How Brazil gained its independence

At the beginning of the 19th century, the once mighty Portugal was in a very difficult position. Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops invaded the country. In 1808, the royal family of Portugal was forced to leave Lisbon and cross the Atlantic to escape the possibility of being captured by the French. King Joan VI (1767-1826) settled in Rio de Janeiro. So Brazil at the time became the center of the Portuguese state, which contributed to the acceleration of its cultural and economic development. King Juan liked Brazil so much that when Napoleon was defeated, he still did not want to return to Lisbon. In 1815, Portugal was transformed into the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarve. This emphasized the new, higher status of the overseas colony.

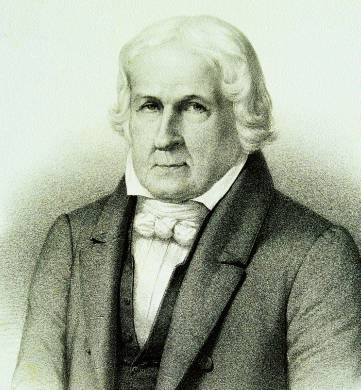

However, while King Juan was in Brazil, dramatic events took place in the metropolis. In August - September 1820 was a revolution in Lisbon, as a result of which the revolutionary junta that came to power adopted in January 1821 the constitution of the country. The constitution provided for the destruction of the Inquisition, the secularization of the lands of the Catholic Church, the abolition of the privileges of the feudal lords. King Juan, who returned to Lisbon in July of the same year, had no choice but to agree with the constitution. Returning to Europe, King João left his son Pedro (1798-1834) to rule Brazil and all the colonies of Portugal. Twenty-four-year-old Portuguese infant (pictured) lived almost his entire adult life in Brazil - he moved here with his parents in 1808, when he was only ten years old. The prince sympathized with the separatist sentiments of the Brazilian Creoles, who advocated disconnection from the metropolis. There were serious economic reasons for this - Brazil, as they say, tired of “feeding” Portugal. For centuries, Brazil remained the main source of resources for the Portuguese crown. In the end, the established political and economic elite of the colony began to realize that it could easily live without regular deductions to Lisbon. By the way, King Juan himself, leaving for Europe, recommended Infanta Pedro in every way to hinder Brazil from absorbing Portugal. According to the king, this could lead to the spread of revolutionary sentiments of the metropolis to Brazil.

However, while King Juan was in Brazil, dramatic events took place in the metropolis. In August - September 1820 was a revolution in Lisbon, as a result of which the revolutionary junta that came to power adopted in January 1821 the constitution of the country. The constitution provided for the destruction of the Inquisition, the secularization of the lands of the Catholic Church, the abolition of the privileges of the feudal lords. King Juan, who returned to Lisbon in July of the same year, had no choice but to agree with the constitution. Returning to Europe, King João left his son Pedro (1798-1834) to rule Brazil and all the colonies of Portugal. Twenty-four-year-old Portuguese infant (pictured) lived almost his entire adult life in Brazil - he moved here with his parents in 1808, when he was only ten years old. The prince sympathized with the separatist sentiments of the Brazilian Creoles, who advocated disconnection from the metropolis. There were serious economic reasons for this - Brazil, as they say, tired of “feeding” Portugal. For centuries, Brazil remained the main source of resources for the Portuguese crown. In the end, the established political and economic elite of the colony began to realize that it could easily live without regular deductions to Lisbon. By the way, King Juan himself, leaving for Europe, recommended Infanta Pedro in every way to hinder Brazil from absorbing Portugal. According to the king, this could lead to the spread of revolutionary sentiments of the metropolis to Brazil. However, in Brazil numerous units of Portuguese troops were stationed, whose command was against the independence of the colony. 5 June 1821 The commander of the garrison of Rio de Janeiro, General de Aviles, demanded that Prince Pedro remove Prime Minister Arcos, who spoke for the independence of Brazil. Two months later, the Portuguese parliament demanded Pedro to return to Lisbon. Infant brought this question to the public discussion. In all the cities of Brazil sent messengers instructed to find out the opinion of the population. The answer was clear - Prince Pedro must remain. 9 January 1822, Prince Pedro, uttered the historical phrase "Fico" - "I am staying." Since this time, 9 January is celebrated in Brazil as “Ficu Day”.

General di Avilesch, commanding Portuguese troops, hesitated. On the one hand, he was a categorical opponent of independence and should have prevented the separatists. On the other - Pedro was the heir to the Portuguese throne and the general simply could not afford to give the order to the troops to oppose the Infante. Delayed Avilesha took advantage of Pedro, who was supported by part of the loyal Brazilian troops. Pulling up loyal units, Pedro gave Avilesha and his soldiers the opportunity to embark on ships and sail to Portugal.

