The problem of drunkenness in Soviet Russia of the 20s of the last century and the formation of a "drunken budget" (part two)

(1 Corinthians 6: 10)

The release of 40 ° vodka had a very positive effect on the drug situation (the wedge was kicked out with a wedge), and it was initiated by the Decree of the USSR SNK on 28 in August 1925, “On the introduction of the provisions on the production of alcohol and alcoholic beverages and trade in them”, which allowed trade in vodka. October 5 1925 was introduced wine monopoly [1]. Evaluating this event in the culturological perspective, one can say that these decrees symbolized the final transition to a peaceful - stable life, since in the public consciousness of Russia, restrictions on the admission to the use of spirits were consistently tied to social upheavals.

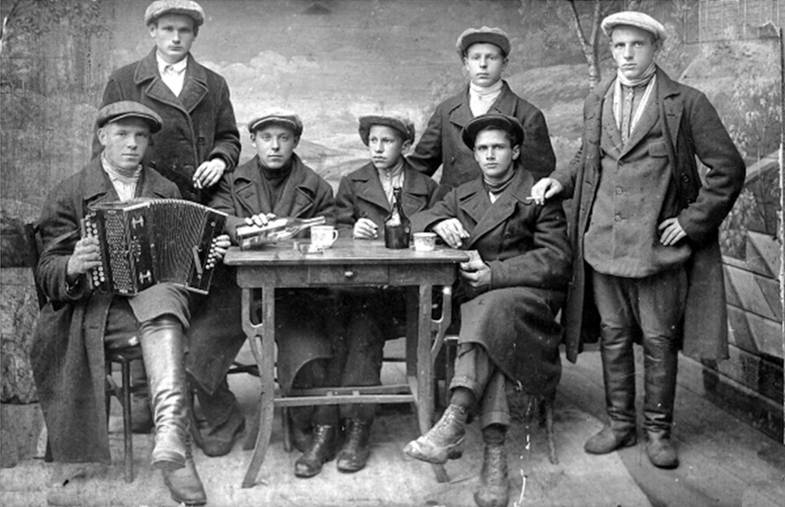

Accordion and bottle: cultural leisure.

New Soviet vodka began to be called "rykovka" in honor of the chairman of the USSR SNK N.I. Rykov, who signed the above decree on the production and sale of vodka. In the midst of the intelligentsia in the middle of 1920-s, there was even a joke that everyone in the Kremlin plays his favorite cards: Stalin has “kings”, Krupskaya plays “Akulka”, well, and Rykov - of course, “drunkard ". It is noteworthy that the new Soviet packaging of alcohol received a peculiar kind of playful, but very politicized names among the people. So, a bottle of 0,1 l. called pioneer, 0,25 l. - Komsomol, and 0,5 l. - party member [2] .104 At the same time, according to the memoirs of Penzents - contemporaries of the events, they used the same, pre-revolutionary names: sorokovka, rogue, bastard.

Vodka launched on sale in October 1925, at the price of 1 rubles. for 0,5 l., which led to a huge increase in the volume of its sales in the Soviet cities [3] .106 Nevertheless, the moonshine did not drink less. In any case, in the Penza region. By approximate calculations, in 1927, in Penza, every working worker (data are given without gender and age differentiation) used 6,72 bottles of moonshine, and, for example, every working employee - 2,76 bottles [4] .145 And this is generally, and only for men of mature age, this number should be increased even in 2-3 times [5].

The reason why people liked moonshine was not only in its cheapness compared to state vodka. When consumed, the moonshine gave the impression of increased strength from the harsh and highly active impurities contained in it (fusel oils, aldehydes, esters, acids, etc.), which could not be separated from the alcohol during the artisanal conduct. Laboratory studies conducted in the second half of 1920-s showed that these impurities were contained in moonshine several times more than even in crude factory alcohol, the so-called “sivukha”, which was withdrawn from sale due to its toxicity under the tsarist government. So all the talk about moonshine, "clean as a tear," is a myth. Well, now they drank it, and is it necessary to talk about the grave consequences of poisoning with such “drinks”? These are debility children [6], and delirium tremens, and fast-developing alcoholism.

Interestingly, the price of vodka was continuously increasing: from 15 in November 1928 to 9%, and from 15 in February to 1929 on 20%. At the same time, the price of wine was on average higher than vodka at 18 - 19% [7], that is, wine could not replace vodka in price terms. Accordingly, the number of shreds immediately began to grow. Increased production of moonshine. That is, those successes that were achieved by the release of state vodka were lost with an increase in its sale price!

