply concerned that a Korean Boeing 707 had slipped into their airspace unnoticed. This time they tracked the KAL-007 radar image for about two and a half hours as it flew along the border. As soon as the airliner crossed the eastern border of the Kamchatka Peninsula, four aircraft, a MiG-23 and a Su-15, hurried to meet the intruder, although only two pilots' conversations were recorded. Four more interceptors joined the chase later. One danger threatened the interceptor pilots - lack of fuel. All aircraft could stay in the air for just under an hour, even with extra tanks. Pilot number 805, who fired the fatal rocket salvo, dropped his empty tanks seconds after the KAL-007 sighting. He had only 35 minutes to complete the task and return safely to base. Flying in from behind and locking on to an unsuspecting target, the 805 transmitted an "friend or foe" (IFF) signal to the airliner in order to identify it. However, only a Soviet aircraft would have been able to receive this signal on the frequency used by the fighter. The pilot of the 805 said he saw the flashing lights of the Korean airliner flashing. The pilot of one of the MiG-11s, who was about 23 kilometers away, reported that he could see both the interceptor and its target. According to Western experts, visibility above 10 meters should have been good that night. Moreover, Soviet pilots, as well as pilots from the United States and other Western countries, are required to be able to distinguish the silhouettes of aircraft. The humpbacked Boeing 000, which is called the "eggplant", cannot be confused with anything. A white-painted jet liner flew over the clouds, illuminated by a crescent moon. In addition, intelligence experts agree that the operators of Soviet radar stations keep a log, which contains information about all commercial flights whose routes pass near the border. Then the pilot of the 747th claimed that he allegedly fired 805 warning shots with tracer rounds. The tape recording his talks does not confirm this version. As soon as the KAL-120 reached the point from which 007 seconds of summer remained to international airspace - about 90 kilometers - the Su-19, whose fuel tanks were emptying at a terrifying speed, fired a volley and only briefly lingered to see the results .

Mysterious Consequences

Despite the formidable accusations and counter-accusations of diplomats and politicians, no one wanted the incident to escalate into a confrontation between the great powers. President Reagan spoke of a "crime against humanity," but the United States' responses, such as asking other countries to stop air travel from the Soviet Union for two months, were measured. 11 Western states have agreed to not so long-term sanctions. The death of innocent civilians was a tragedy, but the world community seemed to agree that revenge or punishment should not stand in the way of a relationship that could save millions of lives. Even the publication of the facts about the destruction of KAL-007 did not prevent the Soviet and American representatives in Geneva from continuing active negotiations on a draft agreement on nuclear weapons. According to Reagan, the US approach was to "demonstrate resentment while continuing negotiations." The specialists did not seek revenge, but wanted to solve the riddle. Could such a terrible navigational error happen again? Investigations, studies and speculation have come to nothing. However, as a result of calculations performed after simulating flight conditions on a Boeing mechanical test bench at the Seattle plant, one rather convincing explanation was proposed. As Commander Jeon took off from Anchorage, he was unable to check his pre-programmed flight path with the INS system because the Alaska airport's high-frequency radio beacon was temporarily turned off for maintenance. Relying on his compass during takeoff, the pilot set a heading of 246 along it. The deviation from the prescribed route of Romeo-20 in this case would be only 9 ° according to the compass. If the crew commander continued on this course and did not switch to the INS, his mistake, coupled with the wind speed in the upper atmosphere, could bring the KAL-007 directly under the missiles of the vigilant Soviet interceptor fighters. Could an electrical problem on board an airliner have paralyzed it, completely knocking out vital navigation systems, lights, and radio transmitters? The likelihood of such a development of events is extremely small. Each of the three blocks of the INS had an autonomous power supply. The lights could be kept running by any of four electrical generators, one for each aircraft jet engine. Until the fatal explosion, the crew did not lose contact with ground tracking stations located along the route for a minute.

Human tragedy on the global stage

- Nothing special, the most ordinary flight. It was a very, very calm flight, - recalled the steward responsible for the economic part of the first stage of the KAL-007 flight. Indeed, with the exception of one US congressman flying alone in first class, the rest of the passengers were ordinary citizens. Many flew with entire families. Most of the passengers spent their time in the same way - whiled away the weary hours of sleep in the dimly lit cabin. Everything was as usual. Many commercial flights followed the KAL-007 route every month. Because of this ordinariness, it was even harder for relatives and friends to endure grief. From Korea, the grieving relatives were taken to Hokkaido and put on ferries that took them to the waters where the body of a child, one of the passengers on that flight, was found. In memory of all the dead, wreaths and bouquets of fresh flowers were lowered into the water.

Information