7 September 1822, Prince Pedro tore off the coat of arms of Portugal from his uniform and said: “With my blood, my honor and God, I will make Brazil free,” and then - “The time has come! Independence or death! We are separated from Portugal. ” So Brazil became an independent state. The words of Prince Pedro “Independence or death!” Became the official motto of the new country. A month later, on October 12, 1822, Prince Pedro was proclaimed Emperor of Brazil, and on December 1 was officially crowned to this position.

Emperor Pedro set about setting up a new state. The eminent intellectual José Bonifaciu de Andrada and Silva (1763-1838) was appointed the first Prime Minister of Brazil. He is called the true father of Brazilian nationalism and the ideologue of sovereign Brazil. Di Andrada and Silva was born in Brazil, that is, he was a Creole by birth. He received a good education at the famous university in Coimbra in Portugal, where he studied law and natural sciences, and then studied mining abroad. In 1800, di Andrada and Silva became the head of the geognosy department at the University of Coimbra, and also occupied the post of chief quartermaster of the mining department of Portugal.

In 1819, the scientist went to Brazil - he wanted to devote himself entirely to science, moving away from public affairs, especially since age was no longer young - 56 years. However, when the Portuguese parliament turned to Pedro, demanding the return to the metropolis, di Andrada and Silva in São Paulo led a movement that asked the regent, the prince, not to leave Brazil. 16 January 1822 de Andrada and Silva was appointed Minister of the Interior (in fact, Prime Minister of the country), but already on October 25 1822 the emperor dismissed him. But the Brazilians defended the scientist and after five days he was reinstated. However, 17 July 1823, he himself resigned, led the opposition, after which he was arrested and sent to Europe.

Thus, compared with the neighboring Spanish colonies, the proclamation of the independence of Brazil was virtually bloodless. General de Avilées’s Portuguese troops never entered into an armed confrontation with independence supporters. Moreover, the independence movement was headed not by anyone, but by the heir to the Portuguese throne, Prince Pedro. However, the painlessness of the declaration of independence did not mean that the young state had no opponents. The governors of the northern provinces of Bahia, Maranon and Para were loyal to the metropolis and opposed the declaration of independence. In addition, on the territory of these provinces, rather large Portuguese troops were stationed, which made Bahia, Maranon and Parus centers for possible opposition to Emperor Pedro. Given the huge distances and underdeveloped transport infrastructure, it was possible to send armed forces to the northern provinces to bring the governors to submission to the new emperor only by sea. And here the case played a role.

In mid-March 1823, Admiral Thomas Cochrane (1775-1860), a British naval officer and politician, came to Rio de Janeiro for business, a man of quite an adventurous warehouse, but with great naval experience. As far back as 1818, Cochrane, who had by then left the British naval service, was invited to Chile - to the post of commander of the Chilean fleet. In the shortest possible time, he was able to significantly strengthen the naval power of Chile and make several major victories over the Spanish fleet. Cochrane then went to service in Peru, where he also commanded the fleet and continued to trash the Spaniards.

While in Rio de Janeiro, the wandering admiral met with Emperor Pedro. He became interested in the idea of defending the independence of Brazil and entered the Brazilian imperial service as fleet commander. Before Cochrane was tasked to clear the coast of Brazil from the Portuguese ships. But it was very difficult to do that.

While in Rio de Janeiro, the wandering admiral met with Emperor Pedro. He became interested in the idea of defending the independence of Brazil and entered the Brazilian imperial service as fleet commander. Before Cochrane was tasked to clear the coast of Brazil from the Portuguese ships. But it was very difficult to do that. At the time of the events described, Emperor Pedro controlled only eight ships. Two ships could not go to sea, two more could play only auxiliary roles, another ship required repair. Thus, only three ships could go into battle. Portugal, on the coast of Brazil, had a battleship, five frigates, five corvettes, a schooner and a brig. But the superiority of the Portuguese naval forces was not a serious obstacle for the desperate Cochrane. The admiral ordered the Brazilian fleet to engage the Portuguese ships. But the crews of the Brazilian ships were almost unprepared, the sailors did not even have initial ideas about the service. As a result, Cochrane had to form the crew of his flagship of the American and British sailors, some of whom were in the Brazilian service.