Everyone actively drank — the Nemans, the workers, the Chekists, the military, about which the Penza Sponge RCP (B) [8] was regularly informed. It was reported: “Drunkenness among printers has become firmly established in their life and is chronic” [9], “In the cloth factory“ Creator Worker ”, the total drunkenness of workers from 14-15 years”, “Indulgent drunkenness at the glass factory No. 1“ Red Giant ”and t .d [10]. 50% of working youth saw regularly [11]. Absenteeism exceeded the pre-war level [12] and, as noted, there was one reason - drunkenness.

But all this pales in front of data on alcohol consumption (in terms of pure alcohol) in families. If we take the consumed alcohol per family as 100%, then we get the following increase in family alcohol consumption: 1924g. - 100%, 1925. - 300%, 1926. - 444%, 1927. - 600%, 1928. - 800% [13].

How did the top of the Bolshevik party feel about drunkenness? It was declared a relic of capitalism, a social disease that develops on the basis of social injustice. The second program of the RCP (b) ranked it along with tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases as “social diseases” [14]. In this regard, the attitude of V.I. Lenin. According to the memoirs of K. Zetkin, he quite seriously believed that “the proletariat is an ascending class ... does not need intoxication that would stun it or excite it” [15]. In May 1921 of the year at the 10 All-Russian Conference of the RCP (b) V.I. Lenin declared that “... unlike the capitalist countries that use such things as vodka and other dope, we will not allow this, no matter how profitable they are for trade, but they lead us back to capitalism .. . "[16]. True, not everyone surrounded by the leader shared his sober enthusiasm. Here, for example, that V.I. Lenin wrote G.K. Ordzhonikidze: “I received a message that you and the 14 commander (the army commander of 14 was IP Uborevich) drank and walked with women for a week. Scandal and shame! ”[17].

Not without reason, the decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars, adopted in May 1918 of the year, for moonsharing provided for criminal responsibility in the form of imprisonment for at least 10 years with confiscation of property. That is, it was attributed to the most dangerous violations of socialist legality. But how many were put on 10 years? In Penza, on 5, one (!) Employee of Sponge (well, of course!) Is [18], but no more. The rest got off with a fine and monthly (2-6 months) terms of imprisonment, and public censure was announced to others and ... everything! Later, namely in 1924, it was noted: “The issue of secret distillation is catastrophic ... when examining cases, we must remember that our government is not at all interested in having 70-80% of the population among us as indictable” [19]. That's even like - 70-80%! And it was noted not by anyone, but by the Penza provincial prosecutor!

Interestingly, the class approach was also present in relation to those fined for moonsharing. According to the Penza District Prosecutor's Office from 9 in December 1929, the average amount of the fine for moonshine was: for a fist - 14 rubles, for the middle peasant - 6 rubles, for the poor man - 1 rubles. Accordingly, the worker paid 5 rubles, but nepman paid 300! [20]

As a result, “bottom-up” appeals went that the best way to combat moonshine is to produce state vodka. And ... the good of Lenin was no longer there, the voice of the people was heard. Began to make "rykovka." But the “fight against drunkenness” also has not been canceled. Alcohol production increased, but, on the other hand, its growth caused serious concern to the party and the executive branch. As a result, in June 1926, the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) issued the theses "On the fight against drunkenness." The compulsory treatment of chronic alcoholics and the fight against home brewing was recognized as the main measures in the fight against it. In September 1926 of the year issued a decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR "On the immediate measures in the field of medical, preventive and cultural-educational work with alcoholism." He envisaged the deployment of the fight against home brewing, the development of anti-alcohol propaganda, the introduction of the system of compulsory treatment of alcoholics [21].

The Society for the Fight against Alcoholism was created, its cells began to be created all over the country, the pioneers began to fight For a Sober Daddy, on the initiative of the Penza Society in the newspaper Trudovaya Pravda in 1929, in each issue a black list was published - F .AND ABOUT. and the workplace of people detained by the police in a drunken state. But it helped a little. The townspeople did not pay attention to these lists.