In June, 1823, the flagship Pedro Primeiro, commanded by Admiral Cochrane, entered the bay of the port of Bahia. He suggested that the commander of the Portuguese garrison of Bahia, General Madeira, surrender in order to avoid civilian casualties. This requirement was reinforced by the fact that Brazilian ships blocked the port and the city began to experience food problems. However, General Madeira decided to evacuate the troops and inhabitants of Bahia on 70 transport ships, accompanied by 13 Portuguese warships. This entire fleet headed for San Luis di Maranon. However, the ships Cochrane managed to cause serious damage to the Portuguese. Moreover, Cochrane was able to approach the St. Luis de Maranyon 26 July - before the Portuguese, and informed the local governor that the Portuguese fleet was allegedly destroyed, and a huge Brazilian squadron would soon approach. The governor believed the tricks of the admiral and left at the head of the Portuguese garrison in the metropolis. So in the hands of Cochrane was the second most important center of opposition to Emperor Pedro. 12 August surrendered Pare - the third largest city, remained loyal to the metropolis. Thus, with the help of Admiral Cochrane, Emperor Pedro I established full control over the vast areas of northern Brazil.

Lisbon had no choice but to accept the loss of its largest and most important colony. 29 August 1825, mediated by the United Kingdom, Portugal recognized the independence of the Brazilian Empire. By the way, this recognition of sovereignty was not without direct cash payments - the secret addition to the contract provided for the payment of “compensation” in the amount of 600 thousand pounds sterling to Lisbon, as well as Brazil’s refusal of claims to the Portuguese colonies in Portugal and the preservation of trade privileges for Portugal in the Brazilian market. In addition, in the future, Brazil has pledged to ban the slave trade.

By this time, one of the most important items of income in Brazil was the cultivation of coffee for export. Coffee plantations were located in the south-east of the country, and their owners were the main lobbyists for the preservation of slavery and the slave trade in Brazil. Although the emperor Pedro I himself, as a man of fairly liberal views, called slavery a "Brazilian cancer", he was forced to put up with the position of influential latifundists. The planters who controlled the Brazilian parliament succeeded in reducing the number of Irish and German mercenaries from the ranks of the country's armed forces, since the latter had a negative attitude towards slavery. In the northeastern provinces where sugar cane and cotton were grown, they were unhappy with the dominance of the south. Northern planters blamed the southerners for overpricing slaves, and the government accused the southerners of patronage. As a result, in 1824, the northeastern provinces attempted to create an Equatorial Confederation and secede from Brazil, but the armed forces of the separatists were quickly neutralized by Admiral Cochrane’s fleet. Nevertheless, considerable tension in the country persisted, and it was connected, first of all, with significant internal contradictions - economic rivalry of the regions, confrontation between regional elites, who tried to lobby their own interests at the central level. The weakness of the central government of a young sovereign state was due, among other things, to an insignificant military budget. Despite the vast territories, Brazil had a very small regular army. The National Guard, which was formed on a territorial basis, in turn was a spokesman for the interests of regional elites and could not be regarded as a reliable pillar of the central government.

Nevertheless, almost the entire XIX century Brazil existed in the status of a constitutional monarchy - like the Brazilian Empire. In 1831, Emperor Pedro I was forced to abdicate in favor of his five year old son Pedro II. The reason for this was public dissatisfaction with the attempt of Pedro I to join the struggle for the Portuguese crown after the death of his father, King João. The Brazilians saw in this the possibility of reunification with the metropolis and suspected the emperor that he would again connect the two states. Three years after his abdication, in 1834, Pedro I died of tuberculosis. His son Pedro the Second (1825-1891) rules from 1831 to 1889 years. At first, his guardian was the same Jose Bonifaciu de Andrada and Silva.

In fact, it was during the reign of Pedro II that the final formation of Brazilian statehood took place. It must be said that it was associated with numerous wars and internal uprisings. The question of slavery was still acute. Pedro II himself was his opponent, but he did not dare to act radically, so as not to enter into conflict with large landowners - slave owners. Only in the 1888 year, already due to very serious protests, Princess Isabella, who replaced Father Pedro II, who was treated in Europe, signed the Golden Bull on the abolition of slavery. But this decision could not save the monarchy. 15 in November 1889 began an uprising in Rio de Janeiro, and on November 16 emperor Pedro II abdicated. Brazil was proclaimed a republic.

Today, Brazil is in fifth place among the countries of the world in terms of area and population. The country is developing rapidly both culturally and economically. Brazil plays an important role in Latin American and world politics, and in culture it is the de facto leader of the Portuguese-speaking world, beating in importance because of the size of the population of the former metropolis.

Information