As regards I.V. Stalin, he initially supported the activities of this society. He was well aware of the situation in the field of alcohol consumption and was aware of the extent and consequences of alcoholization of the population of the country of the Soviets [22]. Therefore, it is no coincidence that E.M. Yaroslavsky, N.I. Podvoisky and S.M. Budyonny. However, when industrialization required additional funds, and the army reform required it, he very quickly chose the least of two evils. The situation became critical in 1930, and it was then that Stalin, in a letter to Molotov on September 1, 1930, wrote the following: “Where to get the money from? It is necessary, in my opinion, to increase (as much as possible) the production of vodka. It is necessary to discard the previous shame and directly, openly go to the maximum increase in vodka production with a view to ensuring real and serious defense of the country ... Keep in mind that the serious development of civil aviation it will also require a lot of money, which again will have to appeal to vodka. ”

And the “old shame” was immediately dropped and practical actions were not long in coming. Already 15 September 1930, the Politburo made a decision: “In view of the apparent lack of vodka, both in cities and in the countryside, the growth in queues and speculation suggest that SNK USSR take the necessary measures to increase production of vodka as soon as possible. To impose on t. Rykov personal observation of the implementation of this decree. Adopt an alcohol release program in 90 million buckets in the 1930 / 31 year. ” Sale of alcohol could be limited only on the days of the revolutionary holidays, military gatherings, in stores near factories on the days of the issuance of wages. But these restrictions could not exceed two days per month [23]. Well, the anti-alcohol society was taken and abolished so that it would not get under our feet!

The conclusion is the author named in the first part of this research material, on which it is based, makes the following: “in the 1920-s. The twentieth century in Soviet cities widespread such a phenomenon as drunkenness. It captured not only the adult population, but also penetrated into the ranks of minors. Alcohol abuse led to deformation of family and industrial life, was closely associated with the growth of sexually transmitted diseases, prostitution, suicide and crime. This phenomenon was widely spread among the party members and Komsomol members. Especially widely drunkenness among urban residents spread in the second half of the 1920-ies. In terms of its scale and consequences, drunkenness among city dwellers, especially workers, assumed the character of a national disaster. The fight against him was inconsistent. Moreover, the country's needs for funds, which have increased in the era of accelerated modernization pursued by Stalin, did not leave in the minds of the leaders a place for “intelligentsia sentiments” about people's health. The drunken budget of the Soviet state became a reality, and the fight against drunkenness, including moonshine brewing, was lost, and it could not be won at all, and even more so under these conditions. ”

Links:

1. From stories combat drunkenness, alcoholism, moonshine in the Soviet state. Sat documents and materials. M., 1988. C.30-33.

2. Lebina N.B. "Everyday life of 1920-1930-ies:" Fighting the remnants of the past "... C.248.

3. GAPO F.R342. Op. 1.D.192. L.74.

4. GAPO F.R2.Opt.1. D.3856. L.16.

5. See. Shurygin I.I. difference in alcohol consumption between men and women // Sociological Journal. 1996. No.1-2. C.169-182.

6. Kovgankin B.S. Komsomol on the fight against drug addiction. M.-L. 1929. C.15.

7. Voronov D. Alcohol in modern life. C.49.

8. GAPO F.R2.Op. 4. D.227. L.18-19.

9.GAPO F. PNNUMX.Op.36. D.1. L.962.

10. Ibid. F.R2.Opt.4, D.224. L.551-552,740.

11. Young Communist. 1928, No. 4; News of the Komsomol Central Committee 1928. No.16. C.12.

12. GAPO F.R342. Op.1. D.1. L.193.

13. Larin Y. Alcoholism of industrial workers and the fight against it. M., 1929. C.7.

14. Eighth Congress of the CPSU (b). M., 1959. C.411.

15.Tsetkin K. Memories of Lenin. M., 1959. C.50.

16.Lenin V.I. PSS T.43. C.326.

17.Lenin V.I. Unknown documents. 1891-1922. M., 1999. C.317.

18. GAPO F.R2 Op.1. D.847. L.2-4; Op.4. D. 148. L.62.

19. Ibid. F. P463. Op.1. D.25. L.1; F. P342. Op.1 D.93. L.26.

20. Ibid. F. P424. Op.1. D.405. L.11.

21. SU RSFSR. 1926. # 57. Art. 447.

22. Help of the Information Department of the Central Committee of the RCP (b) I.V. Stalin // Historical Archives.2001. No.1. C.4-13.

23.GAPO F. Р1966. Op.1. D.3. L.145.

Information